Retrospective reassessments of some favourite albums from my record collection (in strictly chronological order).

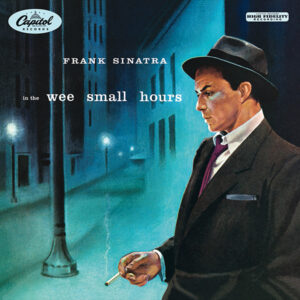

Frank Sinatra / In The Wee Small Hours

Frank Sinatra / In The Wee Small Hours

Capitol, 1955

Frank Sinatra’s ninth album, In The Wee Small Hours, isn’t quite the oldest record in my collection — I actually have ten other LPs from 1955, and seven others dating back even further (I think the oldest is the soundtrack to the 1950 Kirk Douglas movie, Young Man With A Horn). But in terms of industry history this might be the most significant, as it was the first “pop” album to be released on a 12” disc. That format had previously been reserved for classical recordings — considered by the labels to be more important and prestigious — but the success of this album helped render the 10” record obsolete. The new format’s microgrooves allowed for a longer running time, which in turn lent itself to a more conceptual approach. Rather than a grab-bag collection of songs or a package of previously-released singles, In The Wee Small Hours was compiled with a unifying theme in mind, making it perhaps the first ever concept album. That concept was clear from the artwork. Lonely and forlorn, Frank the jilted lover is resigned to wandering the streets after hours. This luckless romantic persona may seem cliched today, but at the time it was a departure for America’s most beloved entertainer. Aside from the brand new title track, the other fifteen songs were all standards, tastefully and sparely arranged by Nelson Riddle, making it one of the great late night listens. The album is said to have been inspired by the collapse of Sinatra’s tumultuous marriage to Ava Gardner, a union that deteriorated due to both parties’ frequent infidelities. Gardner also underwent two abortions while married to Sinatra, due to MGM’s strict penalty clauses preventing their stars from becoming pregnant. It was MGM that announced the couple’s separation in 1953, a few months after the release of From Here To Eternity, in which Sinatra had landed a role — revitalizing his career — thanks only to Gardner’s clout with the producers. She filed for a divorce in 1954, which was finalized in 1957. But the two remained friends, and in Gardner’s autobiography, published shortly after her death in 1990, she stated that Sinatra was the love of her life.

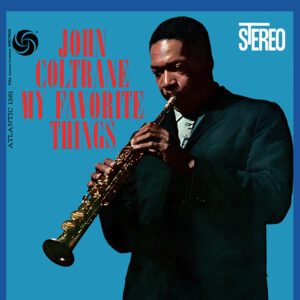

John Coltrane / My Favorite Things

John Coltrane / My Favorite Things

Atlantic, 1961

While not technically a Christmas album (side two includes “Summertime”), this is a record I play often around the holidays. Released in 1961, the LP takes its name from the title track, a modal rendition of the song from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The Sound of Music. At the time of recording the musical was just a year old, and though the lyrics make no mention of Christmas, the song quickly became something of a holiday standard. Coltrane’s version is a showcase for his new band and a preview of the innovative musical paths he would take in the sixties. McCoy Tyner’s piano prances over a simmering rhythm section comprised of Steve Davis on bass and Elvin Jones on drums, while Coltrane leads on a soprano sax whose sound is at once familiar and eerie. The key of E minor lends the material mystery and nuance — there are moments when the music takes on an almost byzantine quality. Even the song’s traditionally upbeat ending is left ambiguous and unresolved. Coltrane had only begun to play soprano the previous spring, after receiving the instrument as a gift from Miles Davis while on tour in Europe. After leaving Davis’ quintet, Coltrane formed his own quartet with whom he spent the summer playing Village sets and developing the sound that would be debuted on this album. Sessions took place over three days in October 1960 at Atlantic Studios at 1841 Broadway, and included Cole Porter’s “Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye,” plus fresh treatments of the popular Gershwin tunes “Summertime” and “But Not For Me.” But it’s the title track that has compelled me to return to this LP year after year, ever since I first heard it as a teenager. Clocking in at nearly fourteen minutes, “My Favorite Things” is a brooding, hypnotic masterpiece, and without doubt one of my favourite jazz recordings. There’s a line in the Elvis Costello song “This Is Hell” that goes, “My Favorite Things are playing again and again/But it’s by Julie Andrews and not by John Coltrane.” I always think of that whenever I give this record a spin. If you have this album (or failing that, a Spotify account) make sure to put it on this Christmas. I guarantee you won’t feel so bad.

Bob Dylan / The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan / The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

Columbia, 1963

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan was released just three days after the young artist had turned 22. Only 14 months had passed since the release of Dylan’s eponymous debut, but the distance between the two LPs is better measured in light years. Unlike its predecessor, Freewheelin’ was a record of all-original material, and established Dylan not only as the most exciting songwriter on the New York folk scene, but also a performer of a skill and intensity that belied his young age and boyish appearance. Drawing from current events for inspiration — as well as his romance with a young activist named Suze Rotolo — his subjects were both political and personal, his lyrics both scathing and absurdist. This recognition led to Dylan being lumbered with the unenviable label of “spokesman of a generation,” a tag he was keen to repudiate. His 2004 memoir, Chronicles, Vol. 1, recalls a headline from this period: “Spokesman Denies He’s A Spokesman.” Rotolo (and her very left-wing family) has often been credited with influencing Dylan’s more topical output. The couple had met at a folk concert at Riverside Church and had been living together (much to her family’s disapproval) in an apartment on West 4th Street for six months when (at her mother’s suggestion) Suze left to study art at the University of Perugia. She postponed her return several times, and this extended separation left Dylan pining: he wrote “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” upon learning she was considering staying in Italy indefinitely. Rotolo finally did return to New York in January 1963, and a few weeks later Columbia photographer Don Hunstein snapped her and Dylan arm in arm as they trudged through a snow-covered Jones Street, as part of a wider shoot around Greenwich Village. The image was used for the cover of Dylan’s upcoming LP which, along with Abbey Road, is probably the most replicated album photo of all time. Dylan and Rotolo broke up in 1964. For decades she refused to discuss their relationship, which continued to overshadow her own work as a visual artist, until 2008 when she published her own memoir called A Freewheelin’ Time. She died in 2011 aged 67.

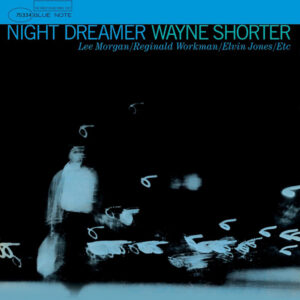

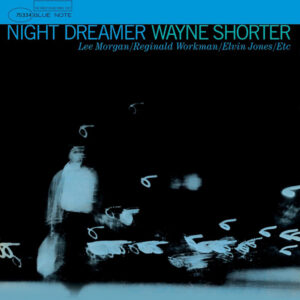

Wayne Shorter / Night Dreamer

Wayne Shorter / Night Dreamer

Blue Note, 1964

I recently conducted an inventory of my record collection and was slightly surprised to discover I have more LPs from 1964 than any other year (27). This is one of them. Released in November 1964, Night Dreamer was Wayne Shorter’s third album as a leader but his first for Blue Note. “This date came at a time as I was entering a new stage as a writer,” he said at the time. “And also, I knew that for my first album for Blue Note, I had to say something substantial!” The difference is notable not just musically, but visually: compare the front cover of this record with his previous one, Wayning Moments, on the Vee Jay label. The sleeve design was the unmistakable work of graphic artist Reid Miles, a Chicago native who was plucked from Esquire magazine in 1955 when Blue Note began producing 12” LPs. Miles soon developed a simple but unique style that made clever use of color, typography, and photography. Ironically, given that his bold artwork became a visual shorthand for the hard bop era, Miles didn’t particularly care for jazz, and relied solely on descriptions of the music from producer Alfred Lion. Most Blue Note sleeves in this period incorporated a cover photograph by label co-founder Francis Wolff. Typically, these were taken during recording sessions at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. Unusually, Night Dreamer uses an outtake from a nighttime location shoot with Shorter on 66th and Broadway. Like much of Manhattan, that area of the west side has changed a lot since 1964, but the huge sign on top of the Empire Hotel (the glow from which is visible in the background) is still there sixty years later. Around the time of this record’s release Shorter joined Miles Davis’ “Second Great Quintet,” but continued to turn out brilliant albums for Blue Note over the next few years, several of which — Juju, Speak No Evil, The All Seeing Eye — are filed after this one in my living room. In 2013 I was lucky enough to see Shorter perform a special concert to celebrate his 80th birthday, as part of that year’s jazz festival in Montreal. It remains the singularly most intense live music experience of my life.

Herbie Hancock / Empyrean Isles

Herbie Hancock / Empyrean Isles

Blue Note, 1964

Empyrean Isles was Herbie Hancock’s fourth release on the Blue Note label, but in abandoning some of the latin-soul explorations of his first albums for straightforward hard-bop, the 24-year-old established himself as one of the most inventive young musicians of his time, whose work from that point forward consistently challenged the conventions of jazz. At the time of this recording, three quarters of this young line-up had already been working in Miles Davis’ quintet; the sole horn player is Freddie Hubbard, who swaps his usual trumpet for a cornet. Drummer Tony Williams was just eighteen when these sessions took place on June 17, 1964. Hancock’s four tunes on this record are loosely themed around the myth of the titular islands, floridly described in the back cover liner notes by Nora Kelly. The most famous of these is “Cantaloupe Island” which, like Hancock’s previous fruit-inspired composition, “Watermelon Man,” soon became one of his signature numbers. The track gained a new generation of fans in 1993, when it was sampled by jazzy hip-hoppers Us3 for their hit, “Cantaloop (Flip Fantasia).”

