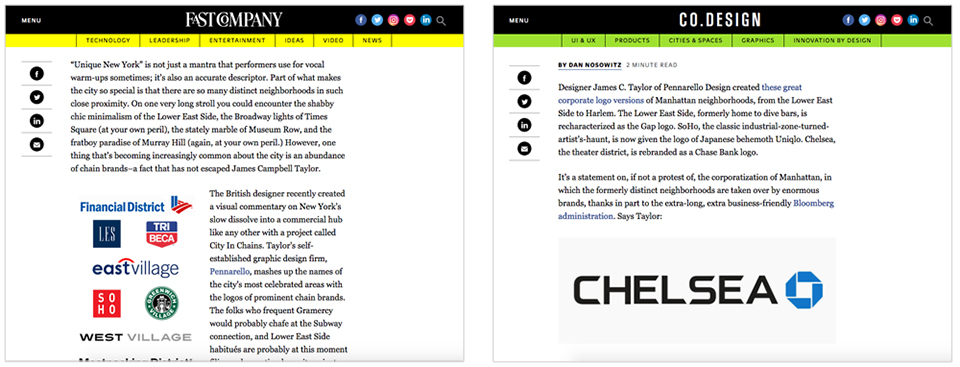

My “City In Chains” project was featured on Fast Company not once but twice this week! First in this Co.Create article by Joe Berkowitz; then in this Co.Design article by Dan Nosowitz. Both authors discuss the work as a commentary on New York’s shifting socio-economic landscape. Thanks guys!

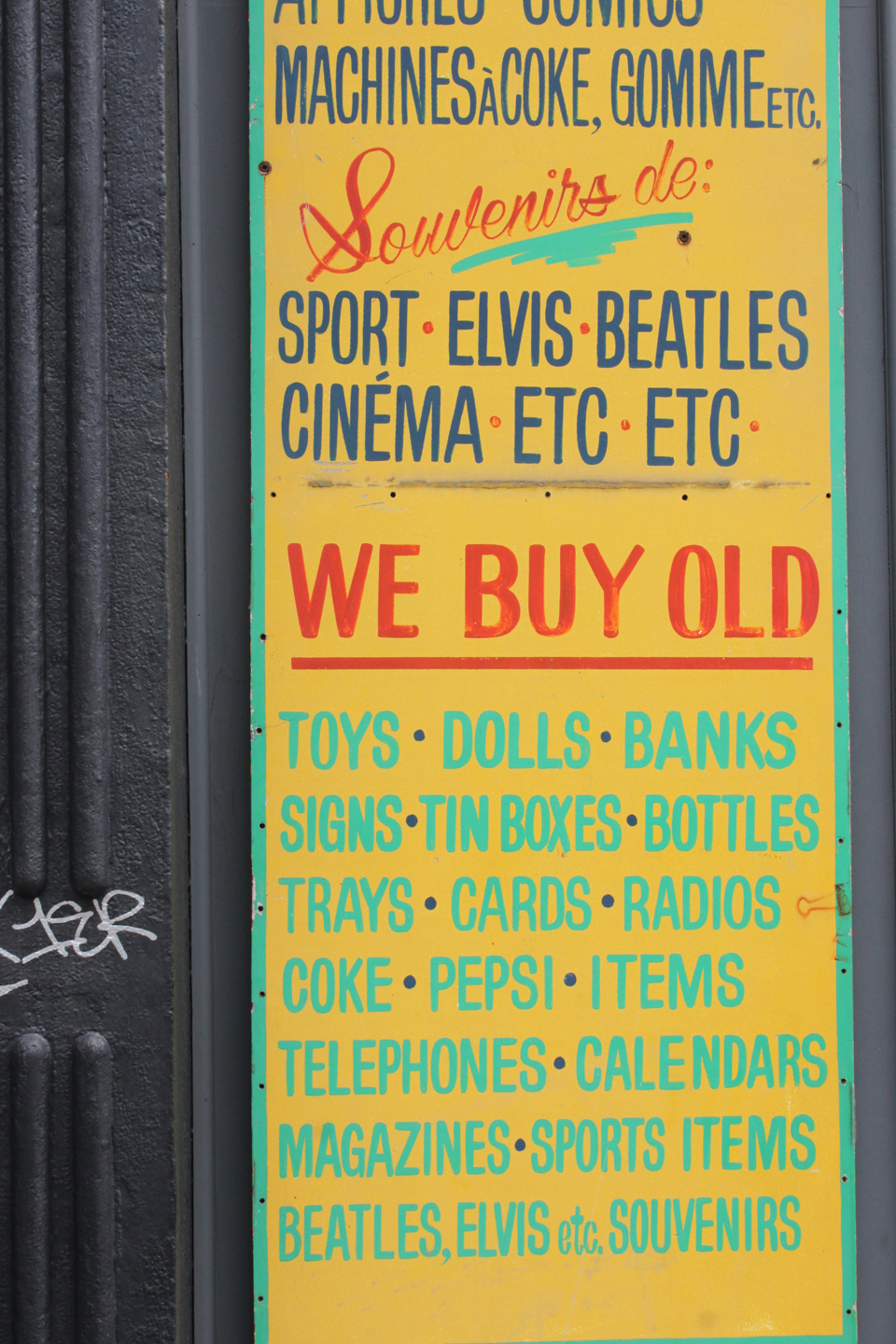

I originally devised this project in 2014 as a reaction to Manhattan’s rapidly changing retail landscape. It was both a fun design exercise that would also serve as a commentary on the unchecked corporate invasion on a city that once prided itself on its refusal to embrace suburban values. I recently updated the artwork to reflect the updated branding of some of the brands originally featured.

The Huffington Post

Fast Company blog Co.Create article by Joe Berkowitz

Fast Company Co.Design article by Dan Nosowitz

Dashburst article and interview by Lauren Mobertz

Design Taxi

Under Consideration blog Brand New

Mediabistro blog Stock Logos

Feel Desain

Mexican design blog, Paredro (en español)

PSFK

Downtown blog Bowery Boogie

Animal New York

Notes on New York

Killahbeez

Trend Hunter: Part 1 / Part 2

Show America

I was asked by The Huffington Post to comment on my “City In Chains” project. HuffPo calls the work “a bit sinister”, which I’m going to take as a compliment. Check it out here.

I designed this poster for a contest organized by Columbia Legacy through Creative Allies. The winning entry will be included in the forthcoming Miles Davis box-set, Miles at the Fillmore, a series of live recordings from the summer of 1970. If you like it you can vote for it here!

