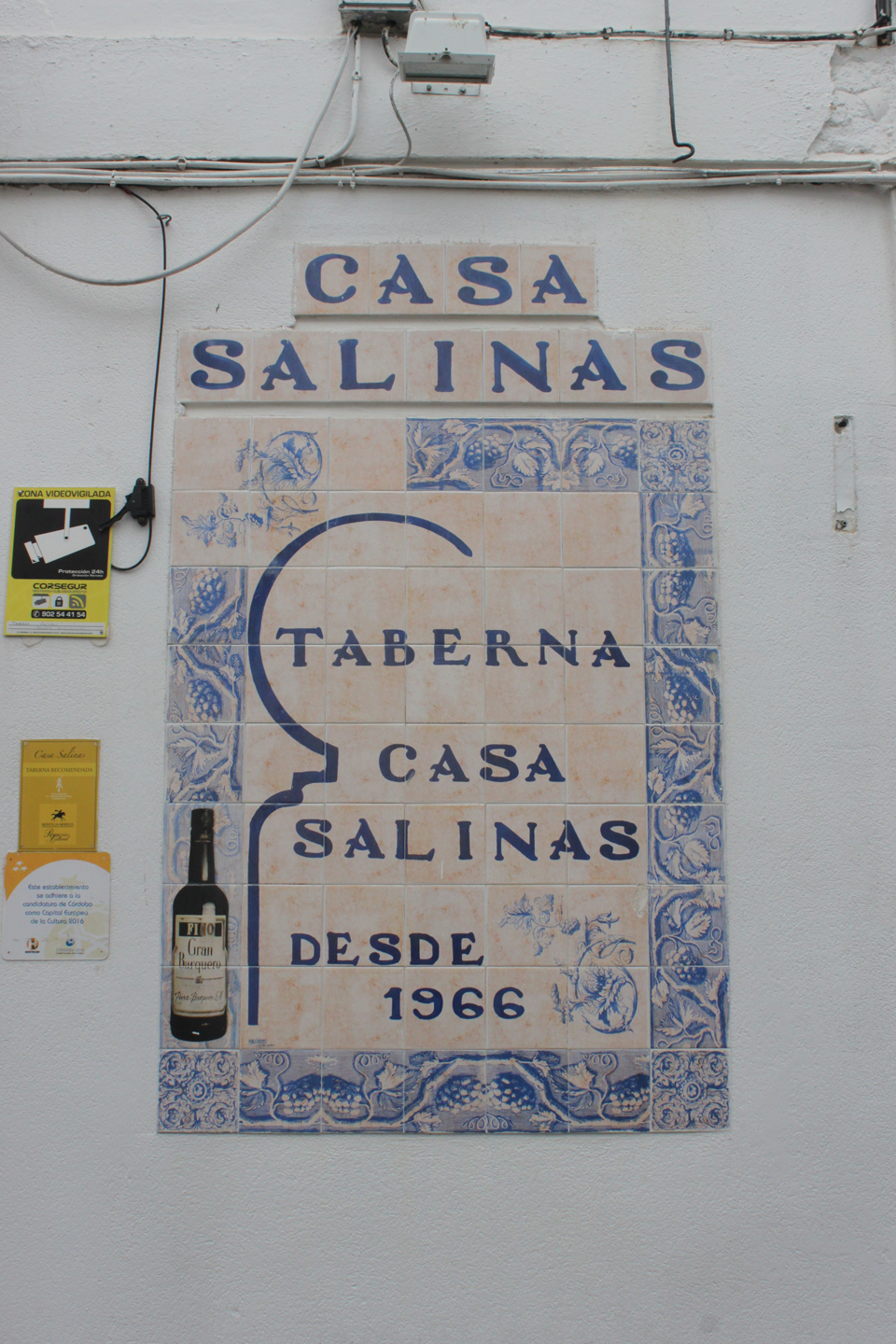

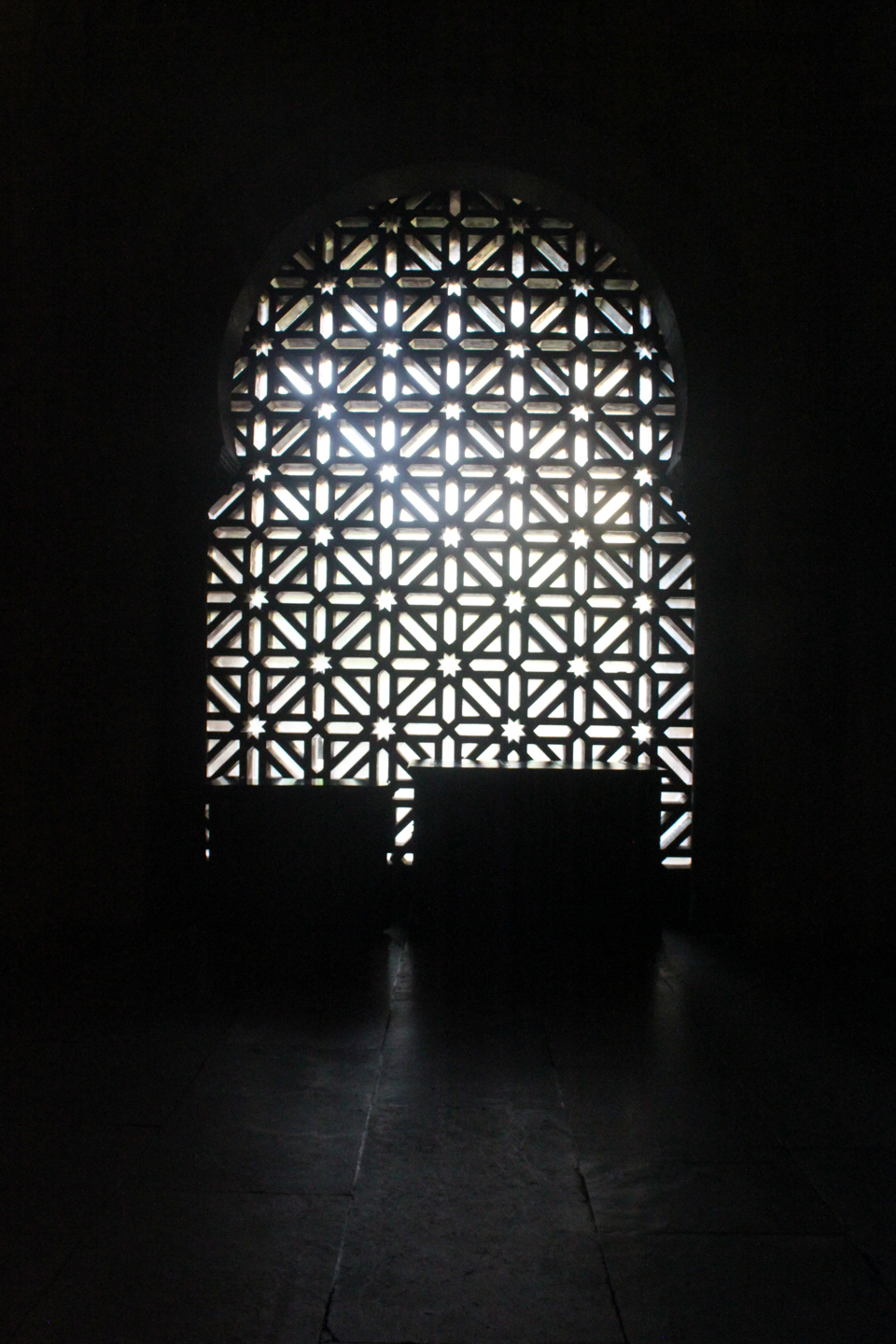

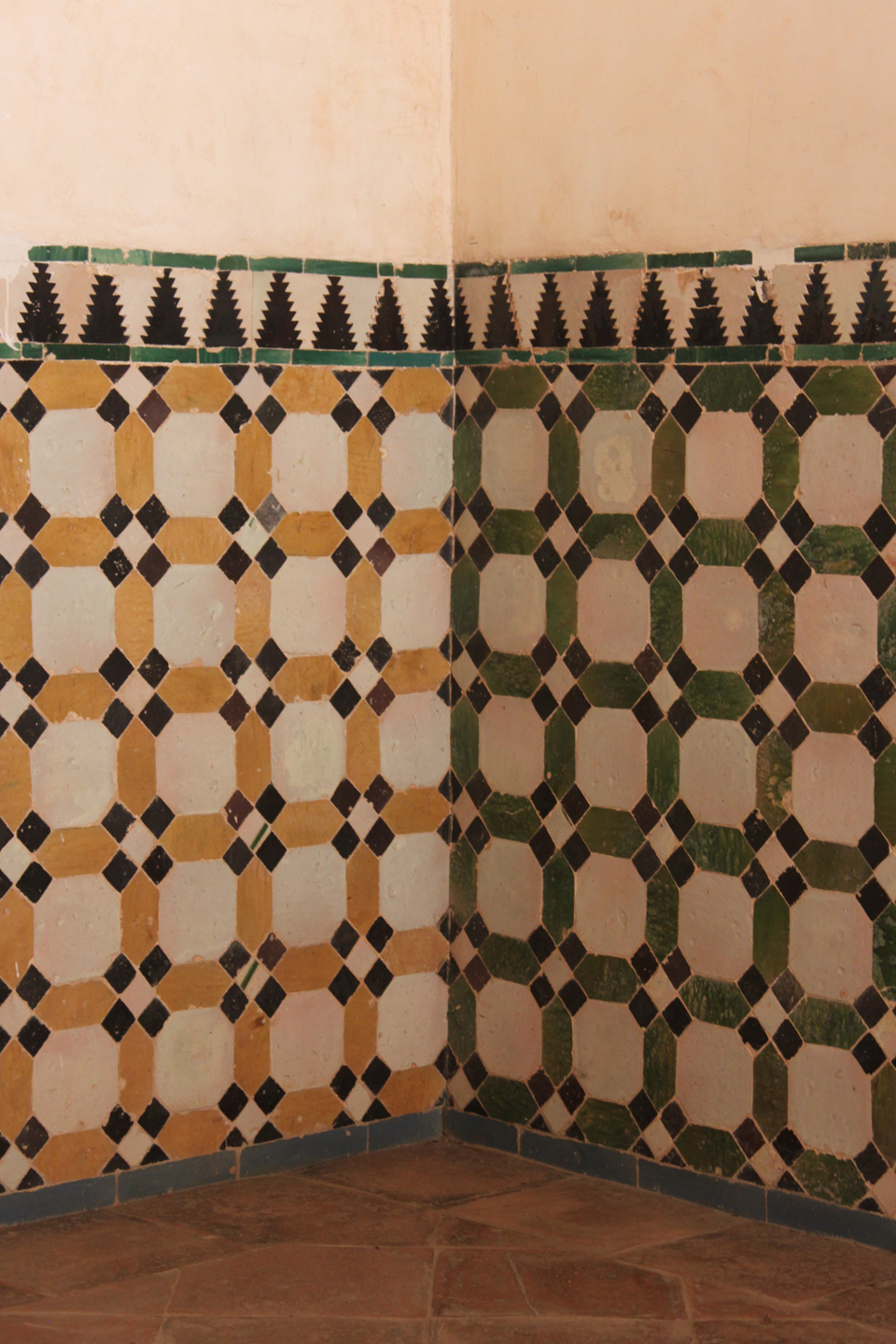

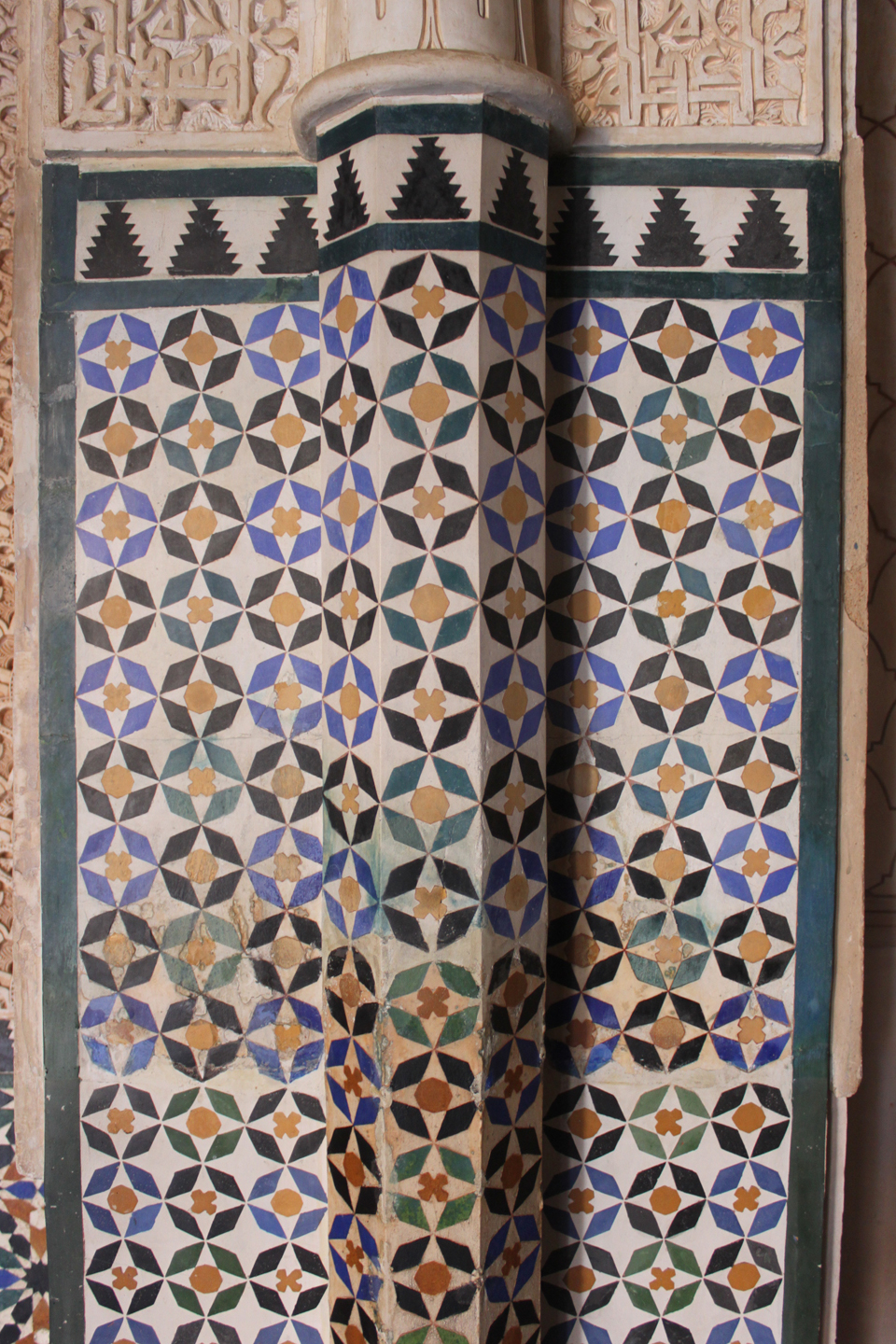

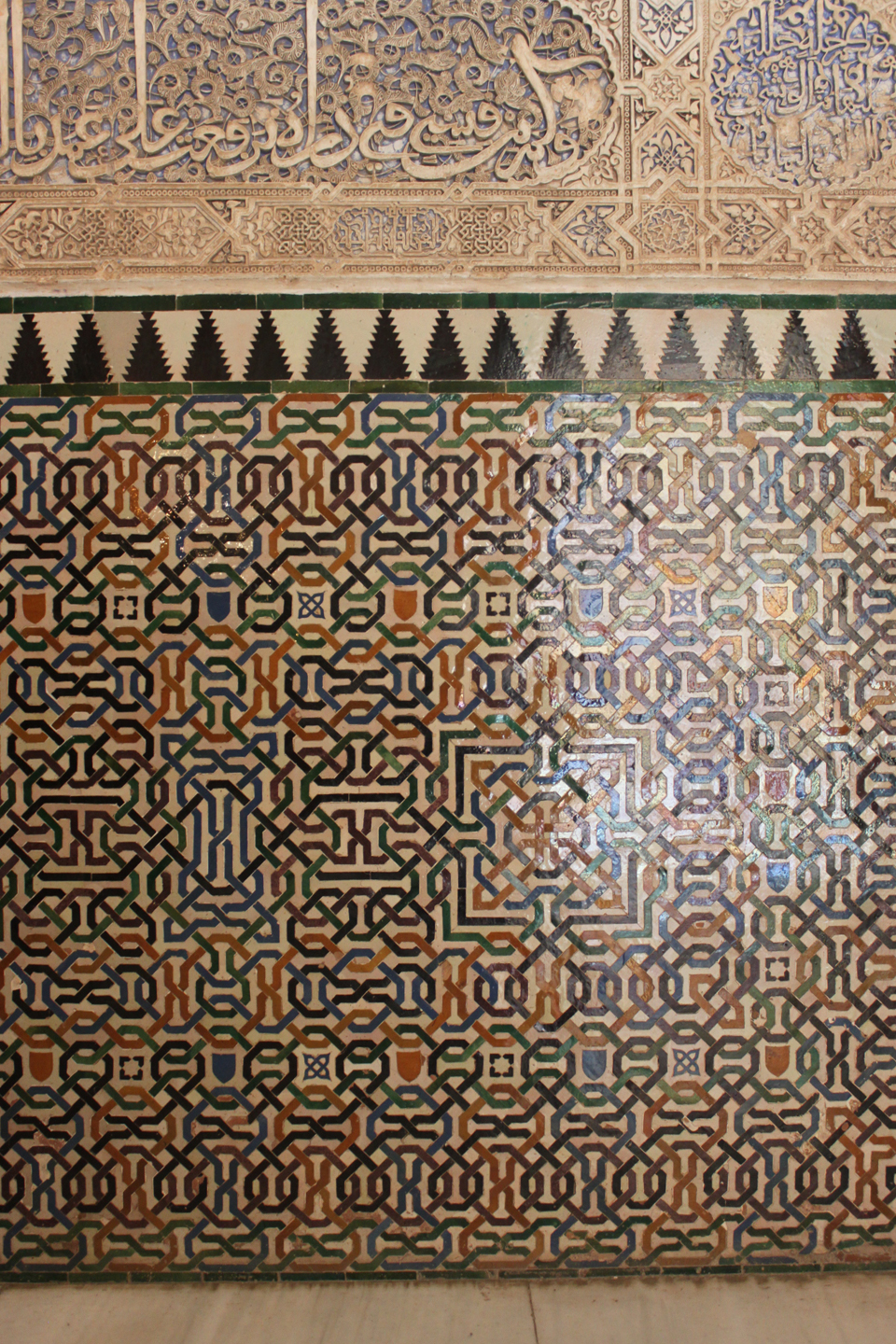

Córdoba, January 2016.

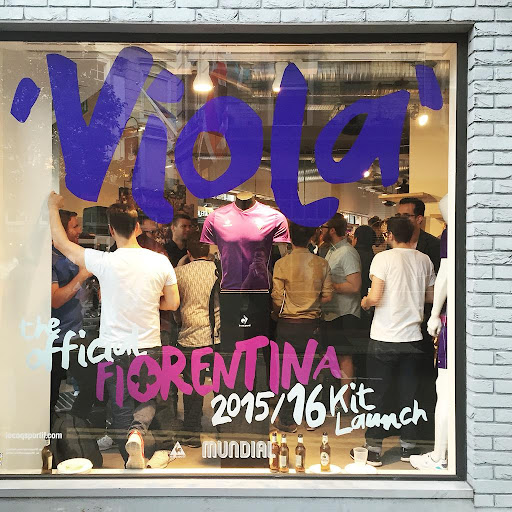

In addition to producing artwork for the official Fiorentina 2015-16 kit launch at the Le Coq Sportif flagship store in London’s Covent Garden, I also wrote articles on two of Fiorentina’s former captains, Giancarlo Antognoni and Angelo Di Livio. The work was included in a special Gazzetta-inspired free newspaper, appropriately entitled Viola, and handed out to guests at the event.

Read both articles here.

I was extremely proud to be invited by the good folks at Mundial to produce artwork for the official Fiorentina 2015-16 kit launch. My illustration of Giancarlo Antognoni was exhibited alongside those of several other Viola legends at an event hosted by the magazine at the Le Coq Sportif flagship store in London’s Covent Garden. Given my purple allegiance I was also more than happy to write a short article on Fiorentina’s legendary captain for the accompanying publication, Viola, produced especially for the occasion.

See more of the event on the official Fiorentina website!

In August Mundial magazine organized the official UK launch event of Fiorentina’s 2015-16 home kit at the Le Coq Sportif store in London’s Covent Garden. As a lifelong fan I was delighted to provide artwork and articles for “Viola”, a special newspaper produced especially for the occasion, in which the following profiles of two Fiorentina legends appeared.

As perhaps befits a man born on April Fool’s Day, Giancarlo Antognoni’s career can be reviewed as a series of cruel “pesce d’aprile” jokes. Considered one of the finest Italian players of his generation, and to this day revered by the people of Florence, the midfielder was also blighted by dreadful luck. Whenever success appeared a possibility, so that chance would be routinely snatched away. When triumph did arrive, it was twisted into bitter disappointment.

When Antognoni was a boy growing up in the Umbrian town of Marsciano, his father ran a bar in Perugia that doubled as headquarters for the local Milan supporters’ club. Like many football-loving Italians of his generation, young Giancarlo idolized Gianni Rivera. Just hours after his debut for Fiorentina at Verona in October 1972, Antognoni was already being mentioned in the same breath as the rossoneri’s famous number ten. High praise for an eighteen-year-old brought into the side to replace scudetto-winning hero Giancarlo De Sisti.

The young midfielder had been playing for an obscure team in Serie D just a few months earlier. But Fiorentina’s manager at the time, the giant Swede Nils Liedholm, never shirked away from giving youth a chance (he later granted Serie A starts to fellow teens Giuseppe Giannini and Paolo Maldini). When De Sisti followed Liedholm to Roma in 1974, he vacated much more than the number ten shirt and captain’s armband. For players and coaches, Fiorentina is often described as a “piazza difficile”, not least because of the city’s passionate yet demanding fans; Antognoni’s promotion was both an opportunity and an obligation.

With his Winwood-esque boyish looks and wavy golden hair, it didn’t take long for Florence to fall for “Antonio”, as he would soon become known. Italian football’s first young star of the seventies, it was Antognoni’s speed, elegance of movement and rare passing vision that compelled influential journalist Gianni Brera to describe him as “il ragazzo che gioca guardando le stelle” (the kid who plays while watching the stars). Recognizing their captain’s star power, the fans on the Curva Fiesole came up with their own, albeit more down-to-earth, nickname: “ENEL”, after the electricity company.

Antognoni continued to shine as Fiorentina started the 1980s brightly, until in November 1981 his lights went out — literally. Racing onto a ball from midfield, “Antonio” attempted to head past the onrushing Genoa goalkeeper Silvano Martina, only to receive a brutal and deliberate knee to the skull. Lying motionless inside the penalty area, the Fiorentina captain suffered a temporary cardiac arrest on the pitch before being rushed to hospital for emergency surgery on a cranial fracture. His return to action just four months later boosted la Viola’s ambitions in their race for the scudetto, but on the final day of the campaign they could only muster a goalless draw against Cagliari. Meanwhile in Catanzaro, a dubious late penalty converted by Liam Brady ensured Juventus won 1-0 and were crowned champions.

Later that summer in Madrid, Antognoni became a World Cup winner. For the twenty-eight year old it was undoubtedly the greatest moment of his career, but even this achievement was tarnished. Frustrated after seeing a fourth goal harshly disallowed in Italy’s famous 3-2 victory over Brazil, Antognoni had gone into the semi-final with Poland determined to right the wrong by getting his name on the scoresheet. His overzealousness led to a strong collision with defender Matysik as he prepared to shoot, and an injury that ruled him out of the final. A focal point of Enzo Bearzot’s national side for years, Antognoni was forced to witness the memorable triumph of his fellow Azzurri from the press box of the Bernabeu. To add harsh insult to his latest injury, burglars later broke into his home and stole his gold winner’s medal.