John Coltrane / A Love Supreme

John Coltrane / A Love Supreme

Impulse, 1965

In 2011, on a cold January afternoon not unlike this one, I picked up this gently-used copy of A Love Supreme, John Coltrane’s 1965 masterpiece, for a mere three dollars at Big City Records, a second-hand LP store on East 12th Street specialising in soul, funk and jazz (don’t bother looking for it now — it closed in 2012). By that point I was already quite familiar with this landmark recording: I’d been gifted the CD one Christmas in the late nineties, and some time after that had read an entire book on the background and making of the album. Not even that book’s author, jazz historian Ashley Kahn, can pinpoint the precise date this record was released; some sources say January ’65, others suggest February of the same year. But after sixty years what difference do a few weeks make? The recording session took place on December 9, 1964 at Van Gelder Studios in New Jersey, where Coltrane led a quartet featuring pianist McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison on bass and Elvin Jones on drums. Though technically there are four tracks, the music is presented as a suite in four parts — “Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” “Psalm” — and to me it always felt more like a single piece, especially on CD. Given the record’s ambition and enduring impact, it’s surprisingly slight, clocking in at just under 33 minutes. This yearning, hypnotic record plundered new spiritual depths and obliterated jazz conventions of the time, taking listeners on a post-bop journey into the avant-garde. There are times when it barely resembles jazz at all — in fact, so meticulously was it composed, that it’s almost closer to a mini classical suite. Coltrane’s solo quest for enlightenment in the face of intense social upheaval continued in this direction until his death aged 40 in 1967. A Love Supreme was embraced by the counter-culture and is often cited as one of the most beloved and influential recordings of the sixties. Carlos Santana covered the first part of the record on his 1973 album Love Devotion Surrender; I saw him perform it on stage in Italy in 2004, which still ranks as one of the most memorable live experiences I’ve ever seen.

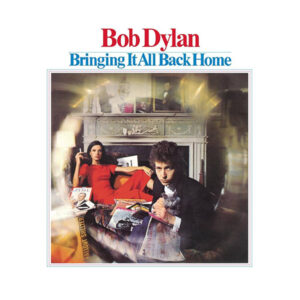

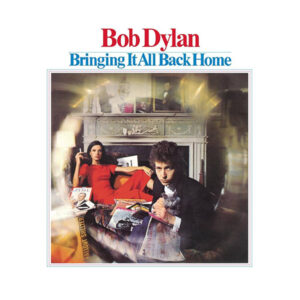

Bob Dylan / Bringing It All Back Home

Bob Dylan / Bringing It All Back Home

Columbia, 1965

The cover image for Bringing It All Back Home, Bob Dylan’s fifth album, was shot by Daniel Kramer at the home of Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman, near Woodstock. Dylan perches on the end of a chaise longue holding his cat (whose name was Rolling Stone) while languorous model Sally Grossman (Albert’s wife) stretches out behind him. Along with his new look — more wealthy upstate bohemian than beat troubadour — the style of Dylan’s lyrics was also shifting. Though the wit and wordplay remained, his imagery was becoming increasingly surreal, personal and complex. Side one of the record was also notable in that it featured a full band. This major turning point in the artist’s life has often been described as an abandonment of his folk origins, but Dylan was never really a folk singer. He was embraced and championed by the folk community because they saw in him what they wanted to see, but for Dylan, that Village scene was merely a step in his rapid evolution. Regardless of his sound, in appearance and attitude Dylan was always a pop singer and a pop star in the truest sense, as evidenced by D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary film from this period, Dont Look Back. Side two was mainly acoustic, but this wasn’t enough to appease a minority of dissenters. This situation culminated four months later at the Newport Folk Festival, where factions of the crowd revolted against Dylan’s electric performance. Ironically, the song that sparked reaction from the crowd was “Maggie’s Farm,” a blatant gripe against those seeking to curb his creative vision. This overblown incident entered rock folklore, and was dramatized in the recent Timothée Chalament movie, but for a more nuanced understanding of events, I’d recommend the 2005 Martin Scorsese documentary, No Direction Home.

The Beatles / Let It Be

The Beatles / Let It Be

Apple, 1970

This afternoon I finally got around to finishing Get Back, Peter Jackson’s epic three-part Beatles documentary. The series meticulously chronicles sessions for the band’s next album (eventually released in 1970 as Let It Be) and aborted TV special, before culminating in the surprise performance on the rooftop of Apple Studios on 30th January 1969 (I always remember the date because it was ten years to the day before I was born). Edited from 60 hours of film footage and over 150 hours of audio material originally intended for Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s film (also entitled Let It Be), Jackson’s project was conceived as a standalone feature with a theatrical release, but Covid delays and pandemic viewing trends prompted Disney to re-purpose it into a binge-worthy streaming event. Now, nobody loves a rockumentary more than me, and the prospect of indulging in hours of unseen Fab Four footage filled me with glee. Yet even this Beatle obsessive found the experience of watching the series less than riveting at times, mainly because of the bloated format. The suggestion of urgency through on-screen captions and calendar graphics seems like an afterthought designed to mask the lack of a narrative structure. During a debate in the third episode Lindsay-Hogg comes to the discovery that he’s spent three weeks shooting footage but still has no story, a problem neither he nor Jackson quite managed to overcome. Naturally, there are moments both priceless and hilarious, but rarely are these genuinely revealing and they mostly fail to convey the individual band members in any new light. But the documentary is utterly absorbing as a window into a hyper-specific place and time, capturing the detailed dynamics of the group and their nebulous inner circle, while hinting at the band’s impending and unavoidable dissolution. Anyway, the series compelled me to revisit Let It Be, an oft-maligned album and maybe the Beatles LP I’m least fond of. The record confirms what the documentary shows, which is that Paul was really the only creative Beatle still fully on board by this point (the most realised compositions are all McCartney’s). But at least it clocks in at a brisk thirty-five minutes…

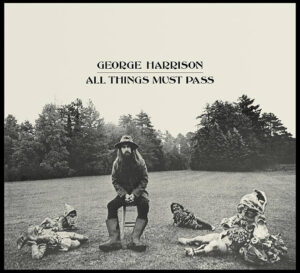

George Harrison / All Things Must Pass

George Harrison / All Things Must Pass

Apple, 1970

George Harrison’s epic solo debut arrived just seven months after the Beatles’ split, and only six after the release of the band’s final LP, Let It Be. Harrison, always “the quiet one,“ had emerged as an able songwriter, but remained a victim of band inequality: typically he only saw one of his compositions on each side of a Beatles release. After the break-up he found himself sitting on dozens of unreleased songs, some of which dated back to 1966 and had already been overlooked by Lennon and McCartney. There was enough material for several albums, but for commercial reasons the recordings were contained onto an eighteen-track, double LP, which also included a bonus disc of somewhat indulgent studio outtakes entitled “Apple Jam.” The whole thing came packaged in a large box, the kind typically used for operas, which wasn’t wholly inappropriate: many have described the record as sounding “Wagnerian” in its scope and bluster. Much of this sonic grandeur was the influence of Phil Spector, who initially acted as producer on the sessions before removing himself from the project due to “health reasons” (Harrison once said Spector needed “eighteen cherry brandies” before he could start work). Spector’s trademark “Wall of Sound” technique is evidenced throughout the album’s four sides even though Harrison completed production duties himself — he later admitted he got carried away with excessive multi-track layering and heavy reverb overdubs. In that sense the album is perhaps a harbinger for some of the bloated, grandiose albums that would come to define a lot of rock music in the seventies. Stunning for its musical variety and emotional range, the record is both a celebration of Harrison’s creative individuality and an emphatic liberation from the highly rewarding yet spiritually stifling phenomenon that was Beatlemania. Even the cover art, featuring four broken gnomes, was designed to indicate the end of that particular and unrepeatable era. I think this album is best enjoyed in its entirety on an autumn afternoon with a cup of tea.

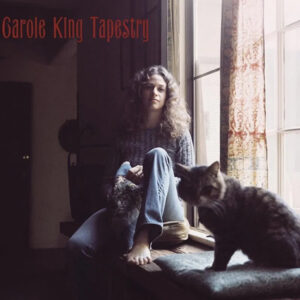

Carole King / Tapestry

Carole King / Tapestry

Ode, 1971

While making coffee this morning I put on Carole King’s second solo album, Tapestry, for the first time in years. Aside from the quality of her songs I always liked King’s voice, straight and unadorned. Her earnest sound — and relatable look — pioneered a quintessentially New York brand of feminist ethnic soul which could not have emerged from any other city (see also Laura Nyro). By the late sixties King had left for California (the first track describes a romantic infatuation in terms of an earthquake) but this album still exudes an East Coast urgency. It’s pitched somewhere between the Brill Building and Laurel Canyon, weaving the sophisticated piano-led pop hooks of one with the personal introspection and intimacy of the other. Tapestry was recorded in the same studio and at the same time as Mud Slide Slim by James Taylor — inevitably the two albums share much of the same personnel and even a song. In one of my previous design studio jobs one of our clients was named Carol King (without the E) and so every time we visited her office the “You’ve Got A Friend” jokes would fly. Two other songs on Tapestry had already been hits for the Shirelles and Aretha Franklin, but with the exception of “Smackwater Jack” (which probably sounded dated even in 1971), every track has a sort of timeless purity, as all great pop songs tend to do. It’s also my favourite album with a cat on the cover, though to be honest I can’t think of many others.