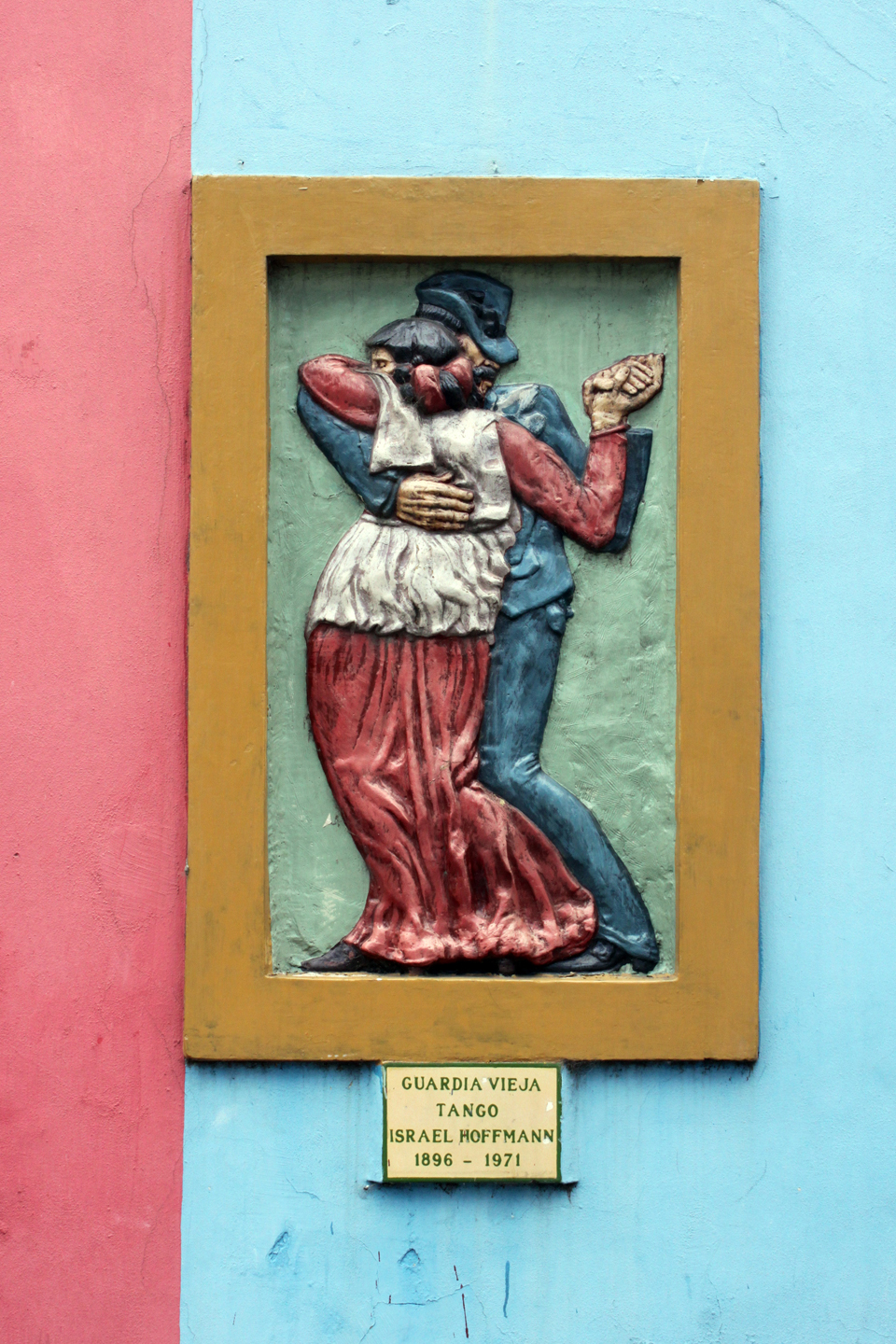

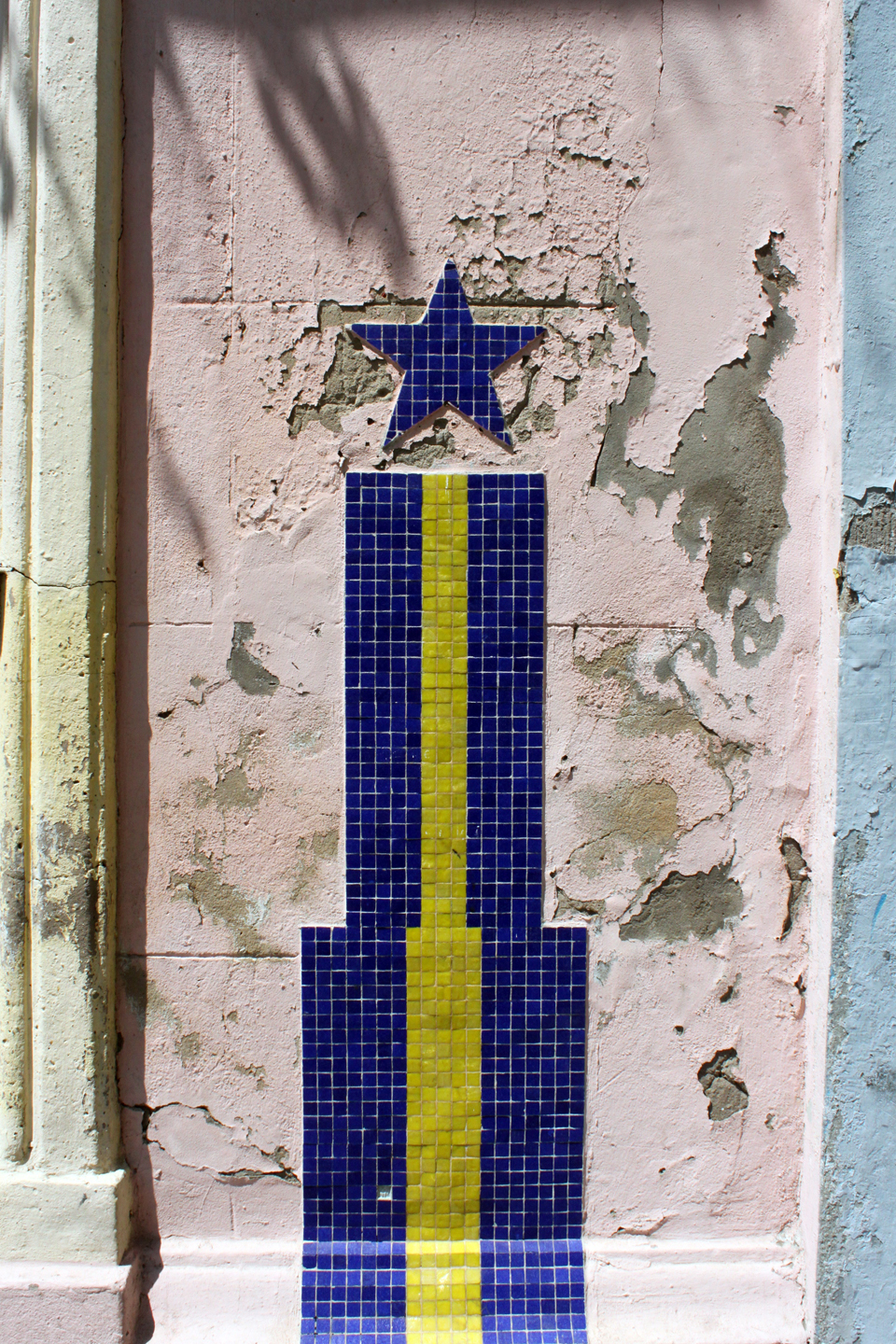

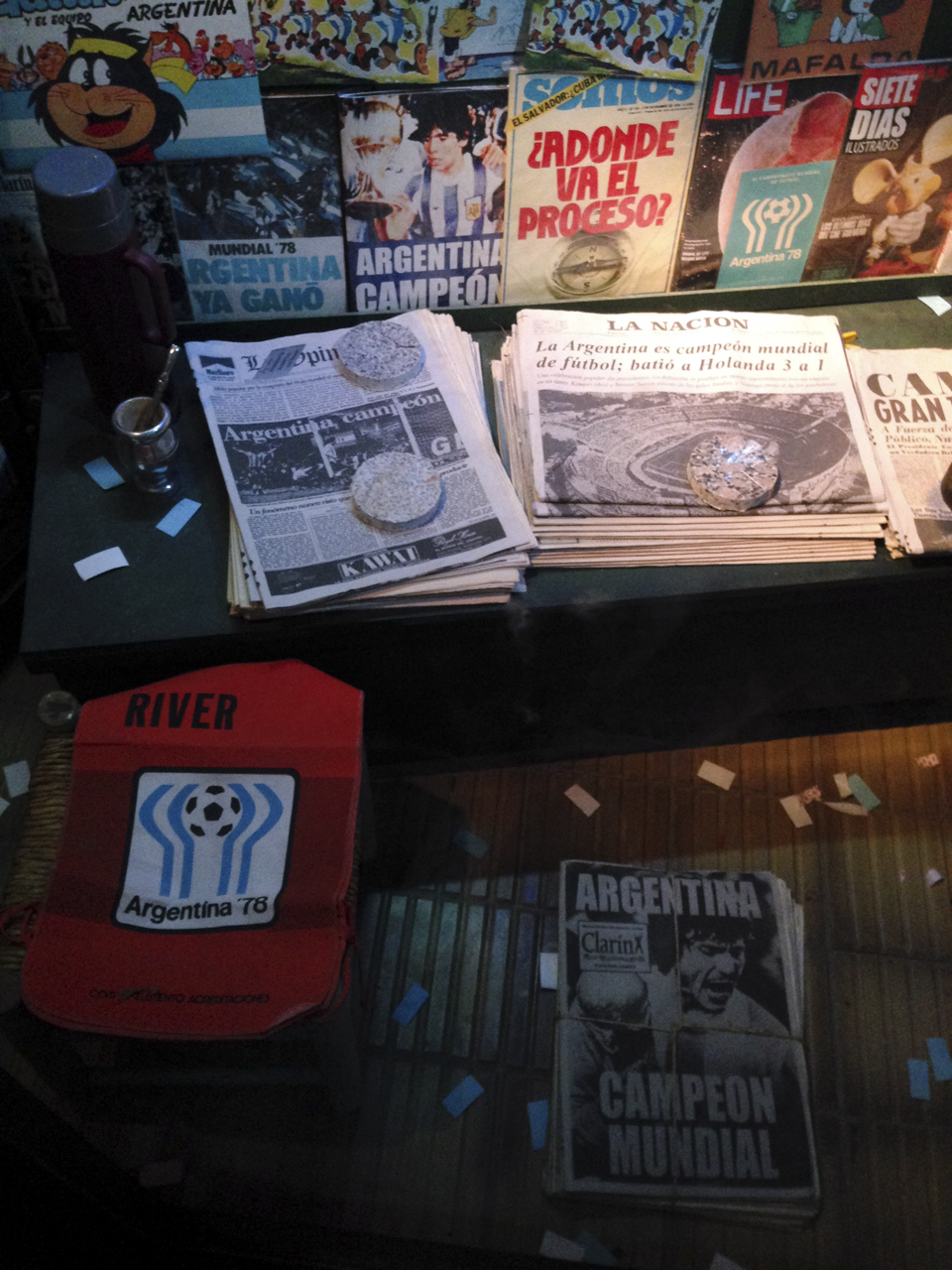

Buenos Aires, Argentina, January 2014.