More setbacks followed. In February 1984 purple title hopes were dashed once again when Antognoni fractured his tibia and fibula in a challenge with Sampdoria’s Luca Pellegrini. As Fiorentina prepared to endure the 1984-85 season without their talisman, Socrates was brought in as a high-profile replacement. But the languid Brazilian seemed to oppose the Italian approach to training, and the team subsequently slumped. By the time their captain finally regained fitness Fiorentina had already signed Roberto Baggio (although his own debut for the club was delayed due to serious injury). Antognoni’s last two seasons in Florence were marred by injuries and managerial disagreements, and he left of his own accord to conclude his playing days in Switzerland.

A single Coppa Italia from 1975 was the only silverware to point to from his fifteen seasons with la Viola. Had he taken the opportunity to reunite with Liedholm at Roma, or accepted any of Gianni Agnelli’s several invitations to join his Italy teammates at Juventus, Antognoni would have surely earned a heftier trophy haul. Instead he traded in these successes for a much rarer reward: to become a bandiera, a club legend, and enjoy the mutual benefits that such status affords, even long after the boots have been loaned to the club museum’s permanent collection. Though his relationship Fiorentina’s ownership has been strained in recent years, the viola fans have remained ever loyal to Antognoni, just as he refused to abandon them. As he has often maintained, “The love of an entire city is worth more than a scudetto.”

To say that 2002 was not a good year for Fiorentina would be an understatement. The Tuscan side began the summer with relegation from Serie A after losing their final seven matches of the season, scoring just one goal in the same period. Three months later the club had declared bankruptcy and plunged a further two divisions, before finally being stripped entirely of their identity and history.

Almost overnight Fiorentina’s squad dispersed in all directions, and the new club — Florentia Viola, as they became legally known — was hastily assembled as a mixed bag of unknowns. The one exception was Viola captain Angelo Di Livio, who at thirty-six could have been forgiven for finding a one-year contract elsewhere or even calling time on an illustrious career. But instead, the Italian international — who’d played at the World Cup earlier that summer — accepted the challenge to start from scratch in Serie C2.

A native of Rome, Di Livio had arrived at Florence in the summer of 1999 after six years in Turin, where he’d been an important cog in Marcello Lippi’s Juventus side that reached three Champions League finals in a row. Discarded by the bianconeri, he’d reunited at Fiorentina with his former coach, Giovanni Trapattoni, the man who’d given the player his first taste of Serie A at the relatively late age of twenty-seven.

It was easy to see why Juve teammate Roberto Baggio dubbed him “il soldatino” (the little soldier). A tireless and versatile midfielder, Di Livio was content to patrol either flank like a tightly wound-up toy. If fresh orders arrived from the bench to move into a central position or drop back and support the defence, he’d simply adjust his game accordingly without fuss.

Di Livio had grown accustomed to winning, picking up three Serie A titles, a UEFA Cup, a Champions League and an Intercontinental Cup during his time in Turin. Following Fiorentina’s most successful campaign in years, there was a genuine chance he could continue that success in Florence. But an entertaining European run and a Coppa Italia victory in 2001 were as good as things would get. Following the departures of Gabriel Batistuta, Rui Costa and Francesco Toldo, Di Livio took over the captaincy. But the significantly depleted team struggled, and the fear of relegation quickly mellowed into inevitability.

In Serie C2, Di Livio’s hardwork and humility were just the attributes required if the side were to drag themselves out of footballing obscurity. Backed by the city’s tremendous and unwavering local support, la Viola won promotion up to C1, but the expansion of Serie B allowed room for one more team. Fiorentina (they’d bought back their name at this point) were granted entry into the second division on “historic merits”, and at the end of the season a play-off victory over Perugia sealed promotion back to Serie A, a mere two years since they’d left.

As la Viola adjusted to life back in the big time, Di Livio stuck around for one more turbulent season, in which the side eventually staved off another relegation. As the one player to survive the club’s rapid demise and dramatic return to top flight football, il soldatino has since come to symbolize Fiorentina’s plight and period of instability. His choice to focus on the team rather than the individual may have been the ultimate act of footballing loyalty, as well as proof that a good soldier never complains.