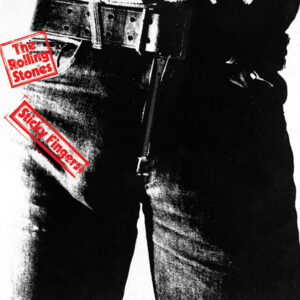

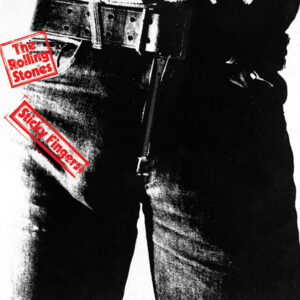

The Rolling Stones / Sticky Fingers

The Rolling Stones / Sticky Fingers

Rolling Stones Records, 1971

Sticky Fingers was the Rolling Stones’ first studio album of the seventies, the first since Altamont, the first without founding member Brian Jones, and the first to showcase the talents of new lead guitarist Mick Taylor. But perhaps most significantly, it was also the first release on the band’s new label, Rolling Stones Records. Like the Beatles, the Stones had fallen victim to Allen Klein’s financial (mis)management and dubious contracts, and were thus compelled to form their own company to control their recordings and publishing rights. Mick Jagger (always the most image-savvy Stone) commissioned John Pasche, a British junior art director working at the New York advertising agency of Benton & Bowles, to create a logo for the eponymous brand. The idea for the now ubiquitous “tongue and lips” design came about after Jagger spotted an image of the Hindu goddess Kali inside a corner shop. For the album artwork, Pasche’s logo was modified by Craig Braun and included on the inner sleeve and centre labels of the LP. The cover concept was devised by Andy Warhol, whose Coronet signature can be seen on the pair of white briefs visible behind the working zipper. The identity of the crotch on the cover has never been confirmed, but it is assumed to be either a lover of Warhol’s or else a member of his Factory circle. Later releases of the album dispensed entirely with the zipper gimmick, which proved costly to manufacture and also tended to damage the vinyl itself during transit. I have an American version; my parents’ British copy has a different type treatment on the cover. Due to the censorship of the Franco era, in Spain the cover was replaced by a more literal (and disturbing) image of a pair of fingers emerging from a tin of treacle. The iconic logo has now appeared on every Rolling Stones release for half a century, not to mention countless items of merchandise. Pasche received £50 for his design upon completion, and a further £200 in 1972, before selling his copyright to the Stones for a much higher sum in 1984. His original artwork now belongs to the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Marvin Gaye / What’s Going On

Marvin Gaye / What’s Going On

Motown, 1971

Perhaps more than any other, Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On is the record that altered soul music’s course, and one that even half a century later still resonates on every level. At first listen, the album is a reaction to the all too familiar struggles affecting Black America, but it was also fueled by Gaye’s personal depression, brought on by the collapse of his marriage, cocaine addiction, and the death of his singing partner, Tammi Terrell. Gaye had scored seven top forty hits with Terrell before she was diagnosed with a brain tumor; she died in 1970 aged just twenty-four. Though Gaye was a commercial certainty, for the hit-making factory that was the Tamla label the record represented a risky departure, as the smoothest singer in their stable now embarked on what was essentially a protest album. Gaye’s mood of disillusionment is apparent immediately on the record’s iconic cover. Gone is the smiling, clean-cut young man to whom millions had become acquainted. Instead a bearded Gaye appears by a deserted set of swings, weary and lost in thought, seemingly indifferent to the rain that drenches him. Side one begins with snippets of street chatter before the opening saxophone bounces in like a mellow breeze, belying the despairing lyrics of the title track. The record continues in this vein, with each song flowing into the next to create a slightly eerie, almost dreamlike suite whose singular collective tone helped define the sound of progressive soul in the early 1970s. What’s Going On may represent the first major personal statement by a Black solo pop artist, and subsequent albums by Gaye’s contemporaries — Stevie Wonder, Isaac Hayes, Curtis Mayfield — began to lean in similarly socially-conscious directions. Despite Motown founder Berry Gordy’s initial concerns, the record peaked at number six, charting again after Gaye’s death in 1984. In 2020 Rolling Stone magazine placed What’s Going On at number one in its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time. Though such accolades are purely futile and entirely subjective, such recognition is testament to the music’s quality and also a timely reminder, were it needed, that the record’s message is no less urgent or relevant today.

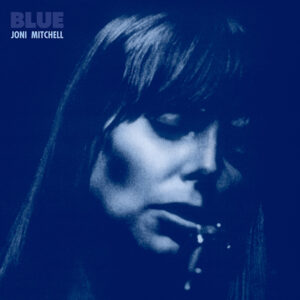

Joni Mitchell / Blue

Joni Mitchell / Blue

Reprise, 1971

Blue was the first Joni Mitchell album I ever heard, but such was its status as a defining artifact of the seventies (not to mention its iconic cover art) I was aware of it before I’d ever put it on. Though more rhythmic and varied than her previous records — Joni accompanies herself on most tracks with guitar, piano or Appalachian dulcimer — Blue is still relatively spare compared to the lush jazz-rock arrangements of her mid-seventies albums. I always like to listen to it very loudly late at night, especially in summer. Blue was the record with which Joni’s star shifted from Canadian folk songstress and would-be painter to international rock and roll icon, confirming her to be a musician, vocalist, songwriter and lyricist of singular style and talent. Poetic and almost painfully personal, the album made Mitchell the archetype of the confessional singer-songwriter that became inexorably associated with Southern California in the first half of the decade. The record is almost a concept album in that it traces an arc in the artist’s life in which Joni goes through two break-ups: her relationships with Graham Nash and James Taylor are said to have inspired half the songs on Blue (JT even shows up on guitar, though not on the tracks about him). Trading in Laurel Canyon domesticity she then takes us on several entertaining and evocative jaunts around Europe, a travelogue that’s both carefree and bittersweet, as Joni faces the necessary prospect of overcoming her own pessimistic worldview. Indeed, Blue introduced what would become a continuing theme in Mitchell’s work: travel, both real and metaphorical, as an essential tool for one’s own development and enlightenment. Side one’s opening line, “I am on a lonely road and I am traveling, traveling, traveling, traveling…” immediately explains her emotional state, but could also be an apt description for her entire career. Joni has spent a lifetime forging her own path in an industry that more readily celebrates mediocre men than brilliant women, and she has always seemed more than content to go it alone. Then again, who could keep up with her?

John Lennon / Imagine

John Lennon / Imagine

Apple, 1971

Unlike most records I’ve written about here, Imagine isn’t one I’m especially fond of. To me it is quite weighed down by a series of plodding mid-tempo numbers over which Lennon’s bitter rants do little but highlight his sour state of mind in the early seventies. Not that he didn’t have plenty reason to be angry: “Gimme Some Truth” is as lyrically relevant today as it ever was. But the infamous “How Do You Sleep?”, a five-and-a-half-minute diatribe against Paul McCartney, only reveals the gracelessness with which Lennon handled his lingering animosity towards his former songwriting partner after the pair’s acrimonious split. The song is only really interesting at this point for its hyper-specific lyrical content in the context of rock non-controversies. Other tracks seem ahead of their time. “I Don’t Want To Be A Soldier” is a loose, hypnotic jam that sounds more like 1991 than 1971. But “Crippled Inside” and “It’s So Hard” feel like folky (or jokey) genre exercises, while “Oh Yoko!” is an early example of Lennon’s gratuitous habit of laying down odes to his domestic bliss on wax. Lennon comes off better when he’s at his most vulnerable. The two ballads, “Jealous Guy” and “How?”, each showcase his talent for combining gorgeous melodies with raw moments of honest introspection. The same technique is of course used to greatest effect on the title cut. Inspired by Yoko Ono’s poem “Grapefruit” (a passage of which is reproduced on the record’s back cover), Lennon later theorized that the only reason the anti-religious, anti-nationalistic, anti-capitalistic anthem was so universally accepted was because it was “sugarcoated.” After all, it’s practically a socialist manifesto. The irony, of course, is that like other protest songs with a straightforward lyric, “Imagine” has been embraced most frequently and fervently by precisely the people towards whom its criticism is directed — politicians, corporations, churches, even celebrities — in other words, those with little imagination at all.

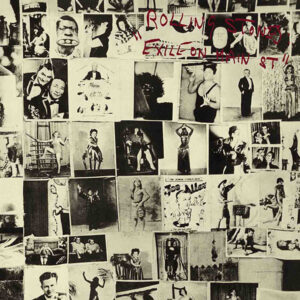

The Rolling Stones / Exile On Main St.

The Rolling Stones / Exile On Main St.

Rolling Stones Records, 1972

Exile on Main St. was the Rolling Stones’ tenth studio album, and is still considered by many to be their best work. High praise considering the bulk of the half-written tracks were captured by the band’s mobile recording truck during a loose series of nightly “sessions” in the damp and sprawling basement at Villa Nellcôte, a Belle Époque mansion on the Côte d’Azur that Keith Richards was renting having absconded (along with the rest of the Stones) to France to avoid paying British taxes (hence the album’s title). Built by an English banker in the 1890s, the property was said to have served as a Gestapo headquarters during the war — the arrival of the world’s most notorious rock and roll outlaws (and a revolving coterie of guests) only added insult to infamy. Overdubs were added later in Los Angeles, but most of the record’s sixteen original songs draw inspiration from the Stones’ hedonistic life on the road and substance-fueled escapades on the French Riviera. That said, Mick Jagger’s languid drawl is often buried so deep in the final mix that the vocals can feel fragmented or even unintelligible. One track, “Casino Boogie,” was actually composed by cutting up random phrases and assembling them into verses, a technique borrowed from William Burroughs. Another, “Sweet Black Angel,” about Angela Davis, is one of the few overtly political songs in the band’s entire catalogue. Musically speaking, no Stones release before or since is so heavily saturated by Mick and Keith’s adventures in (and fixation with) America’s deep south. The album is a murky, simmering stew of early rock and roll, blues, country, gospel and soul, but these songs aren’t mere genre exercises: there is a lived-in, hard-fought truth to them, that combined with a lyrical weariness makes for a record of rare (and raw) depth and honesty. Several numbers have since become part of the Stones’ live repertoire, but despite being a double LP the album didn’t produce the usual handful of hit singles. Though as my parents often recalled, “Tumbling Dice” received repeated punches on the jukebox at their wedding in August 1972.