My Metropolitana di Firenze project is featured in this month’s issue of The Florentine, Florence’s English-language newspaper. Read the full January 2014 issue here (turn to page 31).

1:00 a.m. When I awake there is no telling where I am. The last thing I remember is the sight of Manhattan’s white lights disappearing into the distance, then there was darkness. Fields, mountains, desert, sea — at this time of night they all look the same from the window seat. Gazing out at nothing but my own reflection, I am reoriented by a set of dotted headlights winding along an invisible road several thousand feet below me. The highway forks and splits again. Soon the route has multiplied into an elaborate network of light, a gasoline-fueled bloodstream whose main arteries all connect back to a pulsating heart: Los Angeles. Within seconds my view becomes a glowing expanse of electric orange that twinkles and stretches to the coastline, before slipping under the inky cloak of the Pacific. The 737 glides out over the ocean for what seems like a long time, then at last swings into a U-turn and touches down at LAX.

2:00 a.m. The flurry of passengers disperses from the carousel until only a handful remains. I have two hours to kill until my bus leaves, so I wander outside. It’s warmer than where I’ve come from but there’s a chill in the air. The soft rustle of swaying palm trees lining the road is interrupted every two minutes by a stern voice that reiterates the complex regulations of the arrivals area: “No parking, no waiting.” The voice follows me as I stroll back and forth between Terminals 1 through 4, wheeling my half-empty case behind me. Disappointingly I return to my starting point sooner than expected, so I repeat the journey, only this time at an even slower pace. On the second lap I locate a vending machine tucked away inside an alcove. I drop in seven quarters and the machine dispenses a packet of cookies so brittle they barely survive the fall. I perch outside on what passes for a bench and start snacking on tiny pieces of broken biscuit. At the other end a girl removes a ukulele from her luggage and begins to play, singing gently to herself.

4:00 a.m. I can barely make sense of the schedule, so the bus that shows up on time may or may not be there to take me to Union Station. I climb aboard anyway. In the front row two women natter to each other in Spanish; I sit one row behind them on the other side of the aisle. All the other seats remain empty. We leave the refuge of the airport behind as the bus makes its way tentatively through an apparently deserted city. Beneath the elevated road are side streets of two-storey buildings, drooping phone lines, the occasional parked sedan and not a pedestrian in sight. Moments later the bus is barreling steadily up Interstate 110 towards downtown L.A.’s small cluster of skyscrapers, already visible between the slender fan palms silhouetted by a pink and purple sky.

4:30 a.m. The bus drops me off in front of Union Station, which looks like an abandoned luxury gambling resort. I feel like the only person in California who isn’t at home in bed, until I reach the end of a long concourse where I’m approached by several men who haven’t been to bed in weeks, maybe years. I take refuge in a small convenience store where I ask the teenager behind the counter the best way to get to the Greyhound station, but the teenager behind the counter has no idea. The old part of the station is like a vast art deco cathedral, only not as welcoming. Dozens of large wooden armchairs — cordoned-off from non-ticketholders — sit empty, so I’m forced to stroll up and down the dark central aisle alongside the vagabonds and the homeless. A Hispanic man with kind eyes and a heavy blanket over one shoulder politely asks me if I can direct him to the Placita church. He says he’s not from around here, to which I apologize and tell him that unfortunately neither am I. Over near the Christmas tree a Desert Storm veteran asks me where I’m from. When I tell him he gives me a fist bump and wishes me a Merry Christmas.

5:00 a.m. I’d heard that the Greyhound station was even less desirable than the train station, but after an hour spent wandering in circles I decide to take my chances. I convince an idling taxi driver to take me; he agrees on the condition that once we get there I’m to go straight inside. We arrive five minutes later and I make a beeline for the front door without looking up. To my relief the waiting room is well-lit and packed: men, women, children, all in the same boat — soon to be bus — as me. I nibble on some more cookie scraps and wait on a bench made out of metal wire, which is precisely as comfortable as it sounds.

6:00 a.m. It’s still dark as the bus pulls out, but the glimpses I’m offered of the city at dawn are as fascinating as they are fleeting. Fatigue soon sets in, but I’m jolted awake when the bus makes brief stops in North Hollywood and San Fernando, by which time the day is beginning to break.

7:00 a.m. When I awake again the early morning sunshine has completed its morning ascent, and casts a long shadow of the speeding Greyhound across the desert floor. L.A.’s urban sprawl is long behind us, and my view is a barren landscape of crumbling brown rock under a deep blue sky.

9:00 a.m. Though its Spanish style houses and two-story Art Deco grandeur has clearly seen better days, downtown Bakersfield’s faded pastels look beautiful in a run-down, dusty sort of way. One can easily imagine a time not too long ago when dust was all there was around here. We pass the Fox Theater — a local landmark — and pull in at the Package Express. My brother-in-law picks me up in his Toyota. I’m told that spectacular mountains surround Bakersfield. Unfortunately the thick smog that pervades the city has rendered them all but invisible. Still, it’s nice to know they’re there.

9:10 a.m. We pull off the highway and continue down a long road, before eventually turning right. What follows is a swirling maze of streets lined with seemingly identical houses. Presumably the people inside them are all different. Each home appears to have been painted with the same array of colors, ranging from vanilla to parcel paper and comprising all fifty shades of beige that exist in between. This suburban splendor is disrupted by the addition of seasonal accoutrements carefully positioned in every front yard, and the site of a plastic red-nosed reindeer and a Peanuts nativity scene suddenly reminds me its Christmastime.

9:30 a.m. The car pulls up outside a house whose exterior is bereft of holiday ornamentation — perhaps so the owners can locate it more easily. The theme continues inside, where I’m welcomed and offered breakfast. Sleepy but for some reason still awake, I take my coffee outside, where the air is cool and still. I can now begin to make out the outline of the mountain range through the haze. I lie on an inviting slither of exposed lawn and wait for the sun’s distant warmth to reach me.

Los Angeles, Bakersfield and the Getty Center, December 2013.