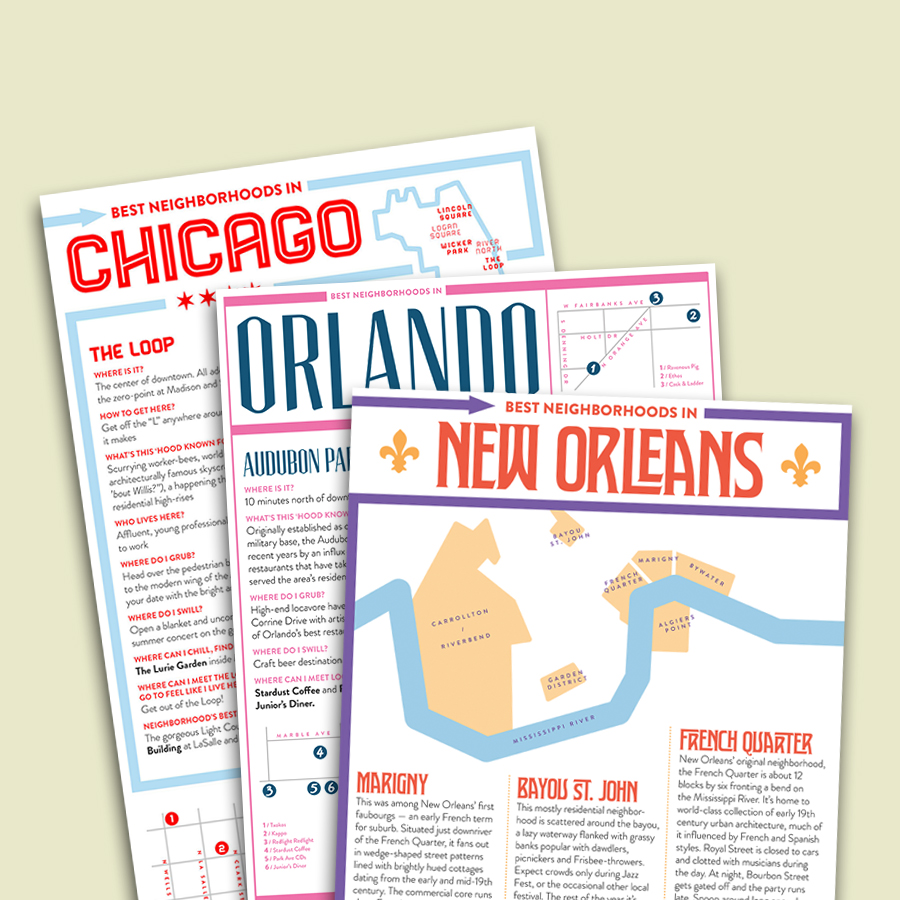

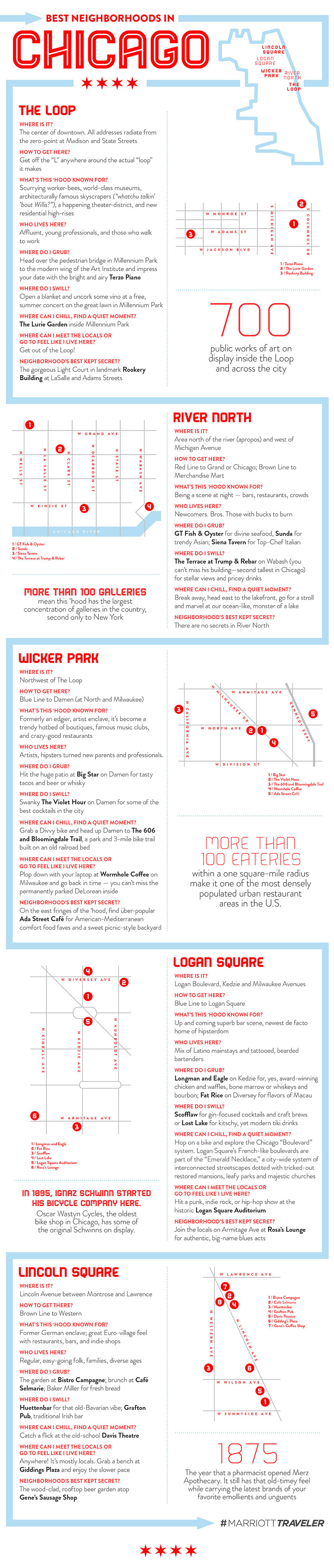

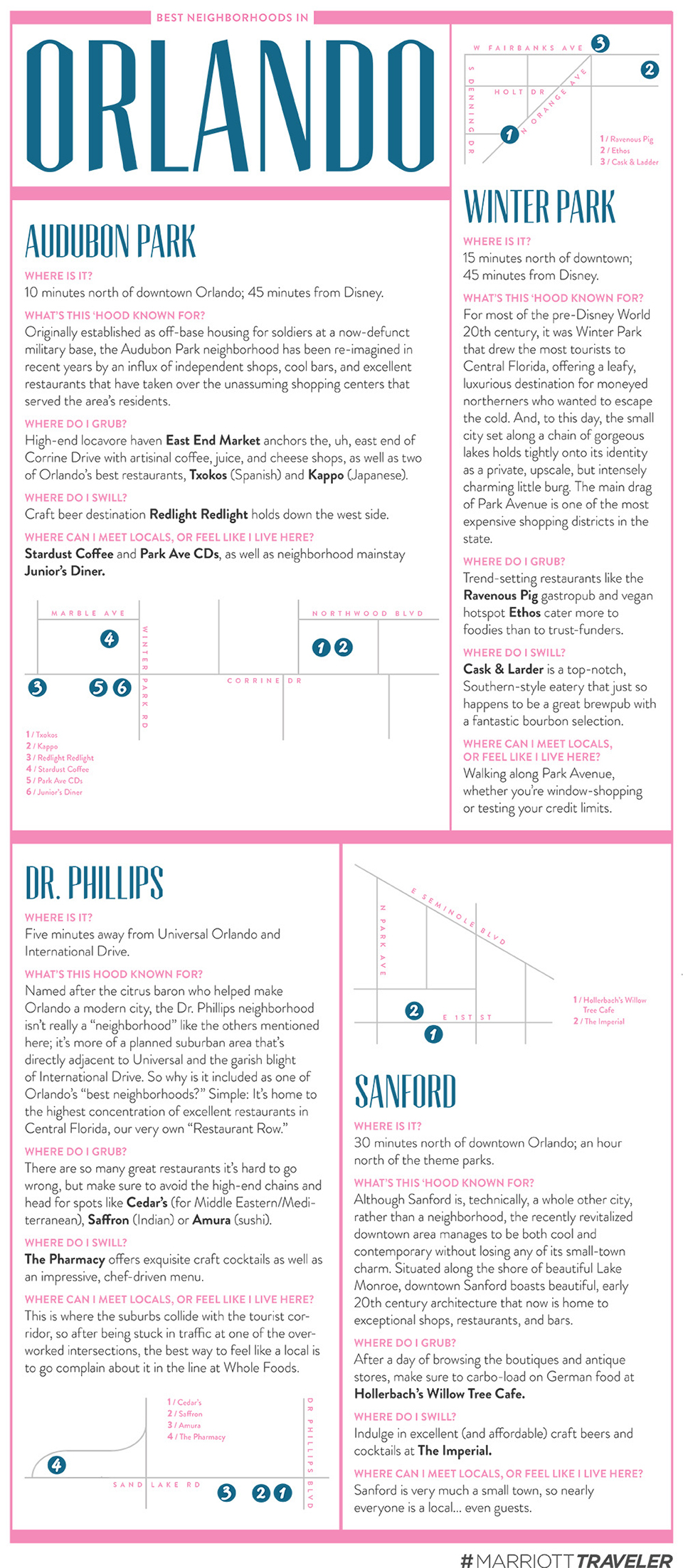

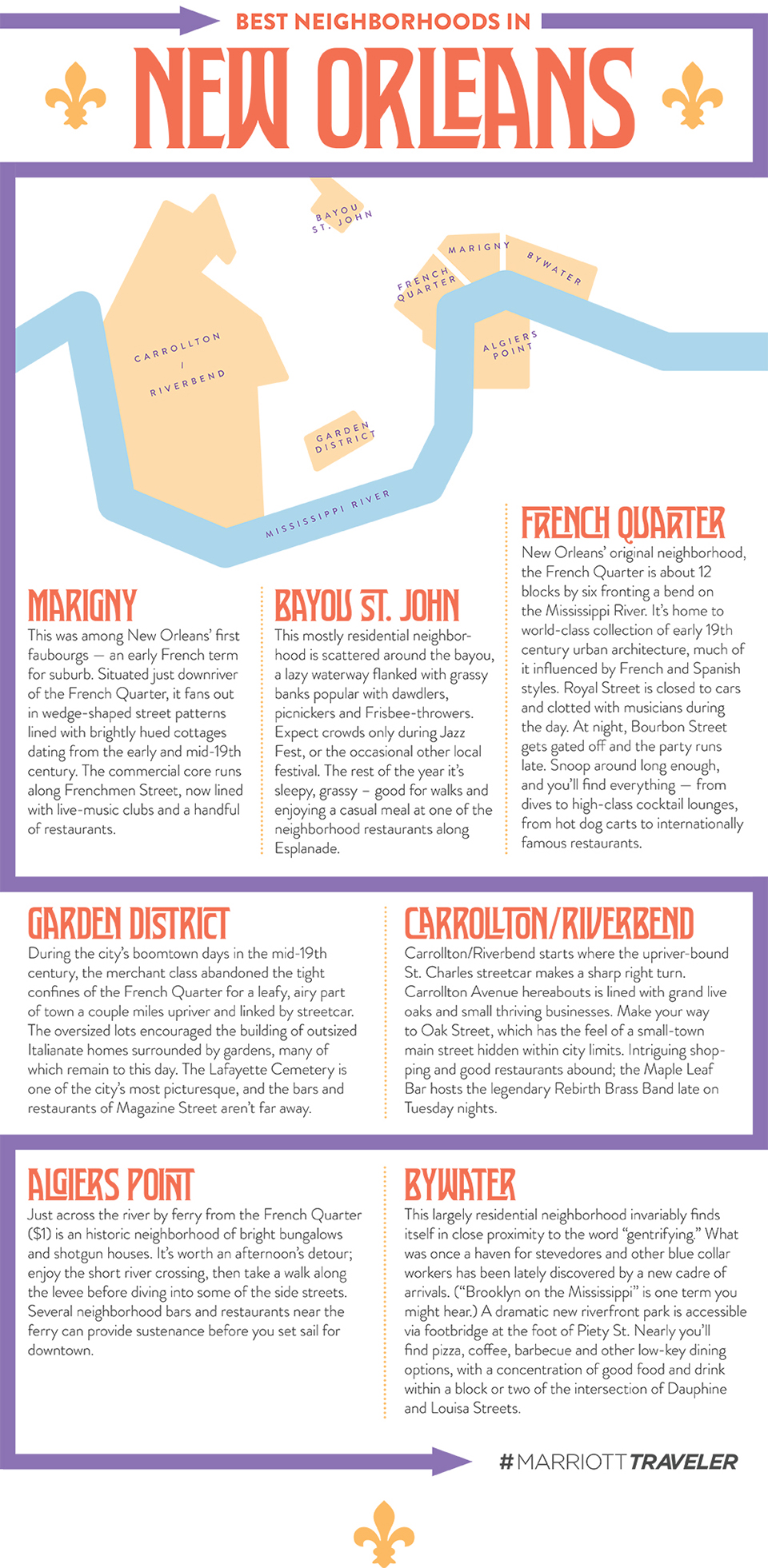

I was asked by Marriott Traveler to design three infographics illustrating the best neighborhoods in each of three very different American cities: Chicago, Orlando and New Orleans. Words by Lisa Lubin, Jason Ferguson and Wayne Curtis.

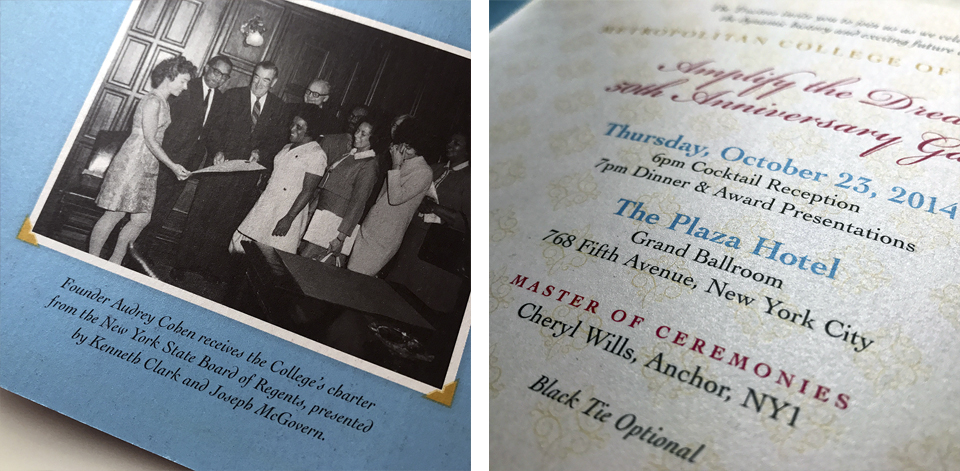

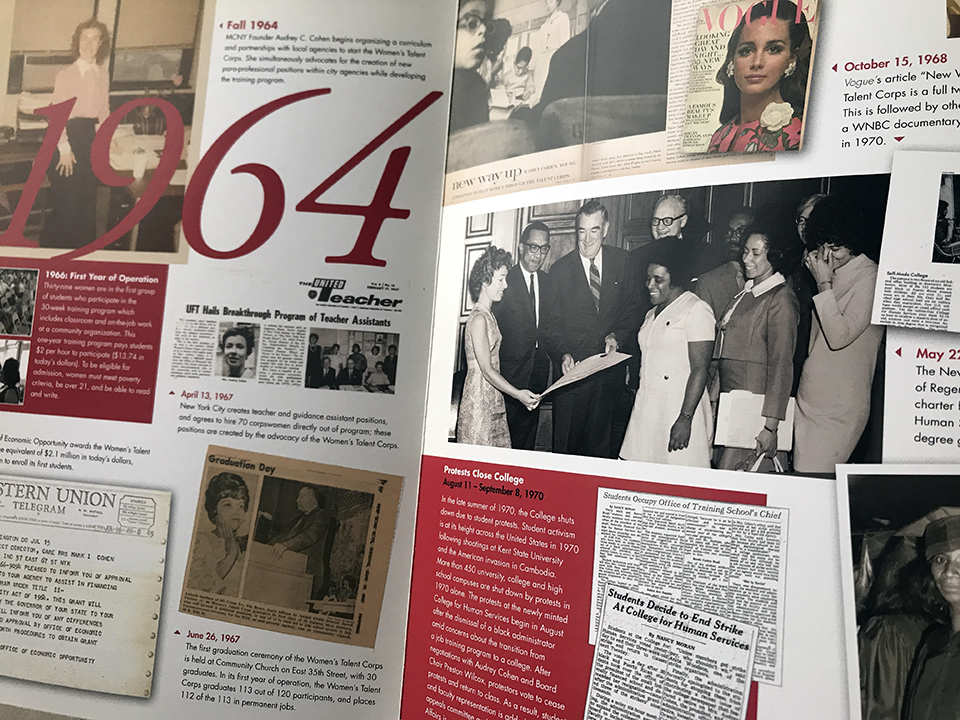

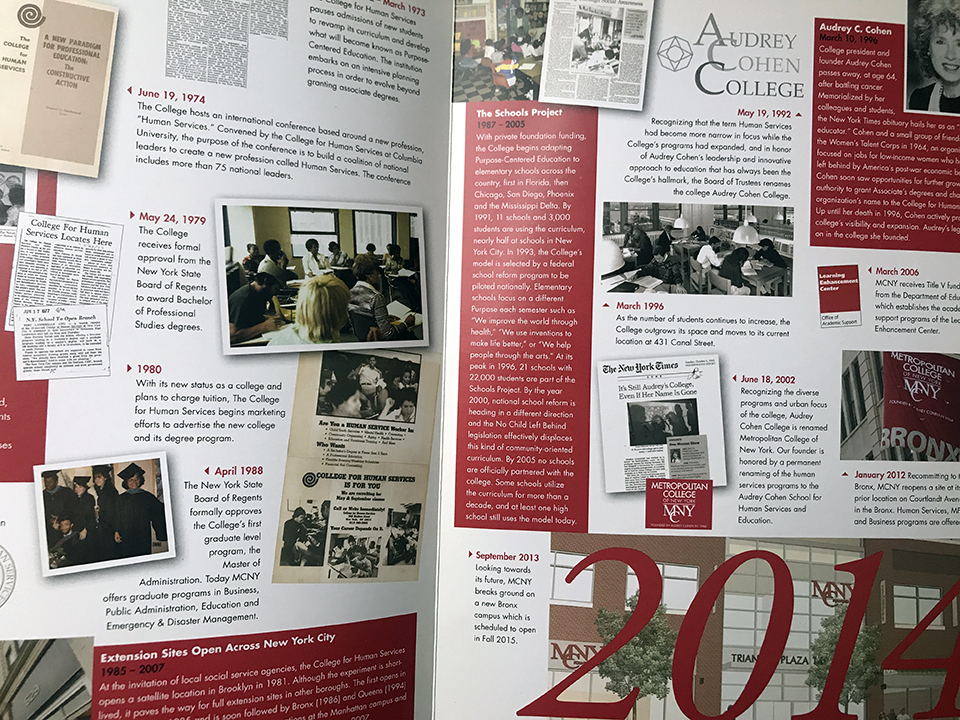

Founded in 1964 by education pioneer Audrey Cohen, the Metropolitan College of New York celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 2014 — as Senior Designer at Creative Source I was tasked with branding the college’s upcoming milestone. This began with designing the anniversary logo to be used on all marketing and high-profile advertising campaign across the city. This branding was expanded to the college’s invitation and event materials for its 50th Anniversary Gala at the Plaza Hotel. By far the most ambitious task was the creation of an interactive timeline illustrating the college’s remarkable history from 1964 to the present day. Installed on a fifty-foot wall at its Canal Street campus, the giant frieze incorporated photos, graphics, archival material and newspaper clippings, which were presented alongside significant news events overt the past half-century. A condensed printed version of the timeline was then mailed to donors and alumni. At the same downtown location, I designed a series of large-scale window decals at the same location, which advertised MCNY’s anniversary to pedestrians and motorists at street level.