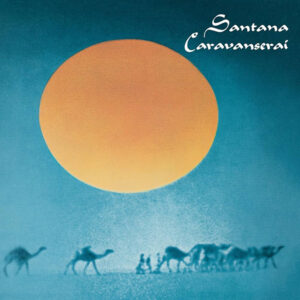

Santana / Caravanserai

Santana / Caravanserai

Columbia, 1972

Santana’s fourth album, Caravanserai, was released in October 1972. That same night the band performed at Spokane Coliseum, having just embarked on an epic world tour that would span five continents and last an entire year (the recording from the show in Fukuoka was released in Europe as the live triple LP, Lotus). In November 1973, my parents saw Santana at the start of their next tour at the Rainbow in London, a show I heard a lot about growing up (in 2004 I saw Santana with my parents in a piazza in Pistoia). Anyway, this was the album on which Santana broke free of the artistic restraints imposed by the narrow confines of commercially viable pop music. The result was a predominantly instrumental LP reflecting Carlos Santana’s blossoming interest in the spiritual jazz pioneered by Alice Coltrane and Pharaoh Sanders. Upon hearing the finished record, CBS executive Clive Davis accused Santana of committing “career suicide.” Indeed, Caravanserai produced no hit singles and only reached number 8 on the Billboard chart. But it’s my favourite Santana album up to that point precisely because it abandons any attempt to conform to radio or record company expectations. To me, some of Santana’s early hits feel firmly rooted in their era, while their English lyrics forced them towards “American rock band” territory, undermining their musical ambitions and spiritual worldliness. In every sense, Santana was always a band without borders, whose compositions and live performances transcended background or language. It’s no surprise that in 1986 the BBC chose nine-minute closer “Every Step Of The Way” for their closing World Cup montage (it’s on YouTube), acknowledging Santana’s Mexican roots while encapsulating the sun-drenched drama of that international event. I can’t talk about this album without mentioning “Song Of The Wind,” a genuine highlight and one of my mum’s all-time favourite tracks. Just as some of the band’s more conventional rock numbers haven’t aged well, this six-minute instrumental — while showcasing Santana’s effortlessly emotive guitar playing — is evidence that he could produce a work of timeless beauty simply by doing what came naturally.

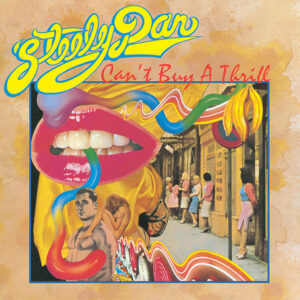

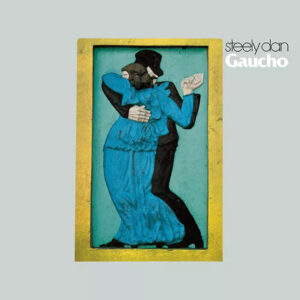

Steely Dan / Can’t Buy A Thrill

Steely Dan / Can’t Buy A Thrill

ABC, 1972

Can’t Buy A Thrill, Steely Dan’s debut album, was released in November 1972. I don’t know the exact date and it seems the internet doesn’t either. To recap: Walter Becker and Donald Fagen had met at Bard College in 1967, and were working in Los Angeles as staff songwriters for ABC/Dunhill Records when they were encouraged to form a band by producer Gary Katz. He suggested guitarist Jeff “Skunk” Baxter and drummer Jim Hodder, and in 1970 they placed an ad in the Village Voice: “Looking for keyboardist and bassist. Must have jazz chops! Assholes need not apply.” Long Island native and guitarist Denny Dias responded and moved out west, before short-lived vocalist David Palmer (he only sang lead on two tracks) was added to compensate for Fagen’s initial stage fright. Though it introduced trademarks of Becker and Fagen’s partnership — unconventional chord structures, cryptic lyrical concerns and a wry, sardonic wit (as evidenced by the original liner notes credited to Tristan Fabriani, a Becker/Fagen alias) — “CBAT” (to use its social media shorthand) is probably my least favourite album by my favourite band. Having said that, this catchy LP was a hit in 1972 and includes three of the five Steely Dan tracks that can still frequently be heard at your local CVS. After two more albums Becker and Fagen grew tired of the road and fired the rest of the group in 1974. Future recordings used the cream of L.A.’s session musicians (Steely Dan didn’t tour again until 1993). This practice however had already started on their first record, which features English jazz percussionist Victor Feldman and New York guitarist Elliott Randall, whose solo on “Reelin’ In The Years” remains a highlight of the Dan’s oeuvre. Fast forward half a century and David Palmer now works as a landscape photographer in South Carolina, while Denny Dias helms an eponymous band based in Boston. Jeff Baxter enjoyed success with the Doobie Brothers, though these days he’s best known for his work as a missile defense consultant. Jim Hodder drowned in his swimming pool in 1990.

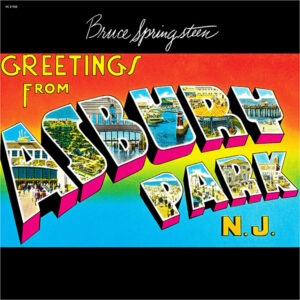

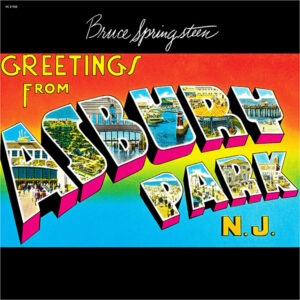

Bruce Springsteen / Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.

Bruce Springsteen / Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.

Columbia, 1973

When Bruce Springsteen’s debut album was released in January 1973, only seven months had passed since Springsteen’s audition for John Hammond at Columbia Records on East 52nd Street (a set of acoustic demos that emerged on the Tracks boxset in 1998). Hammond — who had also discovered Billie Holiday, Aretha Franklin and Bob Dylan — knew unique talent when he heard it, and wasted no time in signing the 22-year-old to a record deal. The album was cut that summer at 914 Sound Studios, a low-budget facility in Blauvelt, NY. But when the acetate was submitted that August, Columbia president Clive Davis said he didn’t hear a hit single. So Springsteen quickly wrote two extra songs, the first of which was “Blinded By The Light.” The track showcased the young songwriter’s penchant for frantic verbosity bordering on the absurd, inviting the inevitable “New Dylan” comparisons that persisted in the early part of Springsteen’s career. The single failed to chart, but Manfred Mann’s version reached number one in August 1976 — still the only Springsteen-penned song to top the Billboard Hot 100. The second late addition was “Spirit In The Night,” a soulful number that became a staple of the Springsteen’s early live shows. The line-up on this album included Garry Tallent on bass and Clarence Clemons on saxophone, drummer Vini “Mad Dog” Lopez and pianist David Sancious, whose mother lived on E Street in Belmar, NJ. The band used her garage as a rehearsal space and eventually took their name from the address. Though it introduced a prolific and daring artist, as well as some of the lyrical motifs central to his early work — teenage romance, Catholic imagery, the circus, street life, gang violence, and of course, the automobile — this is perhaps my least favourite Springsteen LP. But I have always loved “Growin’ Up,” which would have ideally opened side one. I remember my dad put it on the third compilation tape he made for me not long after I got my first Walkman around 1985. In 2018 I saw Springsteen perform it solo at the Walter Kerr Theatre as part of his Broadway show, to which I wore a T-shirt with art director John Berg’s iconic album artwork.

Little Feat / Dixie Chicken

Little Feat / Dixie Chicken

Warner Bros., 1973

Little Feat’s third album, Dixie Chicken, was their second to feature a front cover by Neon Park, whose somewhat surreal illustration style became the band’s visual signature (this one was inspired by a 1954 Revlon ad starring Carmen Dell’Orefice). As a child I remember seeing Little Feat’s LPs at home and being amused by the artwork, which more than hinted at the eccentric humour in the music. This slightly zany sensibility seemed to be a common thread among similarly-inclined West Coast acts in the early seventies, such as Dan Hicks & His Hot Licks, Commander Cody & His Lost Planet Airmen, and even Ry Cooder. Though their sound was hard to define, on this record Little Feat landed on what would become their trademark melting pot of swampy, Southern-fried funk and New Orleans rhythm and blues (the album even includes a version of Allen Toussaint’s “On Your Way Down”). Former Mothers of Invention guitarist and vocalist Lowell George had emerged as the band’s major songwriting talent, and the next two Little Feat records — Feats Don’t Fail Me Now (1974) and The Last Record Album (1975) followed in a similar vein. The 1978 live double album Waiting For Columbus was the band’s best-selling release, but by the end of the decade directions within the group had begun to diverge. In 1979 George issued a solo album entitled Thanks, I’ll Eat It Here, a title that may have been a reference to his rapid weight gain, the result of an overindulgent lifestyle characterized by binge eating, alcoholism and speed balls. In June of that year, while on tour in support of the record, George collapsed and died of a heart attack in his room at the Twin Bridges Marriott hotel in Arlington, VA. He was 34. Little Feat’s seventh LP, Down On The Farm, was released soon afterwards, then between 1988 and 2012 the remaining members of the band put out nine more albums. The 1980 Jackson Browne song, “Of Missing Persons” (the title of which is a reference to the opening line of the Little Feat song “Long Distance Love”), was written for George’s surviving five-year-old daughter, Inara, who today is one half of the indie pop duo, The Bird and the Bee.