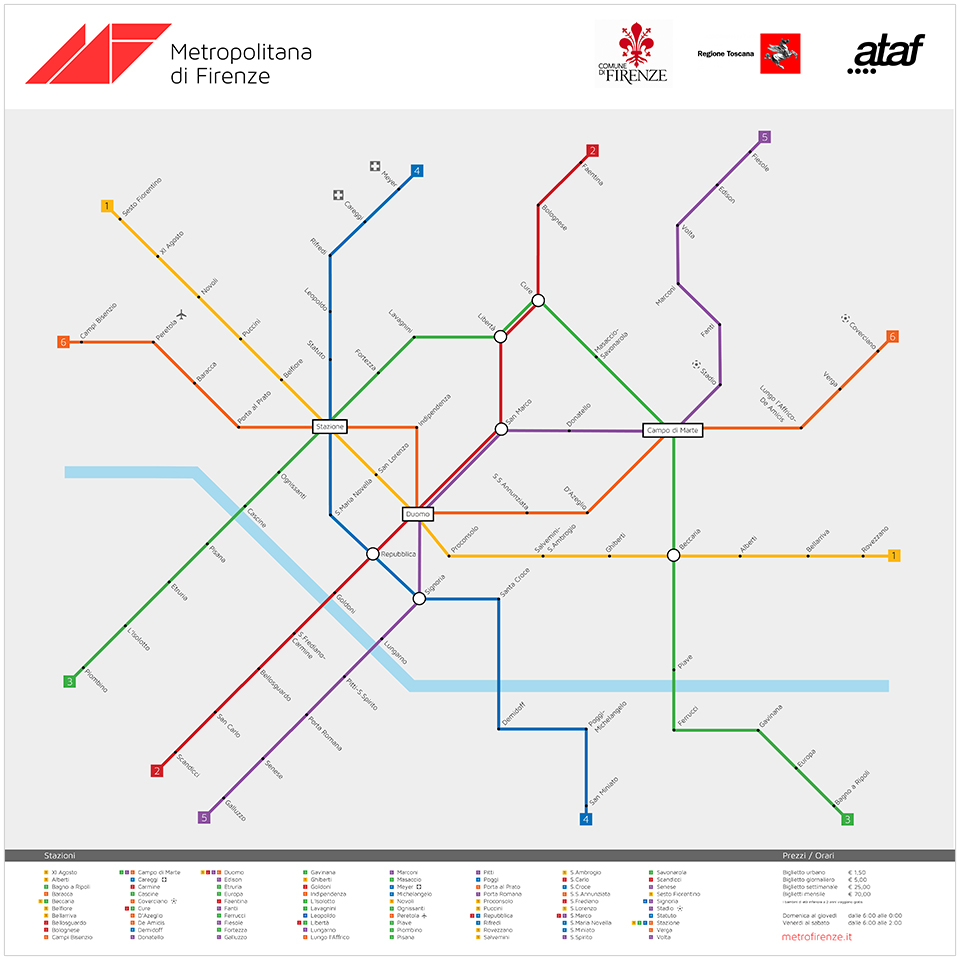

When I first visited Florence, in the summer of 1988, I was surprised to find that the city’s most famous square, Piazza della Signoria, had been reduced to little more than a gigantic hole in the ground. The purpose of this excavation was to unearth some of the myriad relics that lay below the surface of the piazza, but the project had become open-ended when archeologists discovered Roman baths, three churches, plus towers, streets, walls and cemeteries hidden beneath the city, all dating back centuries. Eventually a perspex floor was laid over their findings allowing pedestrians the chance to gaze into this forgotten world. The fact that such endless historical bounty sits just feet below one of the world’s most visited cities is a major reason why Florence remains the only major Italian city without a modern metro.

Years later, while living in Florence, I often recalled my first visit and sometimes wondered what was below the streets I now walked on daily. Which in turn led me to often ponder how different Florence might have been had it gone ahead with any of the several suggestions for an underground rail network put forward over the years. In 2010 Florence restored its tram service which had been closed down since 1958. The first line opened connects the suburb of Scandicci with the city’s main railway station, Stazione Santa Maria Novella. Work has since begun (belatedly) on one of three more projected lines, parts of which may be underground, leading some residents to opine that a genuine metro would have been a smarter long-term solution.

With this in mind, I finally decided to create my own hypothetical Metropolitana di Firenze, a project that has taken the best part of a year and forced me to branch outside the safe confines of the aesthetics of design and into the complex realm of public transport and urban planning. The first and most daunting task was to plot the network itself, something that posed a considerable challenge, and I soon realized how an inside knowledge of the working city is essential in order to even begin such an undertaking. I began by listing the city’s major points and drawing a rough map from memory, imagining the most useful locations for stations and the distances between them. The hardest part was plotting the actual train routes, deciding where they should start and finish without doubling up on other lines. Since Florence’s centro storico is relatively compact, I made sure each line connected an area of the city’s outskirts with its center; the same lines frequently interconnect with one another allowing passengers the flexibility to divert their own route. In my enthusiasm to cater to all residents in every part of town, I was ultimately able to service the whole city more than adequately with six lines, although Milan (3), Rome (2) and Naples (2) seem to get by with half as many.

With the possible exception of the London Underground, public transport logos are rarely memorable, which is why I deliberately kept this one fairly low-key. I wanted it to look like something that could have existed for several years without ever being considered for an update. That being said I wanted it to evoke aspects of Italian graphic design. The use of triangular shapes is a subtle nod to the Futurist movement which, in addition to being preoccupied with speed and technological advancement, is inexorably linked to Florence. I also chose a typeface that was clear and modern but not without personality. The logo is echoed throughout all of the metro’s printed collateral, creating a geometric window device which can be updated regularly to feature different images of the city. As is the norm for modern underground networks, tickets are swiped for entry and are available for a single-trip (€1.50), or as daily (€5), weekly (€25) or monthly (€70) cards.

The station platforms are highlighted with color-coded signage corresponding to the relevant line, while large wall-to-wall LCD screens project live footage of the street directly above, creating an ever-changing mural of light. Another twenty-first century innovation is the smartphone app, which allows travelers to plan their journey and learn the quickest route to their final destination. As I mentioned already, this project is solely hypothetical and admittedly unrealistic: the construction work alone for such a dense network would cause decades of disruption to thousands of people daily. I certainly do not expect Matteo Renzi to jump on the idea with any urgency. Rather, it is simply a self-assigned exercise to finally realize a concept that’s been floating around my head for about twenty-five years.