I recently had the privilege of being interviewed by Vancouver-based designer Jon Rogers. Together with two fellow Canadians — his brother, former professional footballer Mark Rogers, and Vancouver Whitecaps commentator Peter Schaad — Jon has recently launched a new site called Footy Soldiers.

Read the full interview here.

Listen to the Footy Soldiers show here.

Check out Jon Rogers’ gorgeous work here.

I was recently interviewed by Chicago-based writer James Patrick Gordon for a profile on Paste Magazine. While the feature centers on my work and love of football, the thoughtful Mr. Gordon seemed keen to seek out the deeper, underlying themes behind what makes me tick:

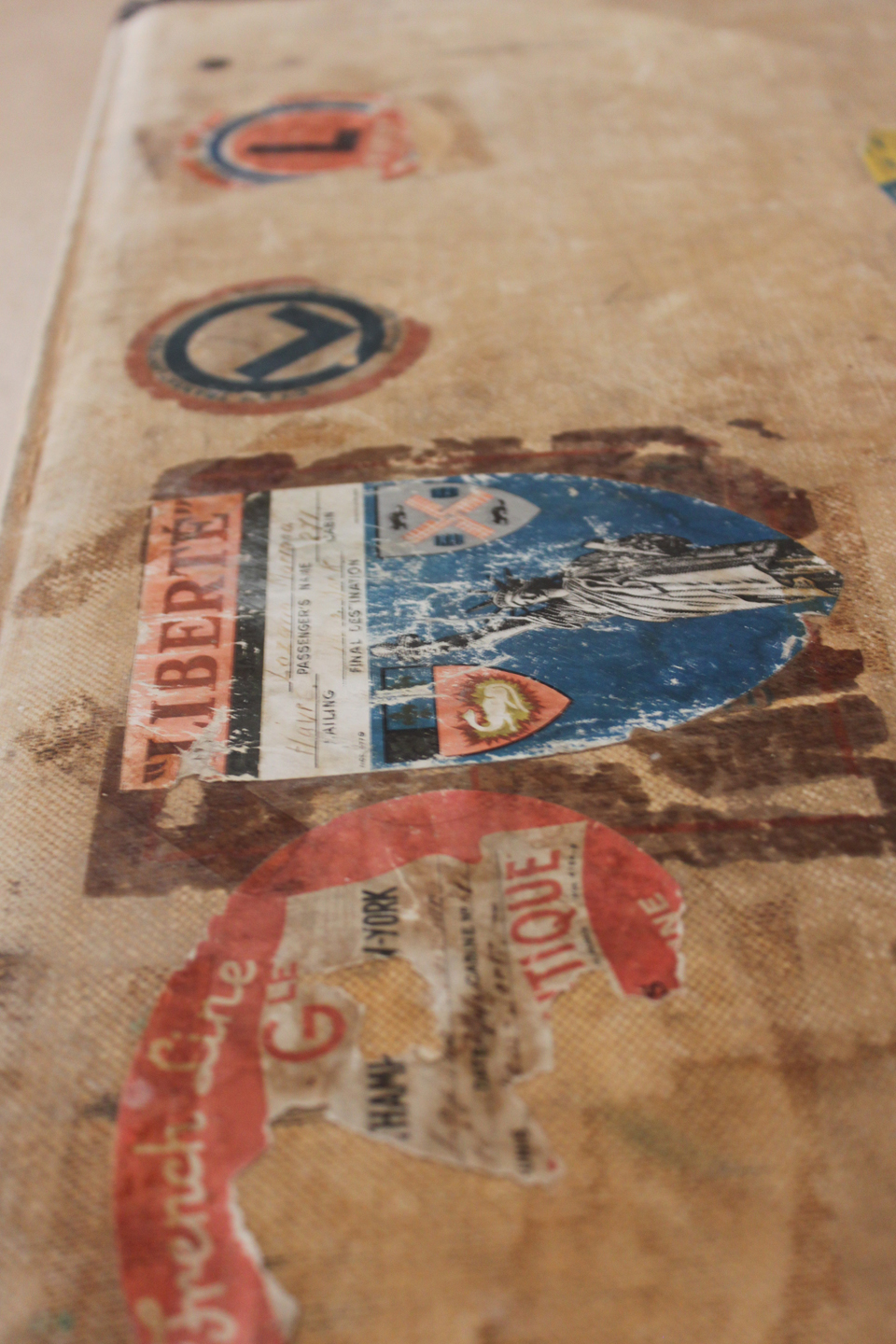

Looking at his work, Taylor’s images and writings form a kind of love letter to the beautiful game, one you discover hidden away in an old box in the attic decades later, perhaps long after you and the other party in your affair had parted company. It summons joy and melancholy and fading memory. Perhaps the word that best describes Taylor’s designs is saudade, a Portuguese lacuna that means either “longing for an absent other” or “nostalgia for a future that never happened.”

What Gordon says makes sense: I was born on January 30, which is the Brazilian day of saudade. So if you want my ruminations on football, music, and design and much more in between go ahead and click right here.