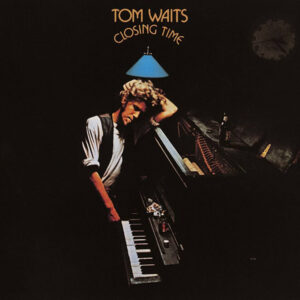

Tom Waits / Closing Time

Tom Waits / Closing Time

Asylum, 1973

Without even hearing the record, the title and cover photograph alone of Tom Waits’ debut album, Closing Time, were enough to introduce the young artist as a sort of late-night beatnik balladeer. Though Waits would persist with this identity for the rest of the decade, sometimes to the point of self-parody, it was initially developed during solo sets supporting Frank Zappa on tour and at The Troubadour on Santa Monica Boulevard. It was here that Waits’ performances caught the attention of David Geffen, who signed him to his new Asylum label. Despite the album’s nocturnal atmosphere, recording sessions took place during daylight hours since there were no evening slots available at Hollywood’s Sunset Sound Recorders. Most tracks feature acoustic guitar, upright piano and stand-up bass, though disagreements in the studio between Waits and producer Jerry Yester (formerly of The Lovin’ Spoonful) still ensued over the direction of the record: Waits wanted to make a jazz album but Yester insisted on a more folk-oriented sound. Waits’ lyrics were perhaps never more unabashedly romantic than on this record, but the production sometimes renders them perhaps more earnest compared to later releases (The Eagles even covered “Ol’ ’55” on their next LP). This is undoubtedly a record of extreme warmth and beauty that instantly evokes its place and period, even for those of us who weren’t there. The slight echo on “Lonely” expertly suggests the emptiness of a rehearsal space above a bar at 4PM (or 4AM), while “Midnight Lullaby” is probably the only song in history to mention “the British Isles” and “West Virginia” in the same line, something I’ve always enjoyed given that my wife hails from Morgantown, WV. The gorgeous after-hours arrangement of the instrumental title track that closes the album is the closest thing Waits ever made to a wordless manifesto. Waits got Bones Howe to produce his next seven releases (Yester was jailed in 2019 on child pornography charges). By the early eighties Waits’ voice had become more gravel-soaked and his work more experimental, but the line between person and persona has always remained a bit hazy.

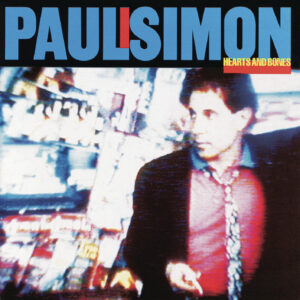

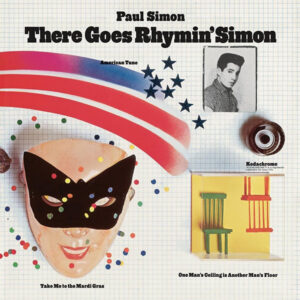

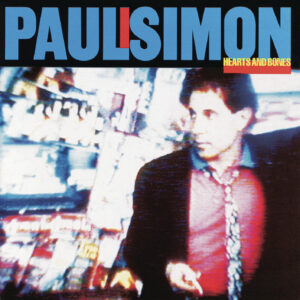

Paul Simon / There Goes Rhymin’ Simon

Paul Simon / There Goes Rhymin’ Simon

Columbia, 1973

There Goes Rhymin’ Simon was technically Paul Simon’s third solo album if you count The Paul Simon Songbook (a 1965 UK-only release), though only his second since he and Art Garfunkel had parted ways. His eponymous LP from the previous year had shown he could make more varied and personal music without his partner, but this album established Simon not just as a great pop songwriter, but also a great record maker. It’s perhaps the warmest, most accessible album in Simon’s entire discography. Though no stranger to gospel, blues and jazz, after the success of Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon began to immerse himself in the sound of the American south. Half the LP was recorded at Alabama’s Muscle Shoals studio, whose in-house rhythm section provided much of its charm. The Dixie Hummingbirds appear on two tracks, while the falsetto on “Take Me To The Mardi Gras” is by the Reverend Claude Jeter. Additional backing vocals were provided by the Roche sisters, whom Simon had met in 1971 while teaching a songwriting class at NYU. But like all of Paul Simon’s work it’s his clever songs and unexpected juxtapositions that elevate this album to another level. Though the opening track, “Kodachrome,” caused a headache when Kodak insisted a trademark symbol appear wherever its title appeared in print. For the same reason the song wasn’t released as a single in the UK since laws regarding brand names prevented it being played on BBC radio. My favourite track is probably “Something So Right,” which I’ve always loved for its deceptively simple lyrics and chord structure, but especially the odd middle eight in 3/4 time. Based on a 17th century Lutheran hymn, “American Tune” is a song my dad used to play a lot (he even recorded it). Written immediately following Nixon’s 1972 reelection, it’s perhaps the only note of despair on the entire LP, anticipating the cooler, more defeated tone of Simon’s next album, and cementing his persona as the Upper West Side’s preeminent neurotic intellectual. Appropriately enough each track was visually illustrated on the gatefold cover by another artist inexorably tied to music and Manhattan: Milton Glaser.

George Harrison / Living In The Material World

George Harrison / Living In The Material World

Apple, 1973

Living In The Material World was George Harrison’s fifth studio album and the long-awaited studio follow-up to 1970’s triple LP opus, All Things Must Pass (Harrison had released a live album documenting the Concert For Bangladesh in 1971, but back then three years was a long time in music). The new record eschewed his previous album’s sonic bombast for a more understated production, perhaps a reflection of Harrison’s interest in Hindu spirituality, which by 1973 had reached new heights of devotion. Though his devotion to other things — namely cocaine and cars — meant he was also prone at times to veering from his chosen path, sometimes literally. Harrison and then-wife Pattie Boyd were lucky to survive when he crashed his Mercedes-Benz into a roundabout while doing ninety on the M4 in February 1972. Aside from his spiritual musings, the album also revealed Harrison’s contempt for consumer culture and an increasingly corporate music industry (especially in the wake of having organized benefit concerts), as well as the expected dose of residual post-Beatles bitterness. The recording featured the usual crew of Harrison associates — Nicky Hopkins, Klaus Voorman, Jim Keltner, Ringo Starr — though notably, no Eric Clapton. This was likely due to his infatuation with Boyd and descent into heroin addiction (the guitarist had passed out mid-performance at the Concert For Bangladesh). Anyway, LITMW remains a record that’s a bit underrated and forgotten compared to ATMP, whose size and scope cast a long shadow over the rest of Harrison’s output in the seventies. Though it did provide an appropriate title for Martin Scorsese’s epic 2011 documentary on the musician’s life. Like its predecessor, the LP is also impressive for its lavish packaging: the front and back cover uses electro-photography and the interior sleeve incorporates artwork from the Bhagavad-Gītā. Living In The Material World peaked at number 2 on the UK album chart. Ironically it was kept off the top spot by the soundtrack album to That’ll Be The Day, a British rock ’n’ roll nostalgia movie starring… Ringo Starr.

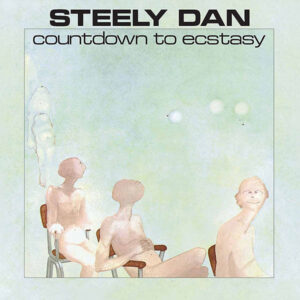

Steely Dan / Countdown To Ecstasy

Steely Dan / Countdown To Ecstasy

ABC, 1973

I first heard Countdown To Ecstasy as a teenager — before that the only Steely Dan track I was consciously aware of was “Reelin’ In The Years.” My parents had seen Steely Dan at the Rainbow in London on the band’s only visit to the UK back in 1974, an evening they often referred to as though it were a religious experience. Countdown To Ecstasy was always my dad’s favourite Steely Dan record, and one year for his birthday somebody gifted him a copy of the album on CD, back when the convenience and sonic perfection of a compact disc was still considered infinitely preferable to a worn and dusty LP. This must have been around 1994, and our CD player at the time was the kind used for deejaying, that lays flat with all the controls on top. (We had a friend who worked in the hi-fi business and he always hooked us up with stereo equipment — he’d given my dad the first model Walkman back in 1979). Anyway, this meant that when a CD reached its end, instead of stopping it simply started playing from the beginning again. I remember one afternoon listening to Countdown To Ecstasy on a continuous loop in shuffle mode, by the end of which every guitar solo and horn chart had seared into my brain. More significantly, I’d discovered my new favourite band. Steely Dan may have skewed the conventions of California rock with their clever jazz chord structures and obscure, erudite lyrics, but Becker and Fagen’s experience as Brill Building songwriters had imbued them with a pure pop sensibility. Their songs tended towards wry East Coast critiques of the contemporary L.A. scene, but their compositions were also catchy, memorable, and never indulgent — even when the band got to “stretch out” or trade fours like a bebop combo. These peculiar qualities, combined with an uncluttered studio production style, made every track Steely Dan ever recorded sound ready-made for radio, and essentially timeless. I’d heard and loved a lot of different music up to that point, but this album — though already two decades old — jolted me upright in a way that few others ever have.

Stevie Wonder / Innervisions

Stevie Wonder / Innervisions

Tamla, 1973

Stevie Wonder was still only 23 when he released Innervsisions, but it was already his sixteenth studio album, having signed with Motown when he was just eleven. For much of the sixties, the Tamla label had churned out LPs that cashed in on the musical and vocal talents of “Little Stevie Wonder.” But by the start of the seventies the “boy genius” had emerged as a progressive, singular artist that merited absolute creative control.The resulting sequence of five albums Wonder made between 1972 and 1976 are widely considered as constituting his “classic period.” Innervisions has always been my favourite of these, though thematically the record might also be the bleakest. Wonder was intent on addressing topics central to the black American experience during the turbulent days of 1973 (and 2023, for that matter): drug abuse, inequality, systemic racism, political disillusionment, even spiritual transcendence. In doing so he became both an establishment-friendly representative of the black community and, for white America, a benign messenger of its plight. Only rarely did gritty realism get the better of Wonder’s hope for social idealism, such as on the epic, cinematic “Living For The City,” whose dramatic interlude is impossible to hear without mentally directing the accompanying movie visuals. I must have quoted the line, “New York City… just like I pictured it,” out loud a dozen times during my first visit to Manhattan. The sound of Innervisions was dominated by Wonder’s innovative use of synthesizers, but he played almost every other instrument on the album as well, confirming his status as the decade’s foremost one-man-band. It perhaps also reinforced the theory that his extraordinary musical vision was directly related to the fact that he had lived his entire life without the ability of sight. Ironically, three days after Innervisions was released, Wonder was involved in a near fatal car crash in North Carolina, when a log flew off the back of a truck and struck him in the head. He lay in a coma for ten days but when he awoke his extrasensory perception only became heightened.