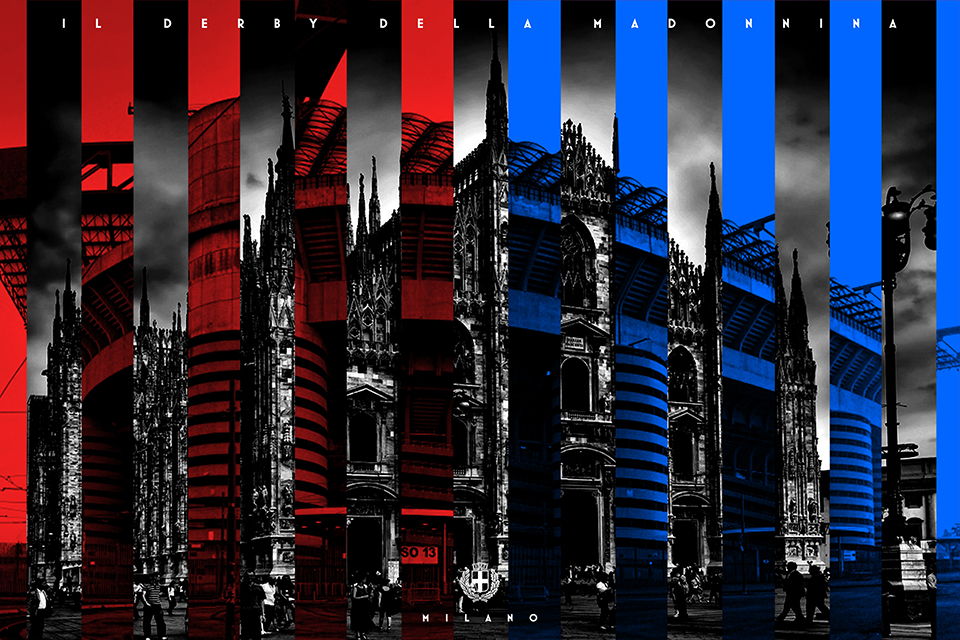

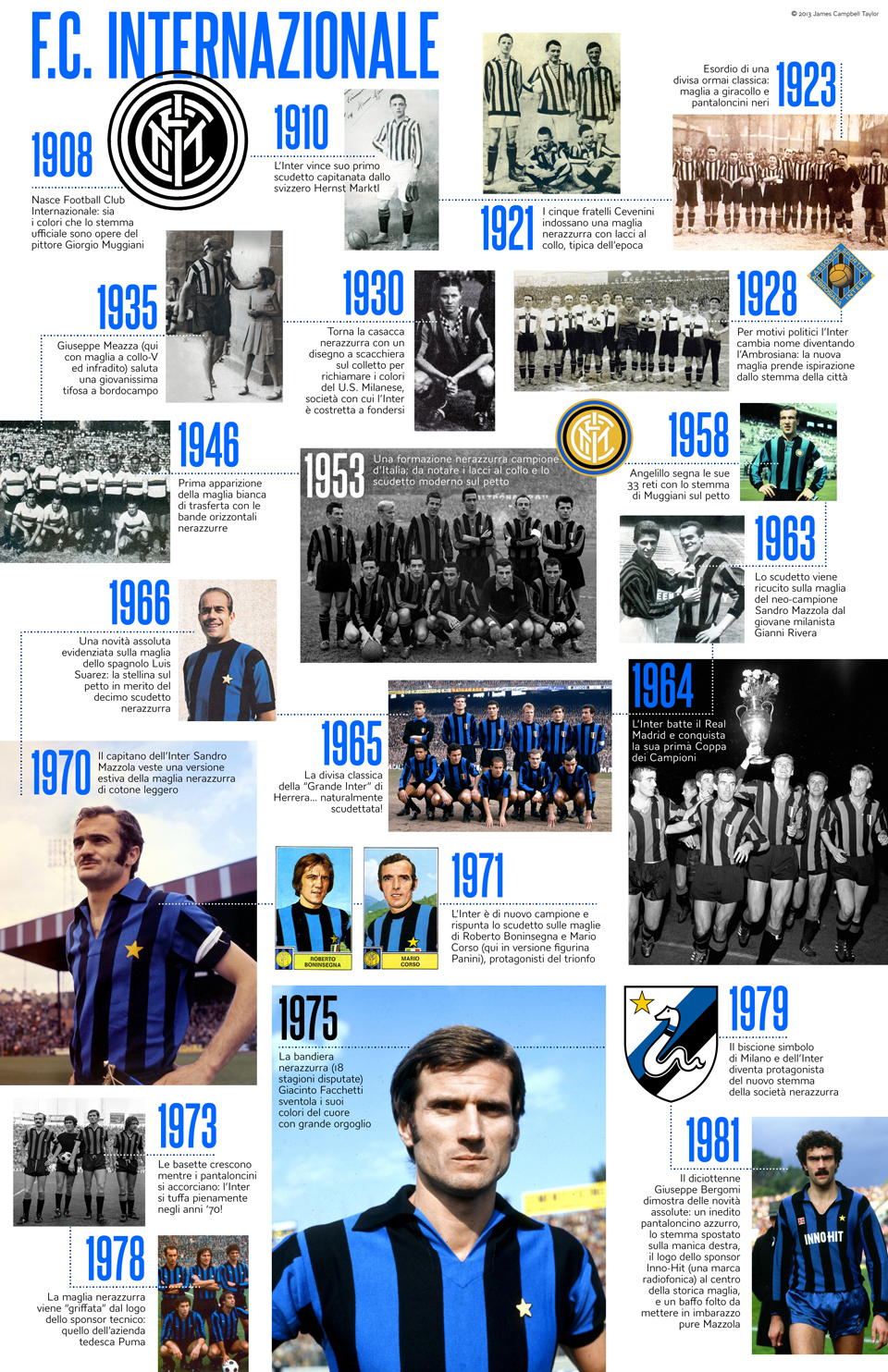

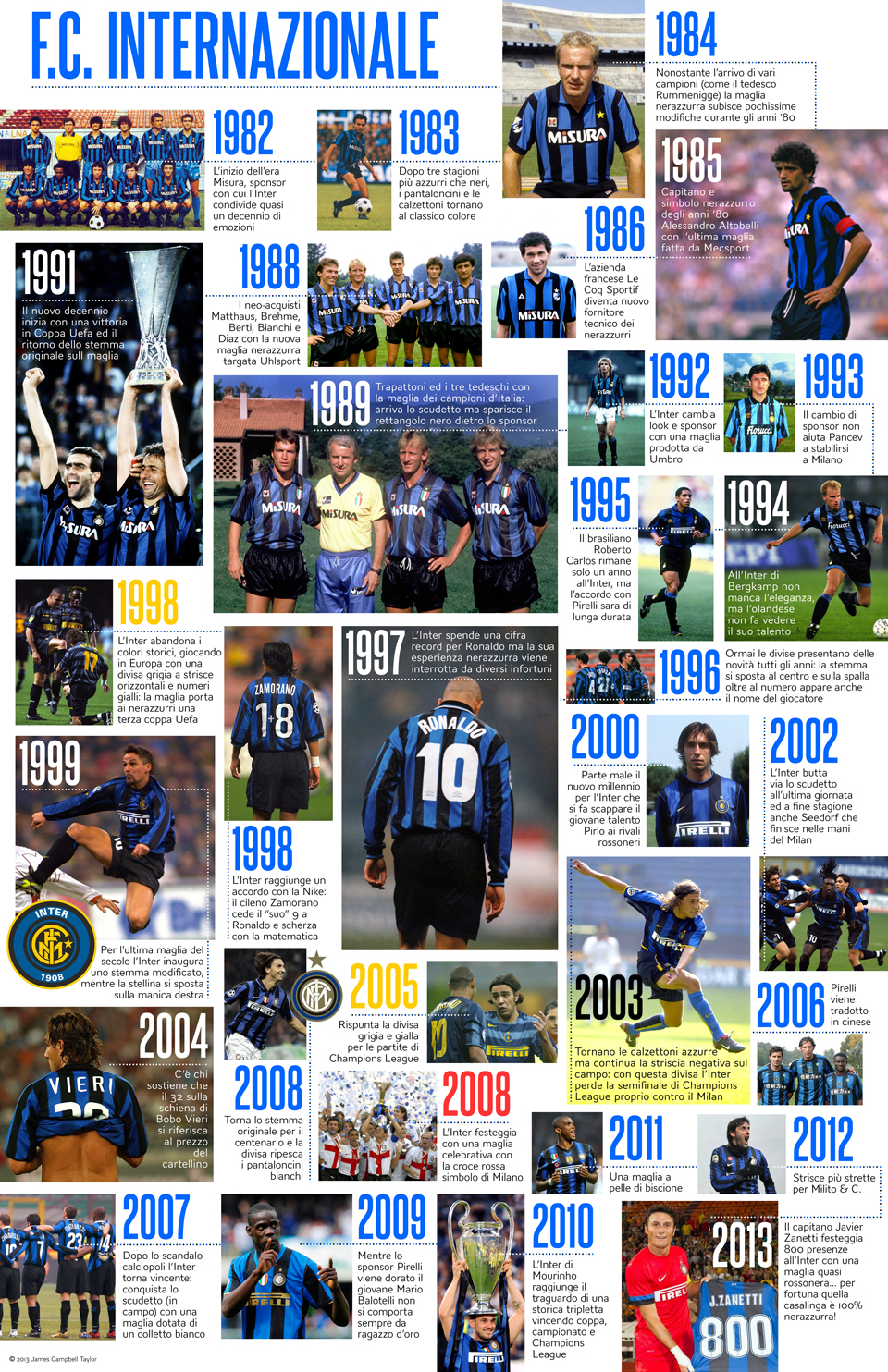

No doubt recognizing my credentials as a Serie A historian and football kit aficionado, the Italian literary magazine Inutile asked me to write an essay on a team’s shirt history. The magazine’s editor is an Inter fan so I put aside my purple allegiance to trace the 105-year journey of the nerazzurri. I also created a two-part, poster-size, timeline graphic charting the many sartorial highs (and occasional lows) of the famous Milanese club, finally putting to good use my encyclopedic vault of calcio-related archival material.

When Donald Fagen snarled disparagingly of “Show Biz Kids” in their “Steely Dan t-shirts” in 1973, he couldn’t have expected that forty years later he’d be embarking on epic cross-country tours, singing the same line night after night to thousands of fans dressed in over-priced garb emblazoned with the name of his very same band. The irony is not lost on Fagen nor his Steely Dan co-founder Walter Becker. Having given up touring in the mid-seventies, retreating to the studio to focus on the pursuit of jazz-rock perfection, the duo reformed a live band in the early nineties and have been on the road or in the studio ever since. They recently penned a song about their reincarnation called “The Steely Dan Show” (part celebration, part self-deprecation), suggesting the pair now warily embrace the commercial touring routine.

Tonight sees the band coming to the end of a 53-show U.S. tour, the cryptically-titled “Mood Swings 2013: Eight Miles to Pancake Day”. The final seven shows take place at New York’s Beacon Theatre, and as soon as I get off the 1 train at 72nd Street I am approached by several middle-aged men trying to sell me tickets and knock-off merchandise that goes for a third of the price of those inside the lobby. The bar offers a special $14 cocktail called “Deacon Blues”, which depressingly consists of Absolut vodka and Sprite. Why not a Zombie from a cocoa shell, I wonder. Or a Black Cow? Or even a Cuban Breeze, Gretchen? Tonight the crowd is the usual mix of aging hipsters and major dudes, kids with cool parents and couples of all ages who know a tasty horn chart when they hear it. I have a pretty good seat at the front of the lower balcony, and have time to admire the extraordinarily ornate interior of the old theatre, as well as the extensive selection of guitars lined up on stage.