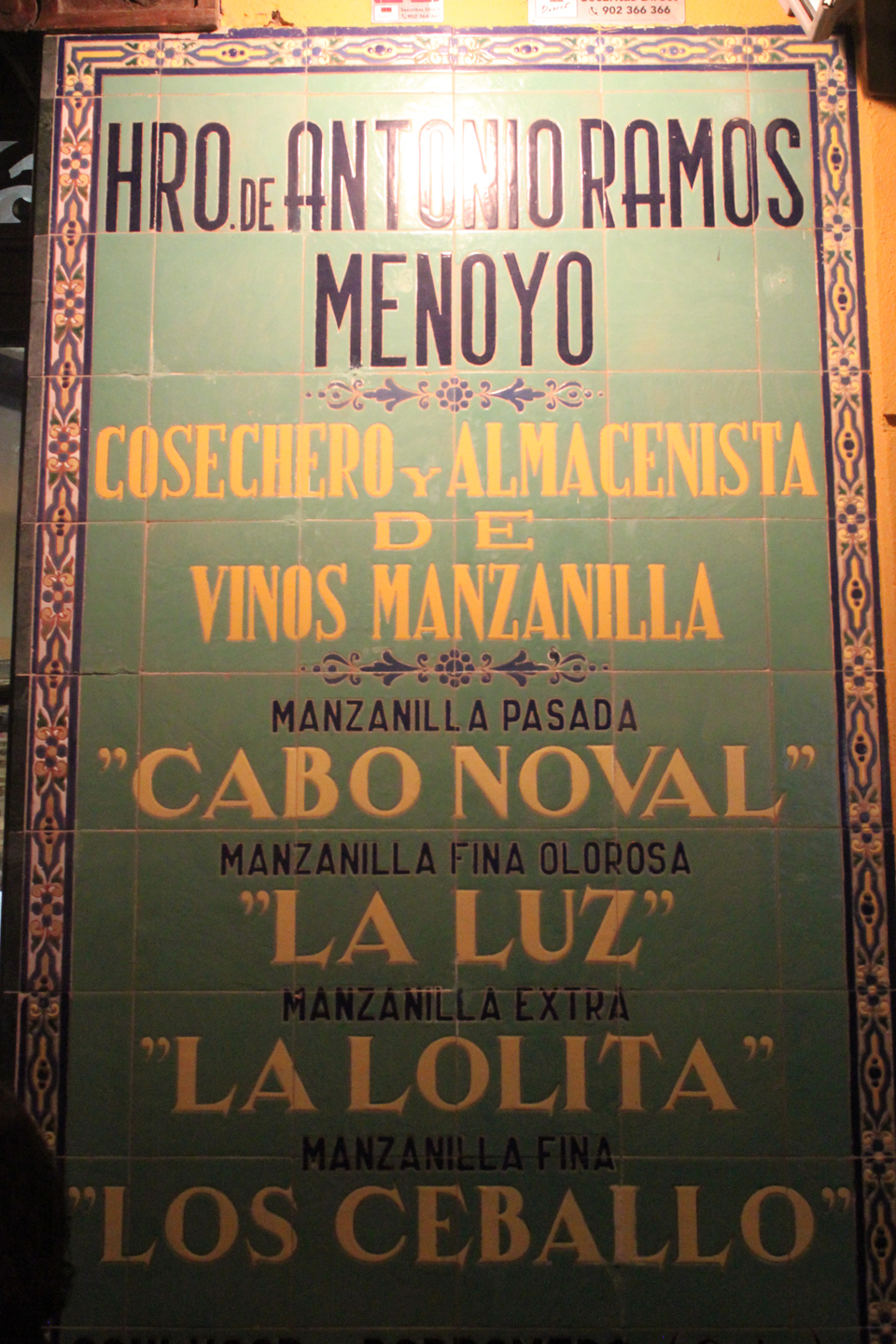

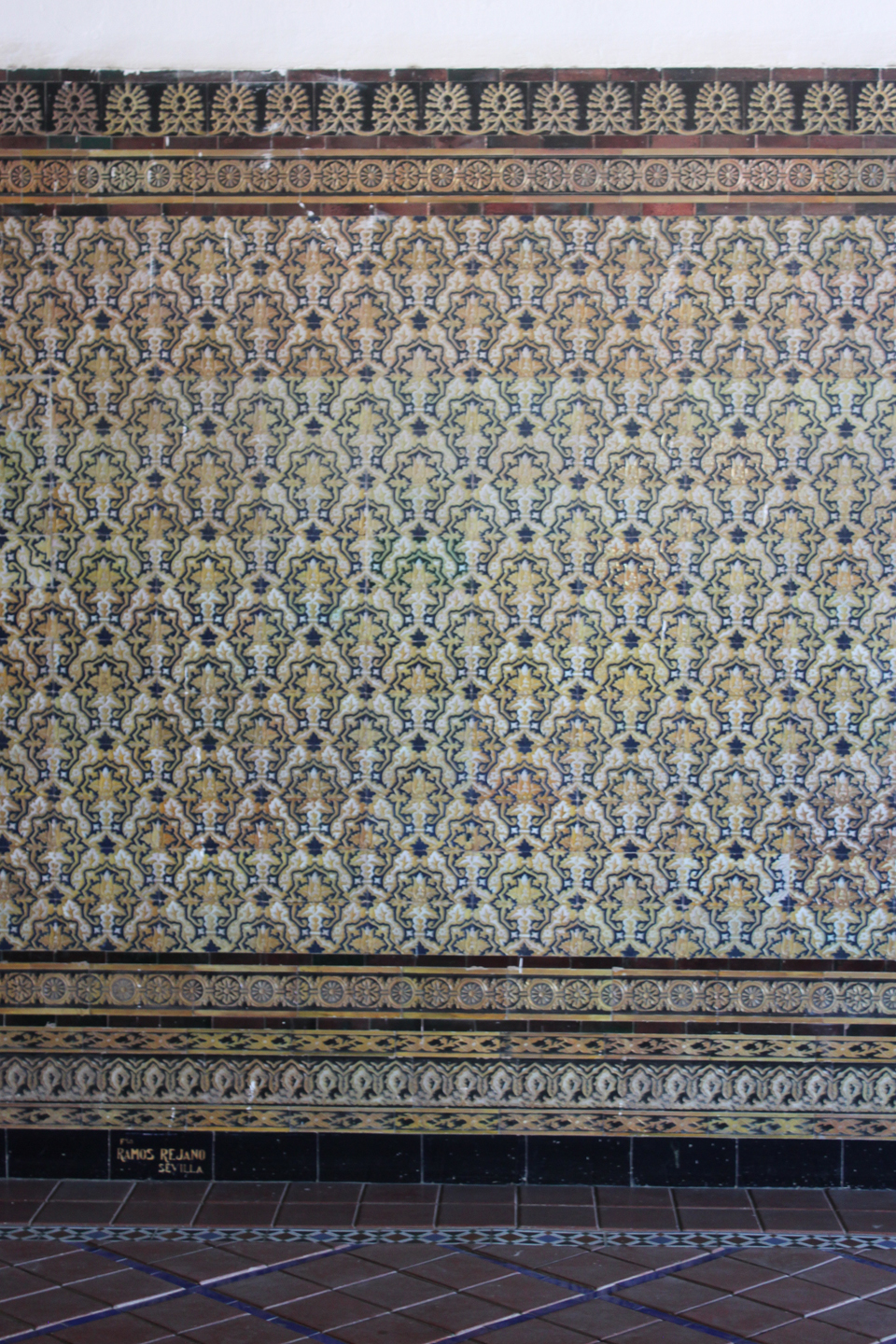

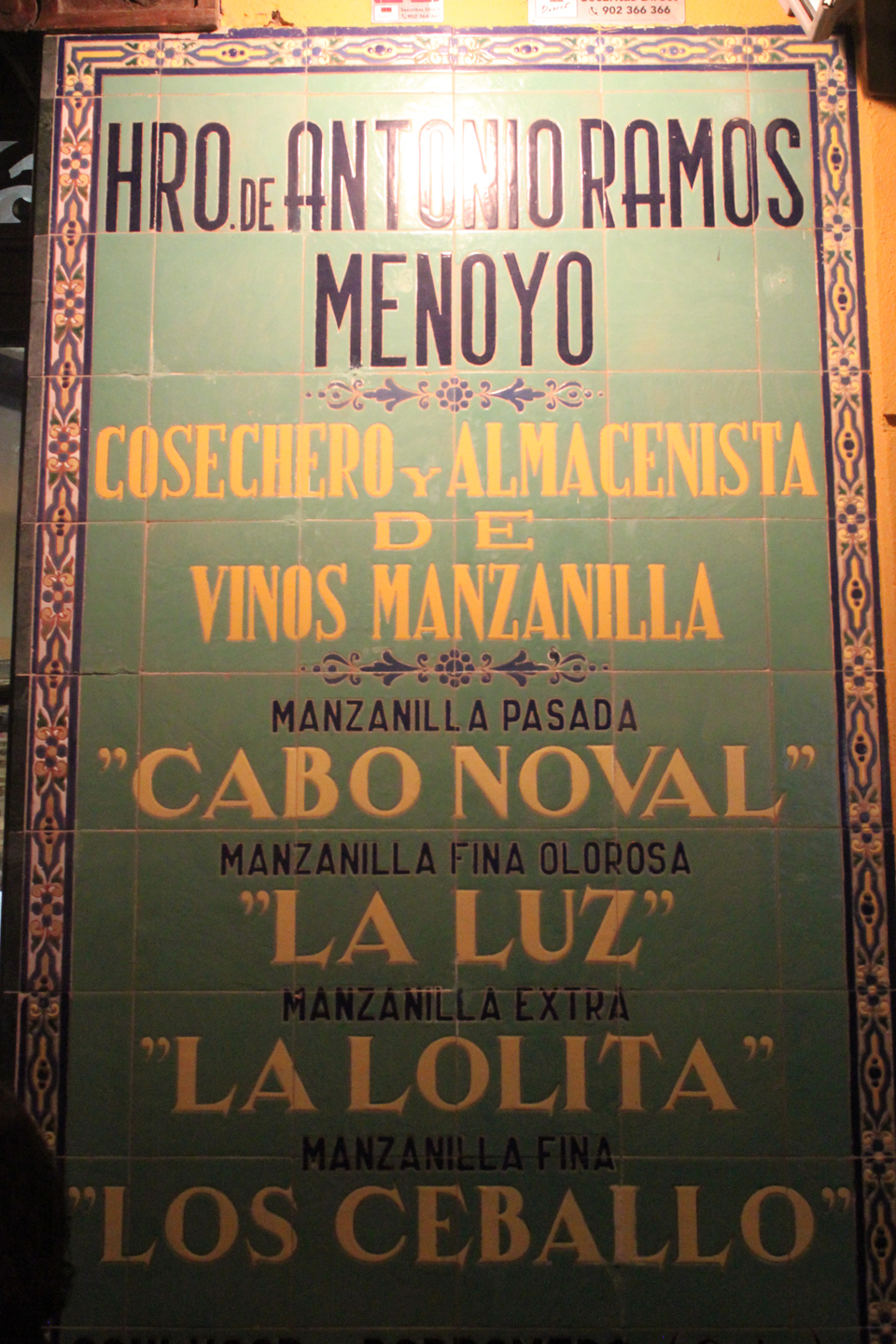

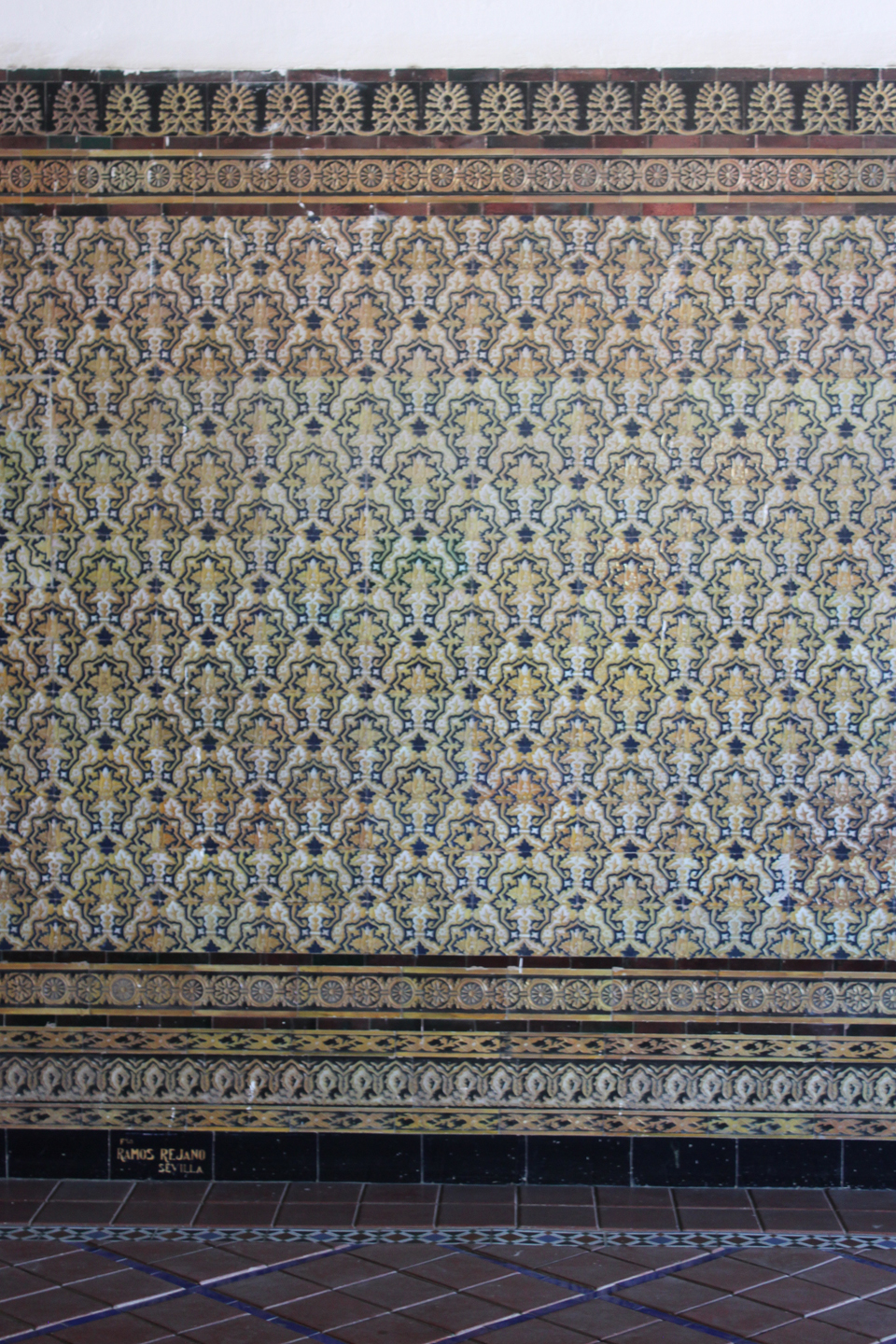

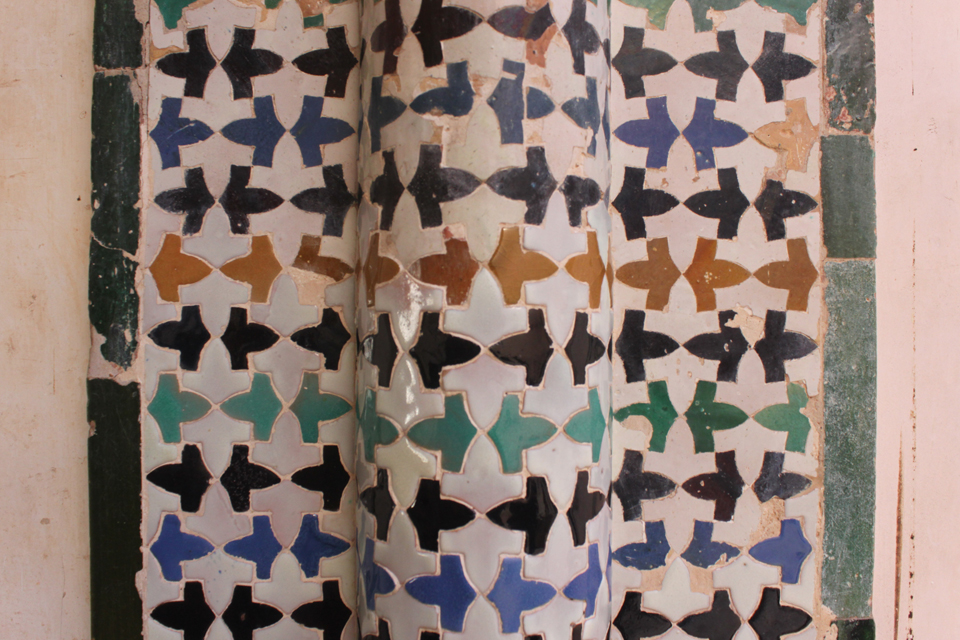

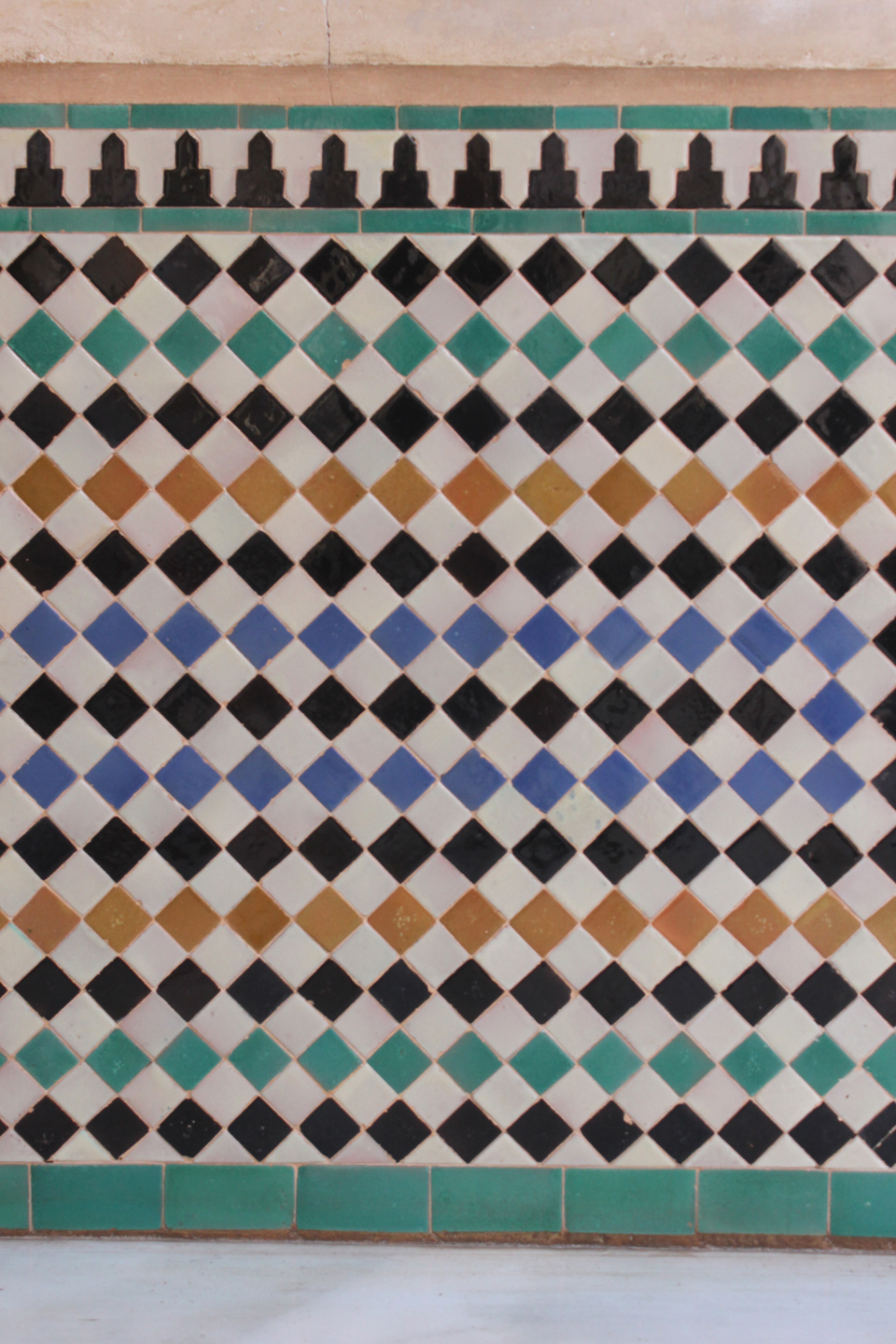

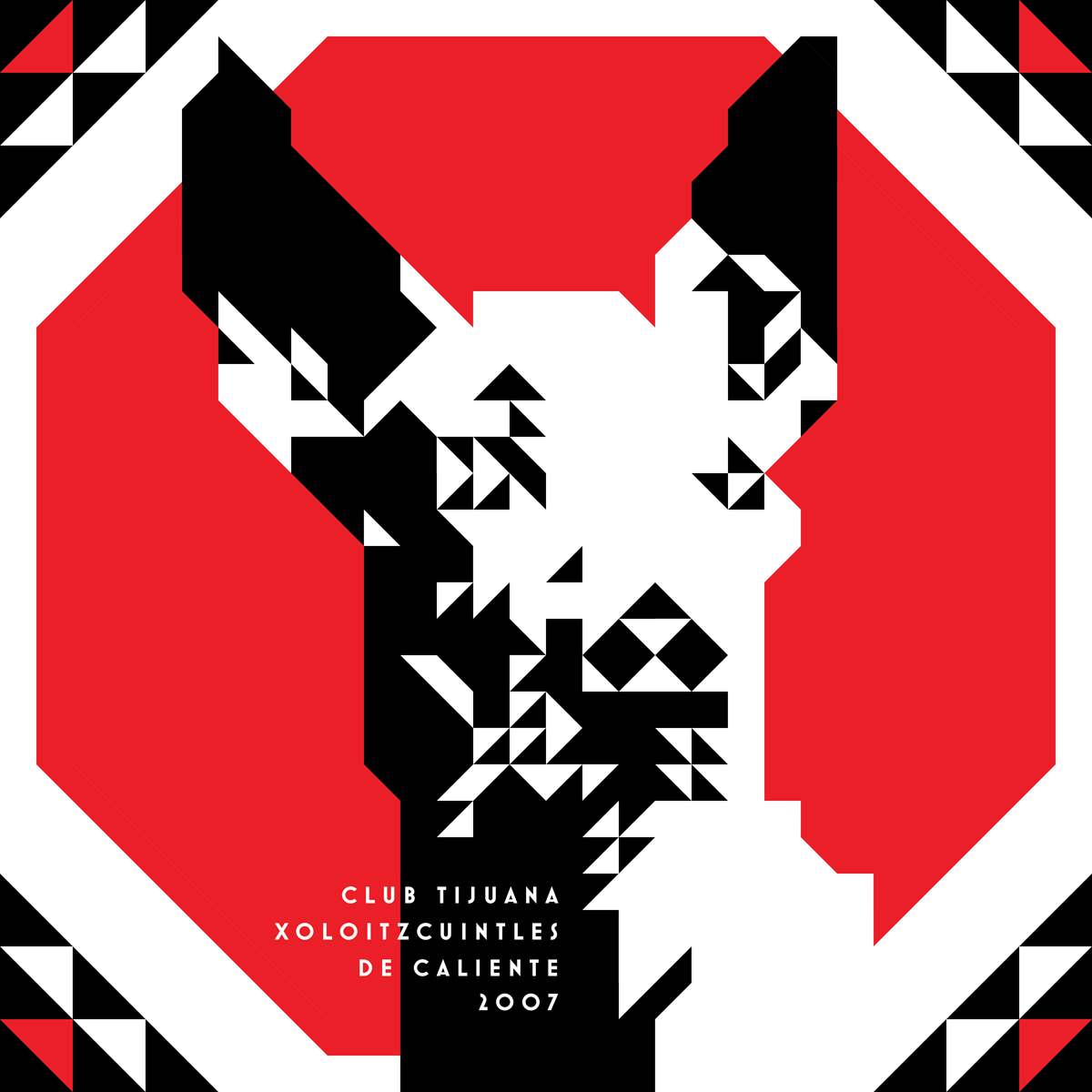

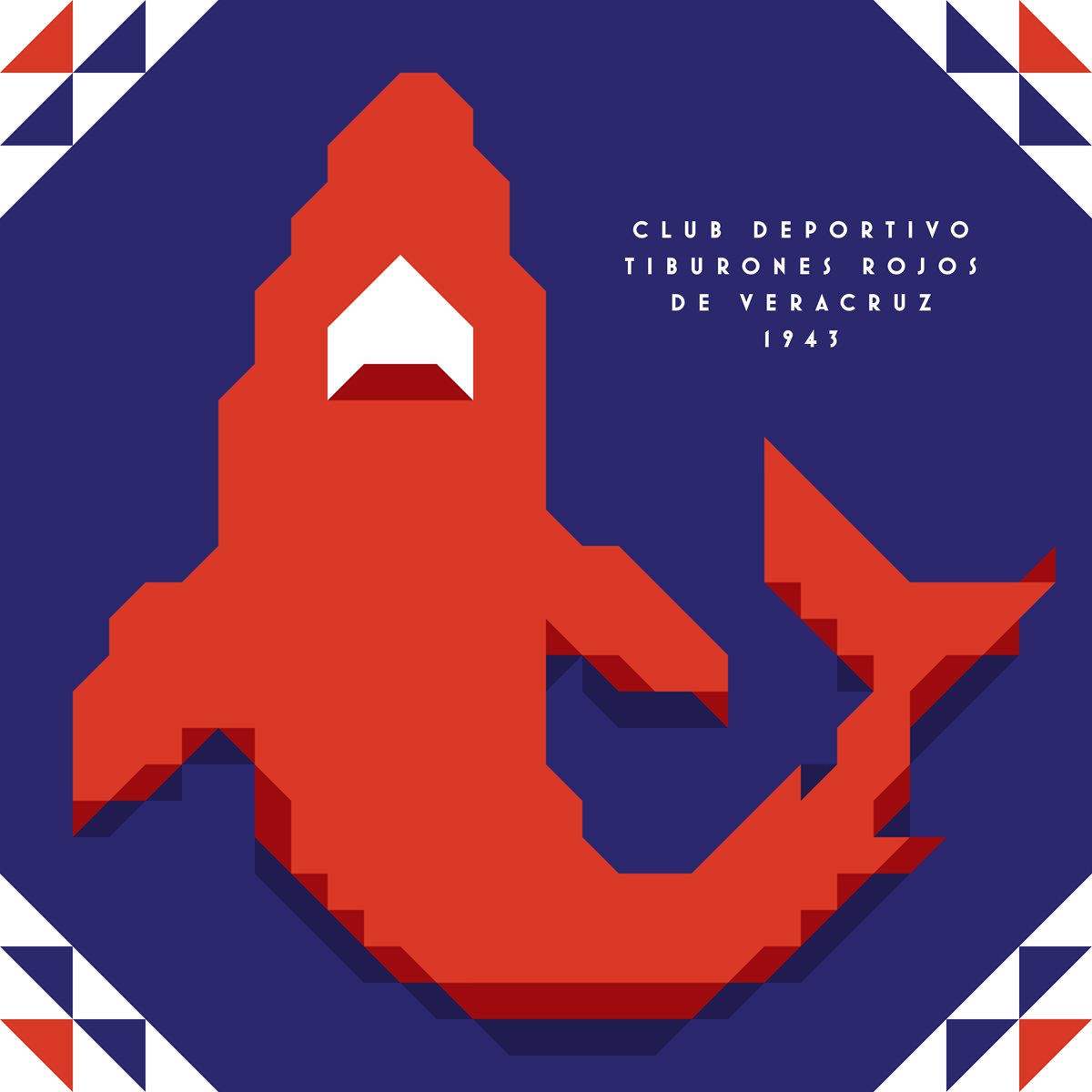

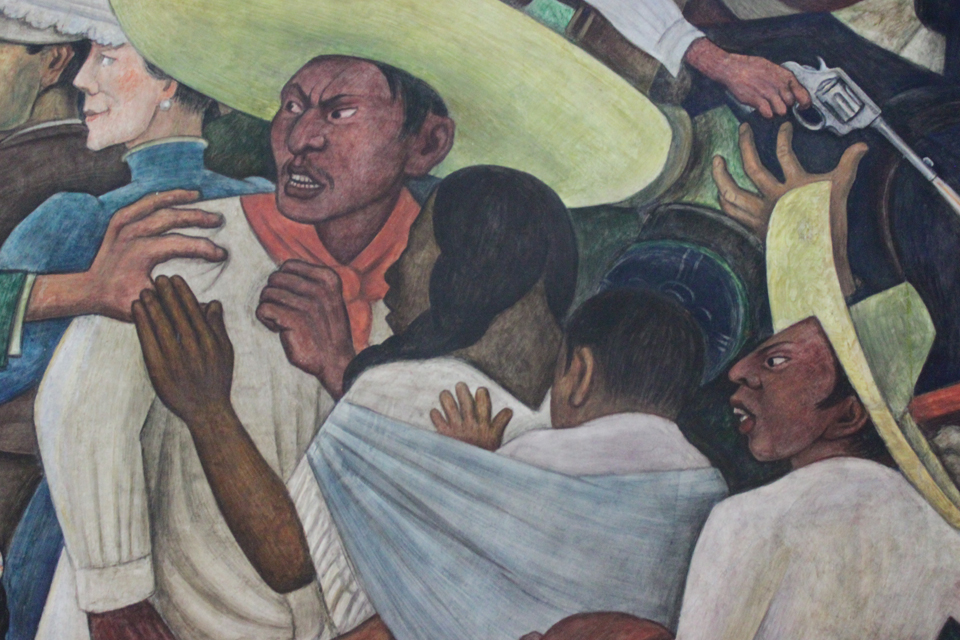

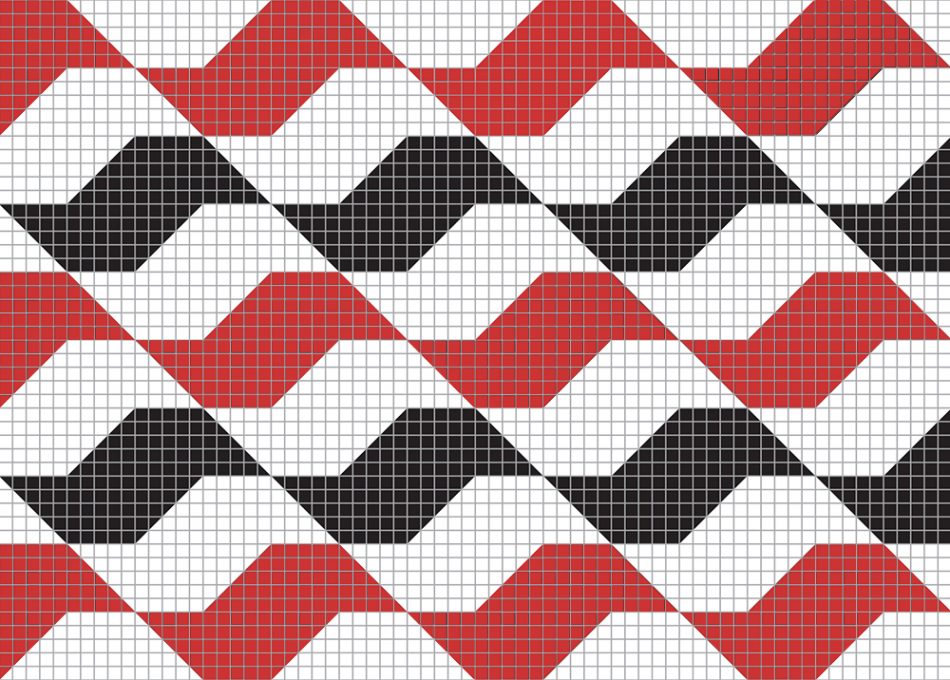

Geometric vector designs inspired by football teams, mosaics and floor tiles of Mexico. Each pattern is made entirely from triangles measuring just 36 x 36 pixels.

Club América 0-0 Puebla F.C., 24th January 2015.

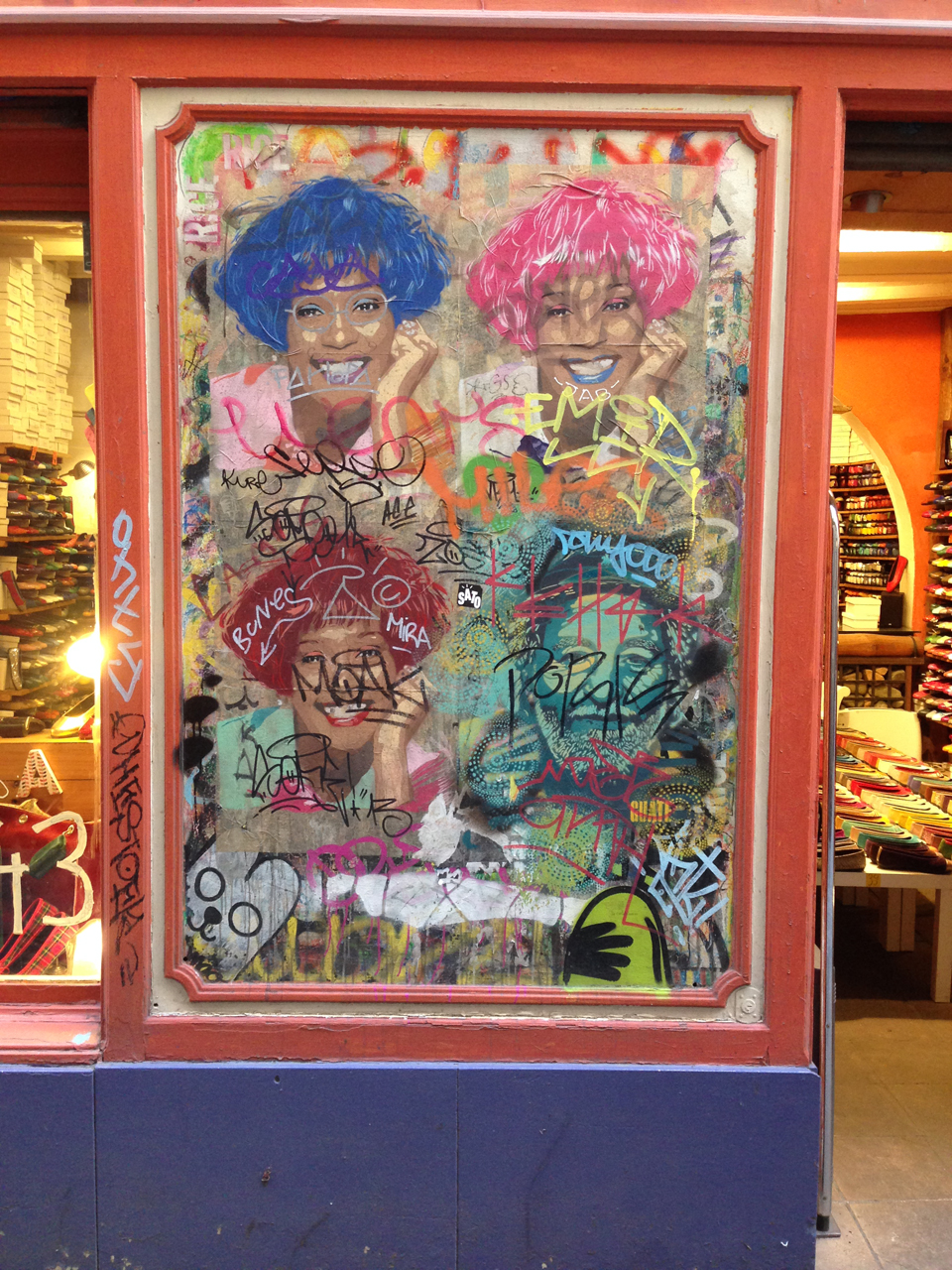

Mexico City, January 2015.

An afternoon at the Estadio Azteca

“REALLY? You don’t say!” Evidently our sarcastic taxi driver doesn’t need to be told where to take us — my unmistakeable mid-eighties Club América jersey is a glaring enough clue. We climb in to the back of his Nissan on the edge of Parque España; moments later we are heading south down Nuevo Léon, our destination the Estadio Azteca, where América is hosting Puebla in week three of the Liga MX’s Torneo Clausura.

Calz de Tlalpan is a wide highway leading to the vast forested borough of the same name. Unfortunately it is also susceptible to Saturday afternoon match-day traffic. I watch carriages of home supporters whiz past aboard the Treno Legero that runs parallel to the road. Meanwhile our car has become a stationary blue dot on my iPhone navigation app. I begin to regret not choosing public transport, but our driver assures us that we’ll make it in time for kick-off, which is less than twenty minutes away. I remain skeptical but I’m comforted by the site of more fans packed into cars and buses gridlocked alongside us, none of whom appear as nervous as me.

Pro-América graffiti tells me we must be getting closer, which our driver quickly confirms. “We’re now entering Aguilas country,” he explains, referring to the club’s most common nickname, as we pass dozens of street vendors selling giant yellow flags and blue novelty afro wigs. Suddenly, I glimpse part of the stadium’s roof out of the right window. Before I’ve time to take out my camera the car has come to a halt. “Here we are,” announces our driver, pointing in the stadium’s general direction. “El Coloso de Santa Ursula!”