Jackson Browne / For Everyman

Jackson Browne / For Everyman

Asylum, 1973

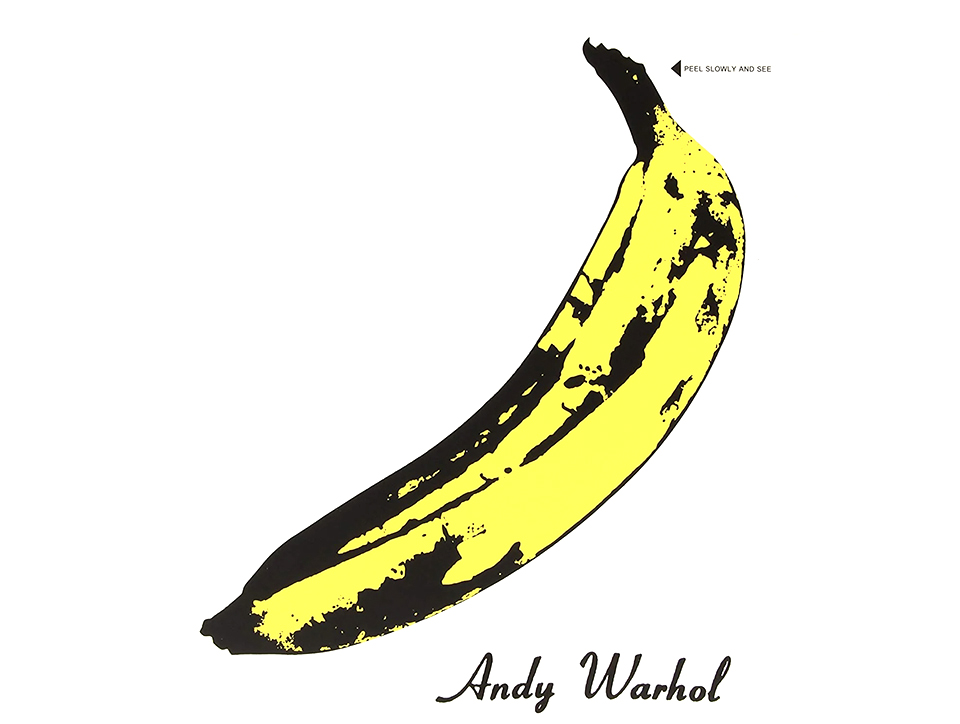

For Everyman, Jackson Browne’s self-produced second album, came out fifty years ago this month. The record’s opening track was “Take It Easy,” a song Browne had been struggling with until Glenn Frey (who happened to live in the same Echo Park apartment building) offered to help finish it. Frey apparently came up with the now-iconic line about the girl in a flatbed Ford. The Eagles’ rendition appeared on their debut album in 1972 before Browne recorded his own version. Side one closed with “These Days,” another old composition that Browne had written for a music publishing company while living in New York. The song was first recorded in 1967 as a string-laden track by German model-turned-singer and Velvet Underground associate, Nico, on her Chelsea Girl LP. Several other versions (including those by Jennifer Warnes and Gregg Allman) were released before Browne finally cut his own. The title track was written as a sort of response to the Crosby, Stills & Nash song, “Wooden Ships.” Despite the So-Cal arrangements and soaring vocals, Browne’s music was always a repudiation of sixties idealism. His songs were drenched in apocalyptic imagery and steeped in the paranoia and dread of the early seventies. With its broader social and environmental implications, “For Everyman” was at odds with the so-called “me decade,” and set the tone for Browne’s more consciously political work of the eighties. This album was the first Jackson Browne record to feature David Lindley, whose guitar and fiddle provided new texture to the music, and came to help define Browne’s sound for the rest of the seventies. Joining the aforementioned Frey are precisely the guest musicians you’d expect to find listed on a Los Angeles recording from 1973: Don Henley, David Crosby, Bonnie Raitt, Joni Mitchell… Even the honky tonk piano of Elton John (credited as “Rockaday Johnnie”) pops up on side two. The original die-cut LP cover featured a photo of the artist sitting in the courtyard of his childhood home, Abbey San Encino, in Highland Park. Using rocks from the Arroyo Seco, it was completed by hand in 1921 by Browne’s grandfather, Clyde, and is still owned to this day by his brother, Edward.

Bruce Springsteen / The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle

Bruce Springsteen / The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle

Columbia, 1973

Bruce Springsteen’s second album, The Wild, The Innocent & E Street Shuffle, arrived just eleven months after his debut LP, but in terms of ambition and execution, the distance between the two records is better measured in light years. Some observers have suggested that Springsteen borrowed the title from The Wild and The Innocent, a 1959 romantic western starring Audie Murphy and Sandra Dee. Certainly, in their scope and imagery, these poetic tales of boardwalk life and urban romance are nothing short of cinematic. There are just seven tracks on the record, four of which stretch out over seven minutes. The album moved beyond the acoustic folk-rock of Springsteen’s first record, incorporating elements of R&B and jazz into a Jersey soul stew, while wringing every eccentricity out of a carnivalesque band whose sound is as expansive as it is hyperactive. This change in direction is reflected in the band photo on the back cover, taken by David Gahr in the doorway of an antique store in Long Branch, NJ. This line-up still included David Sancious on keyboards and Vini “Mad Dog” Lopez on drums. Aside from his extraordinary piano intro to “New York City Serenade,” Sancious’ other indirect contribution to Springsteen folklore is the fact that his mother’s Belmar home was located on E Street — the band had used her garage as a rehearsal space. This album (and its title track) was the first official mention of the now-mythical address, though the band only became known as The E Street Band in September 1974, by which time Sancious had left the group with Lopez’s replacement, Ernest “Boom” Carter, to form a jazz-fusion band called Tone. Springsteen never sounded like this again: as the lives of his characters got harder and leaner, so did his songs. Following his next album, 1975’s Born To Run, his star entered the stratosphere, never to return. To this day this record remains by far his most musical, but perhaps also his most overlooked. I don’t have a favourite Springsteen album (this and the six that came after it are all essential) but I still think side two of this LP is the finest suite of music he ever recorded.

Paul McCartney & Wings / Band On The Run

Paul McCartney & Wings / Band On The Run

Apple, 1973

Band On The Run was Paul McCartney’s fifth solo album, and the third credited to Wings, though by the time recording began the band’s line-up had been reduced to just three people: McCartney, wife Linda, and loyal sideman Denny Laine. Lead guitarist Henry McCullough quit after an argument with McCartney during rehearsals for the album on his farm in Scotland; drummer Denny Seiwell followed him a week later. Perhaps inspired by the title track’s themes of freedom and escape, McCartney asked EMI to send him a list of their overseas recording facilities, from which he chose their studio in Lagos. But the exotic setting was not quite the creative idyll McCartney had anticipated. Still under military dictatorship following the end of the civil war, Nigeria was hardly a safe haven. One night Paul and Linda lost a bag of demo cassettes and notebooks of lyrics when they were robbed at knifepoint after ignoring local advice and going for an evening walk. The group only received EMI’s warning about an outbreak of cholera once they’d returned home, but during one session McCartney did suffer a bronchial spasm brought on by heavy smoking. Located in the port suburb of Apapa, the ramshackle studio had a faulty control desk and was prone to losing power, but somehow the band got enough basic tracks down to finish overdubs back in London. McCartney’s solo career had yet to reach the critical or commercial heights he’d enjoyed as a Beatle, but Band On The Run was an international success. It’s probably still McCartney’s best-known post-Beatles record, thanks also to Clive Arrowsmith’s cover photograph, which, in addition to the band, featured various notables such as Clement Freud, Christopher Lee and Michael Parkinson. My copy is actually a 1978 Dutch pressing, picked up at my go-to LP emporium Academy Records back in 2017. It’s missing the large poster included with the original version, but the opaque lilac vinyl more than makes up for it!

Joni Mitchell / Court and Spark

Joni Mitchell / Court and Spark

Asylum, 1974

They used to call the seventies “the decade that taste forgot.” Admittedly, some of the music released in 1974 has aged about as well as a bottle of Blue Nun. Which is why Court and Spark — Joni Mitchell’s sixth album and arguably the most confidently stylish record of the seventies — a reminder that there was more to that decade than bell bottoms and garish wallpaper. Instead, through its lush arrangements and extraordinary lyrical imagery, this record evokes elegant interior scenes of Halston dresses perched on Cesca chairs. To me it’s the audio equivalent of Annie Hall or the Citroën CX. Though I enjoy her earlier work, Court and Spark was the moment Mitchell shed her folk-pop origins and began a new creative ascent. Having spent most of 1973 in the studio assembling the right group of musicians to suit the jazz-oriented arrangements her sophisticated new material required, she ended up hiring saxophonist Tom Scott, whose fusion band, the L.A. Express, provided most of the backing tracks. The record also includes cameos by the Band’s Robbie Robertson, old flames David Crosby and Graham Nash, and even comedy duo Cheech & Chong. Despite the jazz line-up, it was the closest thing Mitchell ever made to a true pop album, and remains her most commercially successful release. Sales were boosted by the hit singles “Help Me” (later referenced by Prince on “The Ballad of Dorothy Parker”) and “Free Man In Paris,” written from the point of view of Asylum label boss David Geffen (who failed to convince her to leave it off the record). Combining complex studies of modern romance and jaded social critiques, Court and Spark is certainly of its time but also the first in a series of albums that represent Mitchell’s most mature and enduring work — though she alienated many casual fans in the process. My LP is an original 1974 Santa Maria pressing with embossed text and a gatefold sleeve. I’m not sure what happened to my CD copy. But you need some kind of physical format to listen to this album since Joni removed all her music from Spotify, proving once again that she is an artist in the truest sense of the word.