At 8:45pm the band, minus its two leaders, swishes into a jazzy introductory overture, towards the end of which the two founding members of Steely Dan make their entrance. In bright red Nikes, customary Wayfarers and a grey shirt that he looks like he’s been wearing since last night, Donald Fagen slouches onto the stage with the purposefulness of someone who’s just awoken from an extended nap. Meanwhile, his partner in crime Walter Becker ambles into view from the left, his head bobbing from side to side as he noodles on a sparkling apple-green Stratocaster. Taking his place behind the keyboard, Fagen leads the band into an unlikely opener, “Your Gold Teeth”, probably the only pop song in history to make reference to Cathy Berbarian. Unfortunately it turns out to be the most interesting song choice of the evening, as the show which had been billed as “Request Night” quickly shifts into a run-through of the band’s most popular, radio-friendly hits (maybe that’s what the audience requested).

Fagen seemed in high spirits from the start. “Sit back, relax and let the good times roll!” he implored in a possible reference to his idol Ray Charles, whose performance traits behind the keyboard he has frequently appropriated. For a 65-year-old he sang really well, taking intermittent sips from an ever-present can of Coke and even wandering out from behind the keyboard a few times to play his melodica with gusto. I’d read reports of last week’s shows describing Becker’s stage presence as “confused”. Apparently one night last week he disappeared halfway through the show and never came back. Tonight he interrupted “Hey Nineteen” to perform his weird welcoming monologue (which I’ve seen him do twice before), only this time he rambled on for what felt like several minutes, and when the song finally picked up again I’d almost forgotten which one it was. Later he performed lead vocal duties on “Daddy Don’t Live In That New York City No More”. Becker’s evidently more suited to those slightly scathing, humourous songs (I’ve seen him sing “Haitian Divorce” and “Gaucho” before), whereas Fagen seems more at ease with the warmer, more human numbers, something that’s definitely reflected in their solo work.

Becker also had trouble settling on his instrument, frequently switching between at least six different guitars. In addition to the aforementioned sparkly apple-green Strat he also used a cherry-red Stratocaster, a cream Telecaster, a gold Gibson Les Paul, a Gibson Flying V and a Gibson Explorer. Jon Herington on the other hand was happy to rely only on a Gibson SG, Gibson Archtop and a Telecaster, coming up with a handful of devastating solos along the way. With his glasses and crisp blazer I always think he looks more like an interior designer or marketing director than lead guitarist, and I get the impression he’s reluctant to bask in the spotlight, preferring to hover near the curtain rather than soak up the audience’s roars of approval.

Clearly there is no discussion about stage presence or costumes, as everyone (with the exception of the girl singers in their little black dresses) seems to have shown up in whatever they happened to be wearing that day. Trumpet player Michael Leonhart sports a jaunty red fedora while his trombonist neighbor Jim Pugh looks like somebody’s dad in loose-fit jeans and running shoes. Although the juxtaposition is funny it only reinforces the sense that the show is more about expert musicianship than any kind of spectacle. When you read the bios of the individual band members on the official website you realize that these are among the very best musicians you’ll ever see, having between them played with everyone. The other stand-out performer is drummer Keith Carlock, who has probably one of the most challenging yet rewarding jobs in music. The rest of the band is referred to these days as the “Bipolar Allstars”, while the backing singers are known as the “Borderline Brats”. The all-female vocalists shared the lead on “Dirty Work” and a Joe Tex cover called “I Want To (Do Everything For You)”, the arrangement of which sounded exactly like “Chain Lightning”. During this song Becker introduced the band, describing Fagen in typically humourous terms: “…World traveller, organic gourmet chef and stern critic of the contemporary scene…”

They pile on the fan favorites towards the end, and the crowd seems very satisfied. Despite the hit-laden set list there is no room tonight for perennial live cuts such as “Bad Sneakers”, “Green Earrings” or “Josie”. Afterwards Fagen hands a pineapple that had been sitting mysteriously on top of an amp to a fan in the front row. The band returns for an encore and plays “Kid Charlemagne” (“Yes there’s gas in the car!”), allowing Herington to produce perhaps his best solo of the night. Becker and Fagen give a wave to the crowd and disappear again, leaving the band to play the audience out. It’s a slightly anti-climactic end to the show, and there is little sense of the musicians wanting to play any longer than the time allotted or give you a dollar more than your money’s worth.

This is the fourth time I’ve seen Steely Dan since they started touring again after an almost twenty-year hiatus: on the Art Crimes ’96 tour in Birmingham, at the Sanbitter Festival in Lucca in 2007, and once before at the Beacon in 2008. Over the past few years their week-long residence at the storied venue has become something of an Upper West Side tradition, and there is certainly a pervading sense of over-familiarity throughout the evening. Of course, there is no such thing as a bad Steely Dan concert, but this one was perhaps more for the casual fan of FM radio than for those of us who still have every note they’ve ever recorded on heavy rotation. The band is cooking throughout and as tight as ever, but I’d have appreciated a few less oft-performed album tracks to have been thrown into the mix, something that in the past I think they’ve always managed to do quite well. Rumours abound that Don ‘n’ Walt are working up a new record, so why not use the occasion to debut some new material, or at the very least throw in something off either of their most recent solo albums? Knowing Fagen’s encyclopedic knowledge of jazz and r’n’b I’m surprised he doesn’t branch out a bit and take advantage of that vast level of musicology to work some twists into the performances. They seemed to do that a lot when they first started touring again (see the live horn-driven version of “Reelin’ In The Years” on Alive in America), but tonight most songs were replicated exactly as they sound on the recorded versions. I kept listening out for how they’d come up with an ending for songs that fade out on record, which along with Herington’s solos and the backing vocals was the only element exclusive to the live performance.

A recent gimmick among aging rock acts has been the live reproduction of LPs in their entirety, something Steely Dan are not immune to, having performed shows this week devoted to the classic albums, The Royal Scam, Aja and Gaucho. Each of these shows began with backing vocalist Carolyn Leonhart dropping the needle on a spinning turntable on stage, a knowing joke that blurs the lines between live performance and recording. Tonight the newest song on the set list was originally recorded thirty-three years ago, but I think there’s a big difference between listening to old music at home and seeing/hearing it reproduced in person. A record is exactly that, and will always sound exactly the same. A concert is a totally different means of presenting the music, open to variation and spontaneity, with the exchange between performer and audience being more direct and reciprocal. I’ve always believed that a live act with any kind of longevity has to learn to keep things fresh, stay two steps ahead of their audience, even if it forces concert-goers to face the unexpected and even forgo hearing their favourite song. Otherwise it’s merely an exercise in nostalgia. Becker and Fagen surely know by now that those days are gone forever (over a long time ago… oh yeah).

Steely Dan, Beacon Theatre, October 5th, 2013:

Blueport (Gerry Mulligan cover — band only)

Your Gold Teeth

Aja

Hey Nineteen (WB extended monologue)

Show Biz Kids

Black Cow

Black Friday

Time Out Of Mind

Rikki Don’t Lose That Number

Daddy Don’t Live In That New York City No More (WB lead vocal)

Bodhisattva

Dirty Work (backing singers lead vocals)

FM

Babylon Sisters

I Want To (Do Everything For You) (Joe Tex cover, backing singers lead vocals, band intros by WB)

Deacon Blues

Peg

My Old School

Reelin’ In The Years

Encore:

Kid Charlemagne

Outro (band only)

A couple of years ago I wrote about what I had perceived as a growing trend in Hollywood for inserting the name of a movie’s main character into its title. While this tendency has not subsided completely, lately I’ve begun to notice other naming devices used by film and television producers (especially within the comedy genre) that do little to dispel perceptions that the industry’s creative well hath run dry. I no longer consider myself an avid viewer of network television, nor a frequent movie-goer (which I’d like to think says more about the deteriorating quality of both media than about me). But I live in New York City and have eyes, so I am well aware of what’s playing on screens both large and small, even if I would be reluctant to sit through most of it.

Using the character’s name as (or as part of) the title is a more recent phenomenon in relation to movies, but its application to the sitcom has a much longer tradition. This usually follows one of a number of successful formulas.