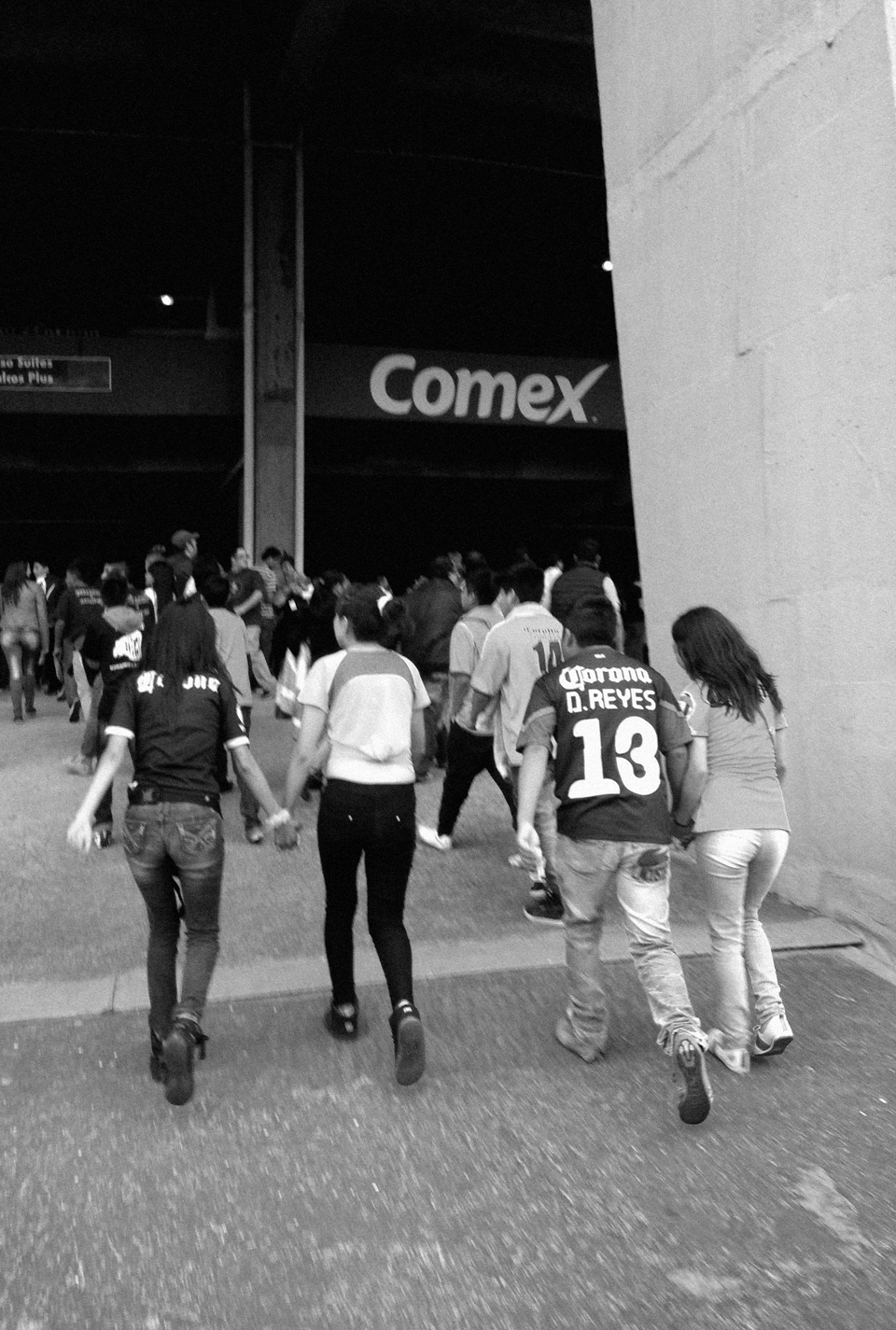

With kick-off nearing, I reluctantly ignore the array of stalls offering replica jerseys, more flags and various gold and blue trinkets. Almost immediately our path is blocked, and we find ourselves trapped behind a line of police officers, their riot shields positioned to form a human barricade. Thanks to the initiative of some quick-thinking Mexicans we are able to round this initial obstacle — the row of cops reacts by snaking into an L-shape but is too late to stop us passing. Once beyond the first blockade we become part of a larger crowd of ticket-holders that is are being prevented from entering through the stadium’s old-fashioned subway-style turnstiles. Five more officers perch awkwardly atop the entrance’s sloping concrete wall, one of whom shouts inaudible instructions through a megaphone which she has neglected to switch on. All of this takes place just feet away from Alexander Calder’s giant sculpture, Sol Rojo, which is now silhouetted in the late afternoon sun. Clearly this isn’t the standard procedure at home games, and the local fans’ confusion quickly turns to frustration, which fortunately is expressed through humour rather than violence. The chief source of entertainment is a middle-aged man in a Puebla shirt, who despite his allegiance keeps the crowd chuckling with a series of witty one-liners.

Clutching my ticket in one hand, my wife’s palm in the other, we squeeze through an increasingly impatient mass of bodies into the calm open space of the other side. Everything about the Azteca is as I’d pictured it, right down to the little stone wall at the base of the stadium’s perimeter. There is little time to marvel at the stadium’s exterior for the match has already started, and collective gasps of anticipation waft at intervals from inside the ground. I follow a group of excited young fans and attempt to fathom the ground’s foreboding outer skeleton, a mid-century maze of sloping ramps and vast beams of concrete. The girl at the gate barely glances at our tickets as we push through a narrow opening and finally walk out into the arena directly behind the goal. Happily the score is still nil-nil, but I always notice that the match itself becomes almost secondary to the spectacle on special occasions such as these.

“Vaaaa-mos! Vamos Ameeee-ri-caaaa!” The home crowd is already in good voice, and I can barely hear the young attendant as he points us in the direction of Section 201, PAN-2, which stands for Platea Alta Norte. When we reach Row 3 a female attendant politely asks the family sitting in our seats to find room elsewhere. As I finally reach the vacant seat 13 a huge cold cerveza Victoria is thrust into my welcoming hand, which evidently can be ordered quite inadvertently simply by making eye contact with a man in a uniform a few rows below you.

Our seats are every bit as good as I’d hoped: we sit on the third row of the second tier, slightly to the left of the goal. Not bad considering our tickets were purchased two days before the match for a mere 125 pesos (around $8.50) each. To put that into some perspective, the last time I went to a match in England tickets cost £25 a head. And that was for a pre-season friendly at Leicester City — twelve years ago.

I choose not to dwell on that depressing thought and opt instead to marvel at my new surroundings. Designed by Mexican architects Pedro Ramírez Vázquez and Rafael Mijares Alcérreca and inaugurated in 1966 (the roof was added just in time for the ’68 Olympics), the Estadio Azteca quickly grew into arguably the most iconic football stadium of the late twentieth-century, during which period it became the first venue to host the World Cup final twice. It could be suggested that those two tournaments bookend the World Cup’s golden age. Indeed, so ingrained are those colourful competitions into football fans’ collective psyche that I’ve always considered the Azteca to be the World Cup’s unofficial spiritual home, a notion reinforced by it having witnessed the trophy lifted by the game’s two most revered stars: Pelé in 1970 and Diego Maradona in 1986. If I were to ever lift the World Cup trophy myself (a dream that dims a little more with each passing year) I certainly can’t think of a place I’d rather be.

From my privileged vantage point I begin to replay the Azteca’s most memorable moments from those two sun-drenched tournaments. It quickly dawns on me that all the goals that immediately spring to mind were scored at the closest end to us, just feet from where I now sit. Gianni Rivera’s winner for Italy in their 4-3 extra-time semi-final victory over West Germany (a match referred to as “El Partido del Siglo” on a commemorative plaque outside the stadium) and Carlos Alberto’s famous fourth goal for Brazil in the final; Manuel Negrete’s spectacular scissor kick for the hosts against Bulgaria in 1986, Gary Lineker’s second against Paraguay, Maradona’s two goals against England (the Hand of God and the “Gol del Siglo”), his two oft-overlooked strikes against Belgium, as well as Jorge Burruchaga’s late winner against West Germany in the final.

Football stadia have changed a lot since then, some beyond recognition. Wembley has been demolished and rebuilt in recent years, while the modern Maracana bears little resemblance to the stadium that managed to contain 200,000 spectators for the 1950 World Cup final. Many of the world’s top clubs now play at new, corporate-funded arenas. In this regard the Azteca is no different. The stadium is now owned by Grupo Televisa, while vast banners displaying sponsors’ logos are rigged to the roof. The off-white benches that once lined the Azteca’s terraces have recently given way to proper seating, whose colours have been arranged strategically so when the ground sits empty the logos of Coca-Cola and Corona — the same logos that are emblazoned across the chest and shoulders of both teams’ shirts — span the entire stand. Of course, these aspects are invisible when the stadium is full, and I’m pleasantly surprised to find that the only other significant change since ’86 is the addition of two large video scoreboards at either end.

Just below the scoreboard at the top of our tier congregate América’s most hardcore supporters. A wire fence separates them from supposedly “casual” fans, although judging by their incessant chanting and fervent waving of yellow flags the only thing on their mind is to have a good time (and hopefully pick up three points along the way). A small pocket of away fans is nested high in the opposite end of the stadium, surrounded by helmeted police.

So far neither set of supporters has had anything to cheer about. América, captained by Mexican international Paul Aguilar, is dominating possession and creating plenty of early chances. The home side has seen some new arrivals since winning the Torneo Apertura in December. Among these is Colombian winger Carlos Darwin Quintero, who looks particularly lively. His defence-splitting pass finds another fresh signing, crew-cutted striker Dario Benedetto, who drags a shot beyond the far post. Moments later the Argentine gets on the end of compatriot Rubens Sambueza’s dinked cross and head goalwards, only for Puebla goalkeeper Rodolfo Cota to pull off the first of many excellent saves. Oribe Peralta is next to come close to scoring, racing onto Quintero’s low centre only to fire wide from inside the six-yard box. Before half-time the Mexican international spurns an almost identical opportunity, but this time his shot rebounds off Cota, onto his shins and out of play.

In honour of the home team’s nickname — Aguilas — an eagle is unleashed into the arena during the interval. The giant bird performs a couple of airborne laps of the stadium before swooping down into the centre circle and into the arms of its trusty handler. With the half-time entertainment out of the way, a stadium announcer now attempts to further warm up the crowd by conducting fans in cries of “Vaaamosss! Vamos Am-eeeeerr-iii-ccaaa!”

Early in the second half América’s Uruguayan coach Gustavo Matosas makes three substitutions in quick succession. The third of these — youth team forward Carlos Camacho — wears the number 101 shirt, which is the first time I’ve ever seen a player wearing three digits on his back. The team soon shifts into a higher gear and searches for the opening goal with relentless tempo. Quintero seems to be involved in everything from his advanced position on the right wing. First, his deep cross is met by Benedetto, whose angled header forces Cota to change direction and palm the ball to safety. Moments later, he receives the ball from a corner and shoots from a tight angle, only for Puebla’s rock solid goalie to parry.

Puebla’s forays into the opposition half are as cautious as they are infrequent, their five-man defence appearing more content to deny the Mexican champions from getting on the scoresheet. América are unfortunate not to break the deadlock on 75 minutes. Benedetto picks up a stray cross on the left and pulls the ball back for Quintero. The Colombian takes a touch to evade Orozco’s challenge before bending a right foot shot that rebounds off the outside of the post.

As the sun sets on the Azteca the sky above us turns a warm shade of pink, creating a dramatic backdrop. The closing minutes of the match are played out inside a now floodlit stadium, and the home fans’ restless anxiety becomes quite palpable. With neither side having found the net the loudest roar of the afternoon is reserved for the entrance of substitute Cuauhetémoc Blanco. Though the veteran international now wears the colours of Puebla, the local fans have clearly not forgotten the fifteen years he spent at the Azteca, and he is welcomed into the game with a rapturous reception fit for a local hero. A survivor of the 1998 and 2002 World Cups, the 42-year-old has clearly lost a little pace and gained a little weight in the ensuing years. Yet his arrival finally sparks life into the away side. Blanco’s cameo performance of positive runs, clever passes (most memorable of which is an audacious 25-yard no-look backheel inside his own half) and all-round creativity constitutes Puebla’s best spell of the match.

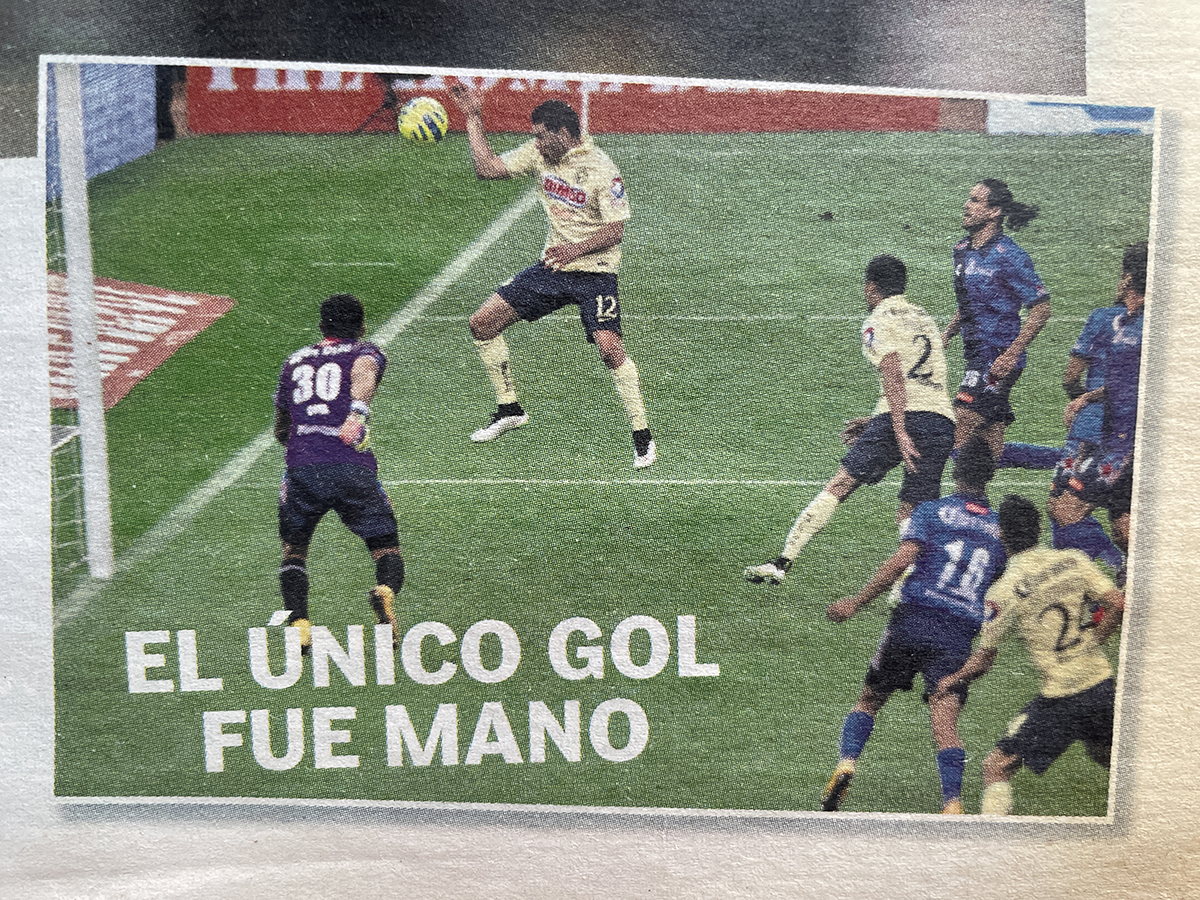

América struggles against its re-energized opponents for the next ten minutes, and the crowd starts to finally show its frustration, resorting to a chorus of deafening whistles. A late chance is presented in stoppage time, when a free-kick is won over on the near touchline. Sambueza swings in a deep and inviting cross. The other Aguilar — Pablo — meets the ball at the far post and looks set to score. But rather than nod home a certain winning goal, he opts to fist the ball into the Puebla net. Though the central defender’s technique would have received high praise had he been spiking a winning point on the volleyball court, from where we’re sitting the foul is plain to see even without the aid of a replay. The referee immediately rules out the goal and does not hesitate to show the culprit a second yellow card.

What compelled Aguilar to use his hand to score into the same net into which Diego Maradona had been assisted by the “Hand of God” 28-and-a-half years earlier? The irony of the situation is not lost on me, and I’m compelled to believe that some strange footballing variety of cosmic force must have been at play. Aside from the infringement itself, the two incidents bear no resemblance to one another — for a start Maradona got away with it! But where Diego jumped speculatively to intercept Steve Hodge’s lobbed backpass, Aguilar was the recipient of a cross aimed towards him. And while the little Argentine would not have reached the ball ahead of Shilton had he not used his left hand, the Paraguayan could have just have easily met the ball with his head. Instead his unnecessary actions instantly recall one of the Azteca’s most infamous moments, and in a bizarre way I feel privileged to have witnessed it.