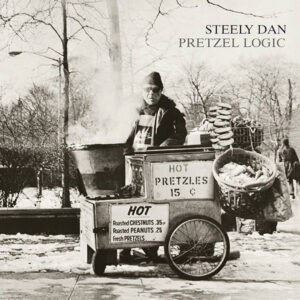

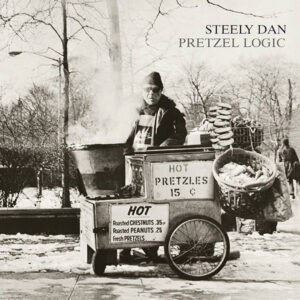

Steely Dan / Pretzel Logic

Steely Dan / Pretzel Logic

ABC, 1974

Compared to its predecessor, the material on Pretzel Logic, Steely Dan’s third album, adhered to pop convention. But these radio-friendly songs belied sophisticated bop devices, plus a cynicism and paranoia that by 1974 had all-but pervaded American life. Much of the music seemed to seek refuge in an already-forgotten past — no other Dan album was packed with quite so many overt references to its leaders’ jazz heroes. The first track and lead single, “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” flagrantly extrapolates the piano from Horace Silver’s 1964 composition, “Song For My Father.” Side two opener, “Parker’s Band,” is a swinging paean to the titular sax pioneer and the clubs on 52nd Street, even referencing two separate “Bird” tunes in the second verse. There’s even a cover of Duke Ellington’s “East St. Louis Toodle-oo,” on which Jeff “Skunk“ Baxter imitates a muted horn with his guitar’s wah-wah pedal. In May 1974 my parents saw Steely Dan at the Rainbow Theatre in London (decades later I found a bootleg CD of the show at Norman’s Sound & Vision in the East Village and sent it to them). Though by this point the touring group had expanded to include the likes of Jeff Porcaro and Michael McDonald, Pretzel Logic was the last album the Dan made as an actual band. Walter Becker and Donald Fagen cut short the tour, trading in the road for the safe haven of the recording studio. For the rest of the decade, the duo — in an at times obsessive pursuit of sonic perfection — plucked musicians as needed from L.A.’s stellar roster of session aces (as recalled with typical grandiloquence in the liner notes for the 1999 CD reissue). My gatefold LP is an original 1974 Santa Maria pressing. The cover photo was taken by Raenne Rubenstein on the west side of Fifth Avenue near the 79th entrance to Central Park, just south of the Metropolitan Museum. On the back cover the twin towers of the San Remo apartment building on Central Park West are clearly visible through the bare trees. In fact half a century later little in this photo has changed, with the exception of 15-cent “pretzles.” Those days are gone forever, over a long time ago… oh yeah.

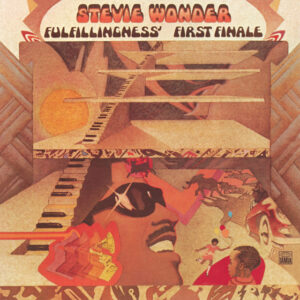

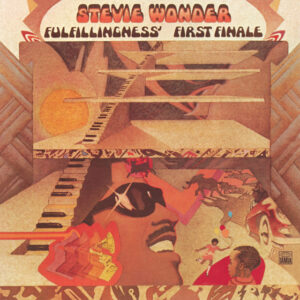

Stevie Wonder / Fulfillingness’ First Finale

Stevie Wonder / Fulfillingness’ First Finale

Tamla, 1974

Though Stevie Wonder was still only 24 at the time, Fulfillingness’ First Finale was already his seventeenth studio album. Though it went to the top of the Billboard album charts, this record is definitely the most forgotten and overlooked of Wonder’s so-called “classic period” (even by me). That might be due to the awkward, alliterative title: is “fulfillingness” even a word? On top of that the sleeve was printed on a matte cardboard, stripping detail from Bob Gleason’s elaborate artwork and rendering the package a bit dull and murky. Having said that, this is a contemplative and strangely beautifully LP that rewards repeated listens, and one that is truly emblematic of the sophisticated one-man band studio wizardry and mind-altering chord progressions that by 1974 put Wonder in a genre of futuristic art-soul entirely of his own creation. Michelle Obama calls this her favourite album of all time, and it’s not hard to imagine why. FFF (as probably nobody else calls it) is perhaps best-remembered for its singles, the funky “Boogie On Reggae Woman” and the angry “You Haven’t Done Nothin’,” a bitter diatribe aimed at Richard Nixon (the disgraced president resigned from the White House two days after the 45 came out). The LP’s most sombre track, “They Won’t Go When I Go,” was covered by George Michael on his second solo album, which I actually prefer to the original. In 1975 Wonder took home his second consecutive “Album of the Year” Grammy. In 1976 the award went to Paul Simon, who thanked Wonder for not making an album that year.

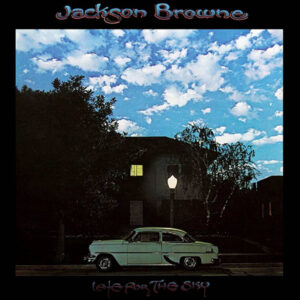

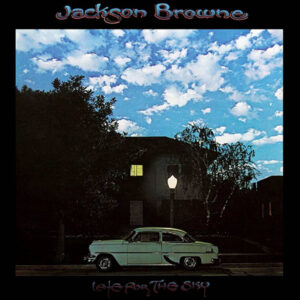

Jackson Browne / Late For The Sky

Jackson Browne / Late For The Sky

Asylum, 1974

If you’re anything like me, you can probably summon a mental shortlist of albums that mean more to you than all the others. I’m talking about the records that through repeated listens over many years have passed the point of mere familiarity, to the extent that they feel more like a part of your personal history or even an extension of your own self. For me, this album is one of those. Late For The Sky was Jackson Browne’s third LP, and expanded on some of the heavy themes — love, death, identity, alienation, adulthood — mapped out on the first two. But unlike those records, on this one there we no hits, and barely any hooks. There are only eight tracks on this album, six of which stretch out like expansive poems. At just 25, Browne had already proven himself a lyricist of rare eloquence and perspective, but there was nothing indulgent or pretentious about his writing. These songs were more like sermons, and a perfect match for his extraordinary voice: simple, soaring, searing. It all feels as natural and as transcendent as flying. Browne became the quintessential Los Angeles singer-songwriter, but he’d cut his teeth as a precocious teen in the Greenwich Village scene. In traversing these two seemingly disparate pop schools, no artist so accurately encapsulated the American mood of the first half of the seventies, as a generation’s youthful idealism and aspirations gave way to disillusionment, resignation, paranoia and fear (the title track was used, somewhat incongruously, in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver). Though the seemingly mellow West Coast arrangements make this record sound very much of its time, it was also years ahead of it. With its apocalyptic imagery and universal chorus of hope, side two closer “Before The Deluge” warns of the dangers of indifference — both environmental and social — predicting the rise of yuppie culture and pre-empting Browne’s own political activism of the eighties. The iconic cover was shot on South Lucerne Avenue in Windsor Square. The concept was Browne’s (“if it’s all reet with Magritte”), as was the car, a 1953 Chevrolet Bel-Air, apparently given to him by his former roommate, Glenn Frey.

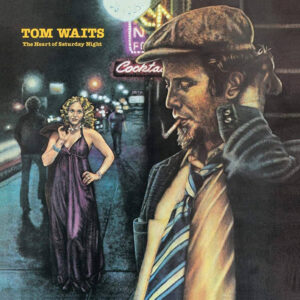

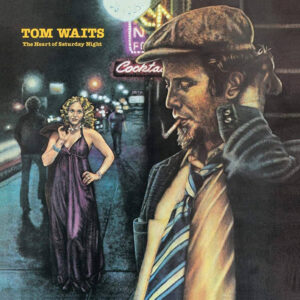

Tom Waits / The Heart Of Saturday Night

Tom Waits / The Heart Of Saturday Night

Asylum, 1974

The cover for Tom Waits’ second album, The Heart Of Saturday Night, was apparently inspired by the artwork for Frank Sinatra’s 1955 album In The Wee Small Hours, but I never liked it — it always felt too literal, and a bit corny. The two photos taken by Scott Smith in front of a Los Angeles newsstand on the reverse sleeve would have made a much better front and back cover pairing. There’s even plenty of dark negative space where the text could go. But perhaps instead of retroactively redesigning LP artwork half a century after the fact I should talk about the record itself. The album expands upon the after-hours folk-jazz of Waits’ 1973 debut, but this time the setting is a night on the town, consecrating the artist’s enduring seventies persona as a boozy nocturnal troubadour. This album was also the start of a decade-long partnership with Bones Howe, who went on to produce all of Waits’ LPs on the Asylum label. The title track tackles the kind of themes that Waits’ contemporary Bruce Springsteen was writing about circa 1974. But while Springsteen’s early songs were fueled by the possibilities of youth, Waits’ characters seemed already resigned by life’s limitations. Waits himself always appeared like a man out of time, a product of L.A.’s early-seventies nostalgia for the jazz age who, by twenty-five, had seemingly already lived a life’s worth of heartbreak. Most tracks incorporate a standard rhythm section of seasoned jazz session players, though some include strings arranged by Mike Melvoin (Wendy’s dad). Two tracks — “Diamonds On My Windshield,” on which Waits raps like a Beat poet over a relentless bassline, and the almost spoken word closer, “The Ghosts Of Saturday Night” — hint at the direction Waits would take on subsequent albums. On The Heart Of Saturday Night his caramel croon was still intact, but by the time Small Change came out in 1976, his music had become more idiosyncratic, and his voice raspier, at times approaching a soon-to-be-customary growl. I love all of Waits’ seventies albums, but this is probably the one I’ve played the most. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I’ve never listened to it in the daytime…

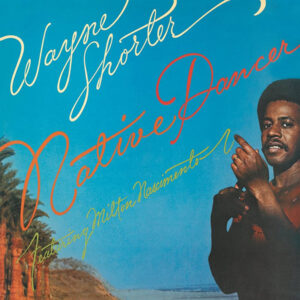

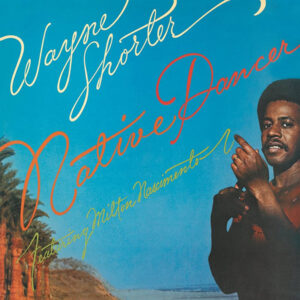

Wayne Shorter featuring Milton Nascimento / Native Dancer

Wayne Shorter featuring Milton Nascimento / Native Dancer

Columbia, 1975

I was well into my thirties before I discovered Native Dancer, a collaboration between Wayne Shorter and the Brazilian singer Milton Nascimento. I kept seeing it at my local used vinyl emporium, Academy Records; eventually I picked it up and it immediately became one of my favourite albums. I played it a lot at our apartment on East 11th Street, but I have two distinct memories of hearing it in less likely places. The first was on an extremely expensive stereo at an audiophile friend’s house during a ski weekend upstate (he’d actually met Shorter once). The second was through cheap headphones on a flight from Buenos Aires to São Paulo in 2014. I put this album on as we started our descent, and spent the next forty minutes gazing out over the sprawling metropolis as it passed by my window, seemingly without end. The album finished before the plane landed.