1) Character’s first name: Arsenio, Bette, Blossom, Cybill, Ellen, Frasier, Freddie, Hank, Jenny, Jesse, Joey, Kirstie, Mary, Maude, Nancy, Reba, Rhoda, Roseanne, Whitney;

2) Character’s name + character’s name: Dharma & Greg, Kate & Allie, Kath & Kim, Laverne & Shirley, Melissa & Joey, Mike & Molly, Mork & Mindy, Ozzie & Harriet, Will & Grace, and in a slight variation, Joanie Loves Chachi;

3) Character’s name + some kind of description of their state or circumstance: Caroline in the City, Everybody Loves Raymond, Everybody Hates Chris, Grace Under Fire, Hangin’ with Mr. Cooper, Samantha Who?, Suddenly Susan, Veronica’s Closet;

4) Multiple character names presented as a list: Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice or Zoe, Duncan, Jack and Jane. Seinfeld and Becker are rarities in that they used the title character’s last name, a convention more often applied to police detective series (it’s worth noting that neither show could be called “cozy” while both employed a more sarcastic brand of humour.)

As you will have noted some of these character names are supplied by the star on whom they are often loosely based. Lucille Ball (I Love Lucy, The Lucy Show, Here’s Lucy, Life With Lucy) and Bill Cosby (The Bill Cosby Show, The New Bill Cosby Show, The Cosby Show, The Cosby Mysteries) were rarely involved in anything that didn’t have their own name attached. The convention of The [insert star actor’s name here] Show has been applied to almost every beloved entertainer in American TV history. This year Michael J. Fox adds his name to a list that includes Andy Griffin, Bernie Mac, Betty White, Drew Carey, Doris Day, Donna Reed, Geena Davis, George Wendt, Jimmy Stewart, Jamie Foxx, Joey Bishop, Larry Sanders, Michael Richards, Mary Tyler Moore, Mickey Rooney, Phil Silvers, Paul Reiser, Tony Danza, Tony Randall and Tom Ewell.

Many sitcoms continue to revolve around the family unit — or some unconventional twenty-first century version of it — and it’s remarkable how many have included the word “family” in the title (All in the Family, Family Ties, Family Matters, Happy Family). This fall two more domestic comedies, Welcome to the Family and Family Guide, have landed on our screens, perhaps seeking to cash in on the recent success of Modern Family. A less common alternative is the cozy pluralization of the fictional family’s last name a la The Jeffersons, though we currently have two new families feuding for ratings: The Goldbergs and The Millers (not to be confused with the contemporaneous movie release, We’re The Millers).

Given the recent disintegration of the classic American sitcom format, there is something particularly quaint about such tried and trusted naming conventions. Far less appealing is the latest tendency for many recent shows to be lumbered with non-titles, or rather barely descriptive labels. This is by no means a new development, but perhaps gained popularity following the huge success of a mid-90s ensemble sitcom that started life as “Insomnia Café”, later becoming “Friends Like Us” before being abbreviated simply to Friends. Lately it seems this approach has reached absurd extremes. This fall season kids across America can see Mom on CBS and Dads on Fox. Perhaps the worst examples are Men of a Certain Age, We Are Men and Guys with Kids, all short-lived shows about, well, you guessed it). I was recently surprised to see a trailer for an Italian movie called 4 padri single (“4 single dads”), proof that the trend is not exclusive to this country or even to the English language.

This meta approach to giving shows deliberately uncreative titles reaches its nadir with what I call the “list” approach. I don’t know if Three Men and a Baby was the earliest case, but several sitcoms followed whose titles essentially described the cast in the most basic of terms: My Two Dads, Two Guys And A Girl (originally called Two Guys, a Girl and a Pizza Place, and not to be confused with the Robert Downey Jr. movie Two Girls and a Guy), Two and a Half Men, 2 Broke Girls and Girls are the best examples.

I’m not sure if cinema trends influence television or vice-versa, but there have been several movies (all comedies) in the last couple of years that do nothing to eradicate this annoying habit: Grown-Ups, Bridesmaids, Spring Breakers, Horrible Bosses, Identity Thief, Tower Heist, Zookeeper, Bad Teacher, even Bad Grandpa. In an age in which television seems to exist primarily for the purpose of generating social media posts it’s not surprising that priorities have shifted. Few people actually sit down to watch TV as it airs; instead the best parts of shows are enjoyed after the fact on YouTube or as live trending tweets. Similarly most movies are available on DVD or streaming before their cinema run has ended. Faced with such an excess of competition, the titles of TV shows and movies no longer have to appeal or intrigue, but rather explain a premise as quickly as possible, that would-be viewers can understand without even watching it. I can only assume that this irritating fad will subside only after reaching its obvious conclusion, in which titles are combined with a one-word review. Although incredibly, neither “Unfunny Sitcom” nor “Bad Movie” sound particularly far-fetched.

This is the Mary Help of Christians on East 12th Street between First Avenue and Avenue A. It was built on the site of the old St. Patrick’s Cathedral, took six years to build and was completed in 1917. Modeled on the Basilica di Maria Ausiliatrice in Turin, the new church immediately became the spiritual home for a multitude of immigrant families in the then largely Italian community, and has grown as a place of social and cultural significance in the East Village for almost a century. In 1953 it was the venue for the wedding of FDR’s daughter, Sara Delano Roosevelt, and Anthony di Bonaventura, the son of a 17th Street Italian barber. The church is referenced in the poetry of Allen Ginsberg, who lived across the street at 437 East 12th Street for many years. The intersection of East 12th Street and Avenue A was renamed Father Mancini Corner in honor of Father Virginio Mancini, the church’s parish priest from 1949 to 1986. The church closed in 2007, but every evening for the past four years as I’ve walked past I have seen a small group of women huddled on its steps praying quietly in Spanish.

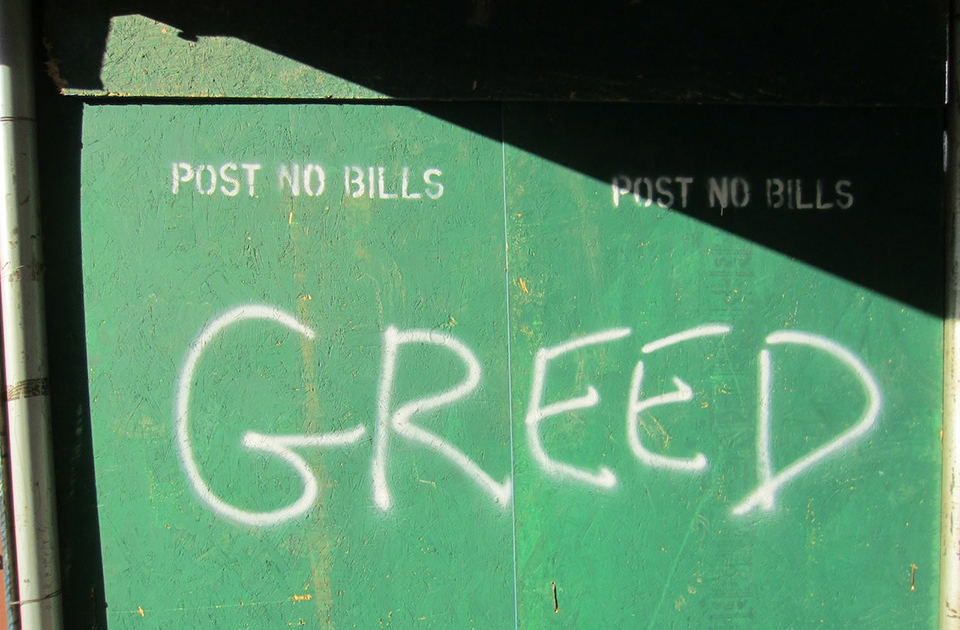

Earlier this year the church, rectory and neighboring school (essentially half a block) were purchased by developer Douglas Steiner, who soon revealed plans for “urban development.” “Urban retrogression” would be more accurate, because the specifics of the typically shortsighted project include the usual “prime retail opportunities” plus another non-descript, shoddily-built “luxury” glass condo, guaranteed to attract and house entire swarms of iPhone-gazing potential citibikers. Of course, it would have been far more lucrative in the long-term for Steiner to convert the historic structure for modern usage, but like most in his field he’s only after a fast buck.

Local residents and preservationist groups acted swiftly, appealing to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission that the historic structure be spared. The application was declined. This summer further protests against the demolition were held after fragments of a wall were unearthed which had originally formed part of the Catholic cemetery that predated the church. Among the 40,000-plus graves was that of Venetian librettist Lorenzo da Ponte, who worked with Mozart on Le Nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni and Cosi Fan Tutte. Again these pleas also were rejected.