The disappointment of wasting the chance and losing a man in such circumstances is a blow from which neither the team nor fans recover, and an entertaining match ends goalless. Having lost their previous match at Tijuana, today’s final whistle signals América’s second successive match without finding the net. In no hurry to bring an end to the occasion, we remain seated and watch as the stands empty, slowly revealing the giant logos of America’s chief sponsors. The hardcore home fans are still penned in their section by rows of police, and exiting the stadium proves a more straightforward task than entering had two hours earlier. Once outside we pass a life-size bronze statue of an unknown footballer. There is no plaque to identify him nor his creator, and according to even official sources his origin is a mystery. Maybe they should call him Pablo.

Liga MX Torneo Clausura 2015

Estadio Azteca, Mexico City

23 Moisés Muñoz, 2 Paolo Goltz, 6 Miguel Samudio (101 Carlos Camacho 64′), 12 Pablo Aguilar, 22 Paul Aguilar (17 Ventura Alvarado 62′), 3 Darwin Quintero, 5 Cristian Pellerano, 11 Michael Arroyo (10 Osvaldo Martínez 55′), 14 Rubens Sambueza, 9 Dario Benedetto, 24 Oribe Peralta. Coach: Gustavo Matosas.

30 Rodolfo Cota, 4 Facundo Erpen, 16 Michael Orozco, 26 Mauricio Romero, 7 Luis Noriega, 18 Luis Esqueda, 19 Flavio Santos, 22 Freddy Pajoy (10 Cuauhtémoc Blanco 78′), 28 Francisco Torres, 11 Matías Alustiza (29 Wilberto Cosme 45′), 21 Luis Gabriel Rey (24 Sergio Pérez 73′). Coach: José Guadalupe Cruz.

Referee: César Arturo Ramos Palazuelos (Culiacán, Sinaloa).

Bookings: Noriega 5′, Samudio 27′, Romero 33′, Goltz 66′, Esqueda 81′.

Sent off: Pablo Aguilar 91′.

Attendance: 62,300.

See more of my photos from the Estadio Azteca here.

Playacar, Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo, Mexico, January 2015.

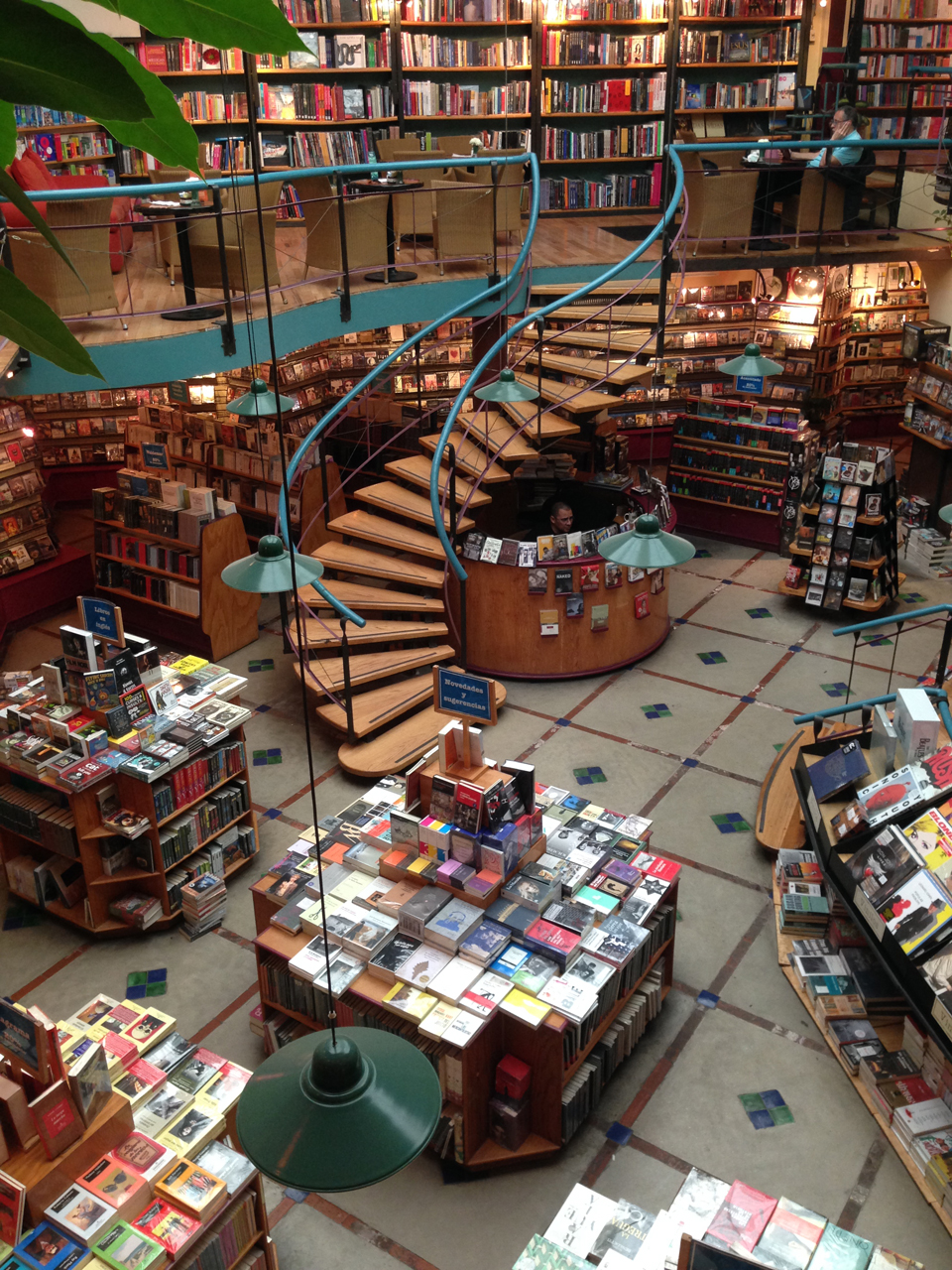

Barcelona, January 2016.

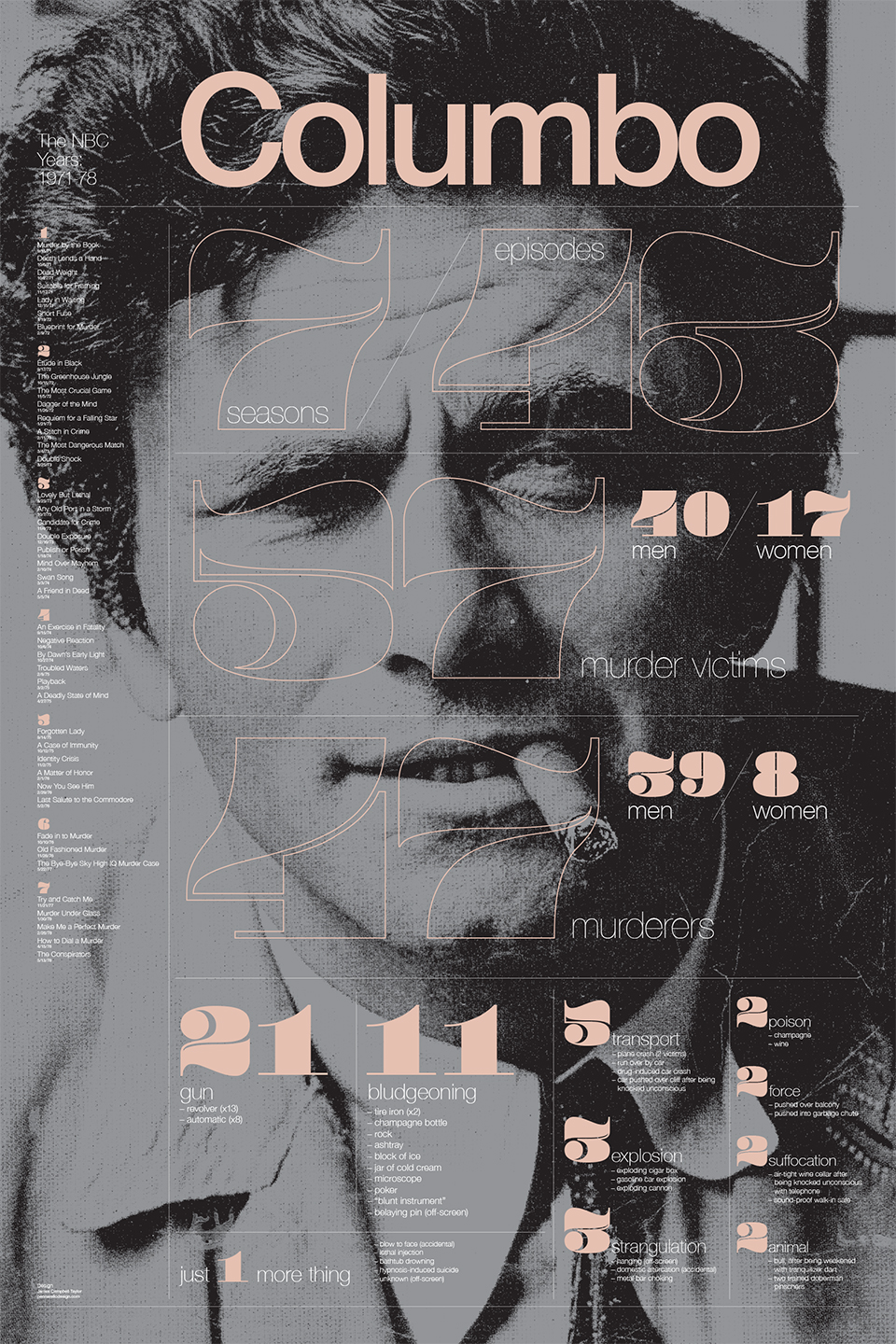

Infographic celebrating everyone’s favorite rumpled LAPD detective, Lieutenant Columbo, famously portrayed by the late Peter Falk.

My Columbo obsession began quite innocuously one Sunday evening last August, when I happened to stumble upon the episode “Étude in Black”, starring John Cassavettes and Blythe Danner. It was the first time I’d seen the show since I was a child, but I enjoyed it so much the next day I was excited to discover that the show’s first seven seasons (originally aired on NBC from 1971 to 1978) were available to stream via Netflix. And so naturally I decided to watch every episode in sequence, a marathon task that I finally completed in November.

Artwork celebrating the 80th Anniversary of São Paulo Futebol Clube. The design is based on the familiar bird-like shape that appears throughout the city of São Paulo, most famously on some of its mosaic sidewalks. While a symbol of the city, the silhouette itself is a graphic interpretation of the shape of São Paulo state. The individual tiles depict some of the great players who’ve represented the famous club, while the horizontal red and black stripes are a reference to the team’s home shirt.

Prints, t-shirts and pillows(!) of this design can be purchased here.

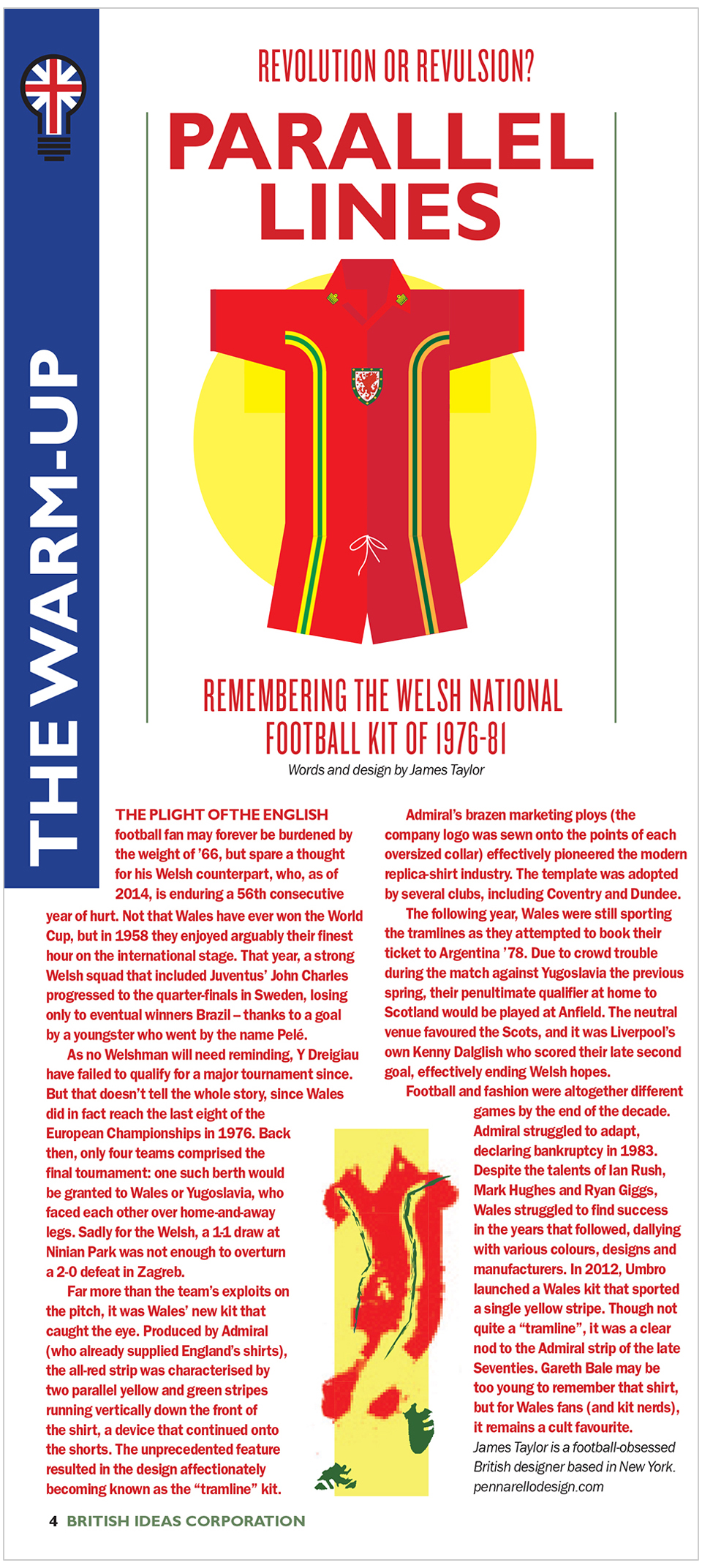

If you happen to be in northern Wales this weekend you can be among the first to get your hands on a special preview issue of British Ideas Corporation. Devised by GQ writer Lee Gale, the magazine will be launched at Festival No. 6, a three-day music event taking place in the picturesque town of Portmeirion. My contribution consists of a brief profile (with accompanying graphics, of course) of the Welsh kit of the late-70s, a football shirt no less hideous than it was innovative (see below). Portmeirion was the setting for the cult 1960s TV series The Prisoner starring Patrick McGoohan, from whose lead character the festival takes its name. This year’s edition features a diverse line-up of pop notables, including Beck, Pet Shop Boys, Kelis, Peter Hook, Neneh Cherry… not to mention Motown legends Martha Reeves & The Vandellas! Look out for the official launch of British Ideas Corporation in March 2015. And remember, it doesn’t matter what you wear, just as long as you are there…

Taste of Italy is an annual event held in Houston and organized by the Italy-America Chamber of Commerce of Texas (IACC). Now in its third year, Taste of Italy is the largest food and wine fair in the U.S. devoted exclusively to Italian wines and food products, producers, and gastronomic traditions. I was asked to create a new logo in time for the 2017 show, which will be applied to all communication and marketing materials at the event next March.