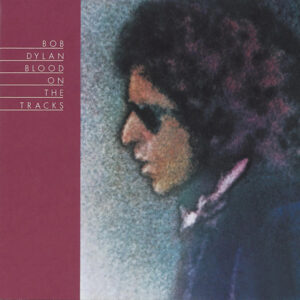

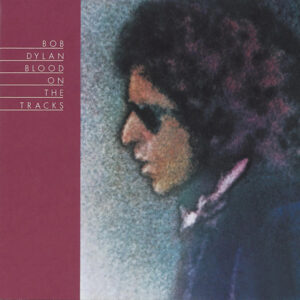

Bob Dylan / Blood On The Tracks

Bob Dylan / Blood On The Tracks

Columbia, 1975

Bob Dylan’s inconsistent output in the first half of the decade had thrown into question his relevance in the seventies; Blood On The Tracks secured his enduring reputation as an elusive artist capable of surprise reinvention. Though Dylan has typically refused to be drawn on the subject, this “comeback” record’s confessional lyrical content is famously noted as relating to the breakdown of his marriage to Sara Lownds. Their son, Jakob, has described the songs as “my parents talking.” In early 1974 Dylan began a relationship with Ellen Bernstein, an employee at Columbia Records. Around the same time he began attending art classes five days a week with the painter Norman Raeben, an experience that made him reconsider his understanding of space and time. Dylan credits Raeben for showing him how to create narratives that placed “yesterday, today and tomorrow all in the same room.” It was Raeben that described one of Dylan’s paintings as being “tangled up in blue.” Dylan once said he wrote that song after spending a weekend listening to Joni Mitchell’s 1971 album, Blue, whose intimate sound he also sought to emulate. Indeed, he initially intended to cut the new songs with an electric band before reverting to simpler acoustic arrangements. The sessions took place in New York in September 1974, but after playing the album for his brother, Dave Zimmerman, Dylan was convinced to re-record five of the ten tracks with different musicians in Minneapolis just after Christmas. Three of the LP’s songs have been performed only once in concert; several others were reimagined for the Rolling Thunder Revue tour in late ’75, and have remained part of Dylan’s live repertoire ever since. As someone who was born too late to experience Dylan as a cultural phenomenon in real time, navigating his vast discography after the fact was a daunting task. But this record soon became one of my favourites: its literary yet relatively direct relationship songs were perhaps easier for a nineties teenager to connect with than those borne from the distant folk or blues traditions that Dylan had written just a decade prior.

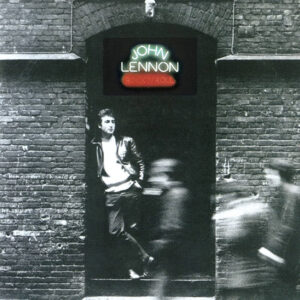

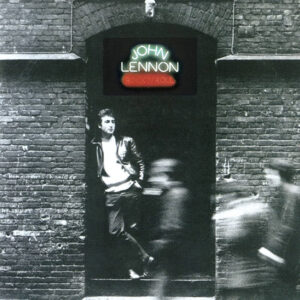

John Lennon / Rock ’n’ Roll

John Lennon / Rock ’n’ Roll

Apple, 1975

Rock ’n’ Roll, John Lennon’s sixth post-Beatles album, came about after New York music publisher Morris Levy belatedly noticed that the opening line of “Come Together” (on the Beatles’ Abbey Road) was lifted from Chuck Berry’s “You Can’t Catch Me.” As part of the lawsuit settlement, Lennon would have to record three Levy-owned songs on his next album. Instead, he chose to cut an entire LP of covers, tentatively titled “Oldies But Mouldies.” By this point Lennon was living (at the urging of Yoko Ono) in Los Angeles with the couple’s personal assistant, May Pang. Lennon would later refer to this period as his “Lost Weekend,” after the Billy Wilder film. Though Lennon’s 18 months on the West Coast became infamous for his public displays of drunkenness, at Pang’s encouragement he also reconnected with his son, Julian, whom he hadn’t seen in two years. Eventually the couple returned to Manhattan, renting an apartment on East 52nd Street and adopting two cats, Major and Minor, before John returned to Yoko in February ’75. The idea of an oldies record wasn’t new: both David Bowie and Bryan Ferry had put out albums of sixties covers in 1973, by which point a rock and roll revival was in swing, a fad spurred in part by nostalgic movies such as American Graffiti. Even Ringo Starr had, er, starred in a hit British flick called That’ll Be The Day. In early ’74 the sitcom Happy Days launched on ABC — John and Julian were early visitors to the set. Lennon brought in Phil Spector to produce the album, but the October ’73 sessions soon descended into alcohol-fueled mayhem. After an intoxicated Spector fired a gun into the ceiling (while inexplicably dressed as a surgeon), Lennon was banned from the studio. Spector then absconded with the tapes, forcing Lennon to start from scratch. Today, much of this record sounds quite ersatz to my ears — maybe the best thing about it is Jürgen Vollmer’s cover shot of a young Lennon in a Hamburg doorway. In 1975 the oldest of these songs was just twenty years old, which I think speaks to the impact of everything that had happened, musically and culturally, since 1955. Or perhaps nostalgia just ain’t what it used to be…

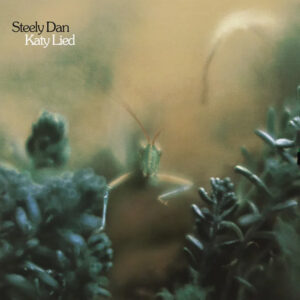

Steely Dan / Katy Lied

Steely Dan / Katy Lied

ABC, 1975

Katy Lied, Steely Dan’s fourth album, took its name from a line in “Doctor Wu,” while the insect on the cover is a katydid, a visual pun on the title. It was the first Steely Dan album following the dissolution of the touring band in 1974; for the rest of the seventies Steely Dan would exist purely as a studio entity, with a rotating cast of L.A. session musicians selected by Walter Becker and Donald Fagen on a track-by-track basis. It was also the first Steely Dan record to feature the backing vocals of Michael McDonald, whose era-defining voice pops up on the second pre-chorus of “Bad Sneakers.” But Katy Lied is probably most notable for the emergence of Jeff Porcaro. The son of jazz drummer Joe Porcaro, young Jeff had played drums as a nineteen-year-old on “Night By Night” on Steely Dan’s previous LP, Pretzel Logic. Now barely into his twenties, he sat behind the kit on nine of Katy Lied’s ten tracks (the legendary Hal Blaine takes over on the tenth). Porcaro went on to form Toto, while also playing on hundreds of records as a session musician until his death in 1992. He’d become ill after spraying his lawn with insecticide; a coroner later determined he died from a heart attack caused by years of smoking and cocaine use. Becker and Fagen were typically dissatisfied with the finished album’s sound quality, supposedly due to a malfunction with a nascent noise-reduction system. Just last month a remastered UHQR edition was released, to the great excitement of audiophiles, but both my 1975 LP copy and my 1999 remastered CD have always sounded pretty flawless to me. I used to have an MCA vinyl reissue from the eighties, but I replaced it with this original ABC pressing (complete with innersleeve), which I found a few years ago at Arroyo Records in Highland Park. According to a sticker on the reverse, it once belonged to a South Pasadena resident named Thomas C. Oddone, who himself sounds a bit like a character from a Steely Dan song. Incidentally, that same afternoon who should I run into taking out his recycling but unmistakeable session bassist Leland Sklar, who somehow never played on a Steely Dan session.

James Taylor / Gorilla

James Taylor / Gorilla

Warner Bros., 1975

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I’ve always had a certain affinity for JT, an unlikely bond that was assigned to me at birth. Luckily I’ve always liked his music (imagine the burden of going through life with the name “Phil Collins”). My parents had all of James Taylor’s records, but in 1979 they probably couldn’t have conceived he’d still be famous several decades later. It was only as an adult that I discovered James Taylor had a brother named Alex — which is also my brother’s name! Not a week goes by that a stranger doesn’t remind me of my wealthier and balder namesake. Over the years I’ve come to expect it every time I arrive for an appointment or call a customer service number, along with the requisite, “I bet you get that all the time, don’t you?” that inevitably follows. (Sometimes I respond, “No, actually you’re the first.”) Although in recent years I’ve noticed a growing number of younger people in whom my name fails to illicit any reaction whatsoever, suggesting there might come a time in my life when these comforting little exchanges are just a memory.

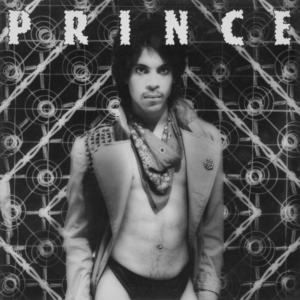

Prince / Dirty Mind

Prince / Dirty Mind

Warner Bros., 1980