By now this type of story is all too familiar to New Yorkers. Over the last few years I’ve watched as renowned and beloved aspects of the city’s vast heritage have been unceremoniously wiped out, eventually taking entire communities with them. Such destruction (both physical and spiritual) is now becoming more frequent and increasingly reckless. What this all amounts to is nothing less than a corporate whitewashing of the city’s history, culture and character—ironically the very same character that is used to lure certain types (and you know which types I mean) into neighborhoods like this one.

I may be naïve or romantic, or maybe just European, but that a place of such architectural, cultural and social importance can be destroyed against the valid wishes of a fearless and vocal community extending far beyond the borders of the East Village, all for the greed-driven or politically-driven benefit of a clueless few, leaves me incredulous. Yet it is highly indicative of the culture that has been perpetuated by this city’s highest powers in recent years. The consequence is that many New Yorkers – the real kind, those that think for themselves and see straight through the bullshit – find themselves victims of what can be best described as a culture war. As the minority it should come as no surprise to us that our side is losing.

“The poets ’round here don’t write nothing at all, they just stand back and let it all be.”

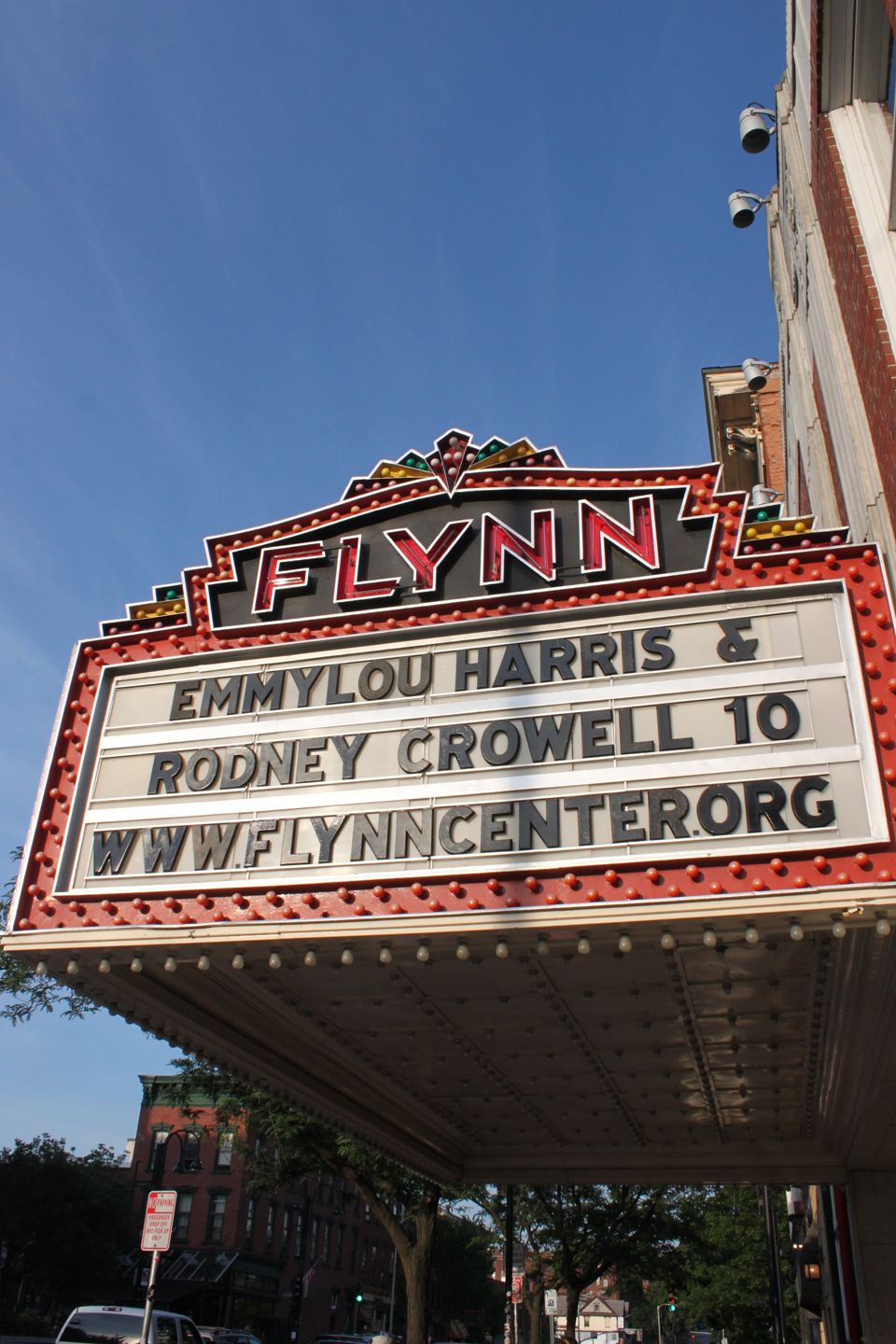

Ferrisburg, Middlebury and Burlington, VT, July 2013.

When I was a boy my best friend was another boy named Joe. We must have met when we were about four or five, and from that point on spent what seemed like most weekends together. Thanks to this near inseparable friendship, Joe’s parents quickly became close friends with mine. Both were artists — his father a sculptor and his mother a ceramicist — and both were pretty successful in their respective fields. My family and his would often go to the cinema or have dinner together at the weekends, and then one of us would sleep over at the other’s house (Joe and I had met before my brother Alex was born, but once he was old enough to walk the two of us became three). Joe and his parents lived in a large house on the corner of a main road. It had three floors and a separate building that acted as his mum’s workshop, as well as a spacious garden, where Joe and I spent whole days doing what probably amounted to nothing much. In the far corner of the garden underneath a giant pear tree was a two story construction made of scaffolding and planks of wood, from the top of which we could see over the fence and into the street. One day we rested a piece of drain pipe across the scaffolding and the fence and poured water onto unsuspecting passers-by. When one particularly irked middle-aged gentleman asked us what we thought we were doing Joe told him we were watering the pavement. On another occasion we spent an afternoon tossing over-ripened pears into the street, which was fun until the police knocked on the door.

Perhaps in an effort to avoid further run-ins with the law, Joe’s dad used the same scaffolding and wood planks to construct a life-size biplane on the lawn. From his workshop down in the basement he’d fashion toy swords for us out of wood. On another occasion he crafted us a pair of walkie-talkies, equipped with a plastic wire aerial and a knob that turned. It’s hard to imagine what kind of fun could be derived from what were essentially two wooden blocks painted black, but somehow Joe and I managed to keep ourselves suitably entertained for hours on end. Joe’s dad had travelled across the western United States, bringing home with him a number of interesting Native American artifacts that adorned Joe’s bedroom. He even had a wigwam out on the lawn that we never dared sleep in overnight. I don’t know how many days and nights I spent in that house but I can still recall every last detail, right down to the pale green sponge-like texture of the upholstery on the sofa and the paisley pattern engraved into the handles of the family’s cutlery.

When I was about ten, Joe’s parents sold their house and moved to another town, some forty minutes away. The new house was much smaller, but with the money they made on the sale they were able to buy a rustic property in the northernmost corner of Tuscany. Joe’s dad wanted to have access to the stone from nearby Carrara, a town known throughout the world for its marble. I remember them going there that summer to work on the house (which from the photographs I’d seen needed some attention). We’d already begun spending long vacations in Italy, and the following year we jumped at the chance to spend a week or two with them, and did so every summer for the next five years.

While the house itself was located in an area of Tuscany called il Lunigiana, in the province of Massa, it was only a short distance across the Ligurian border to La Spezia. Consequently the local license plates seemed to be evenly split between MS and SP. Exiting the A15 Autostrada at Aulla, it was a short drive to a small town called Serricciolo. From there we drove up a winding hillside road to the tiny hamlet of Verpiana, where we turned left around a large brick barn and into the dusty courtyard. The area was dotted with semi-abandoned pieces of farming equipment, hens clucked across the hay and cobblestones and a cat slept underneath the wheels of an already-vintage Fiat. The house was on the first floor: beneath it were three ancient arches under which Joe’s parents’ Citroën was parked. To get up there you had to walk up a semi-covered stone staircase with a wobbly metal handrail, which brought you out onto a spacious terrace. The house itself was extremely roomy with several bedrooms, some of which you could only get to via the terrace. The other details were as one would expect: terracotta floors, whitewashed walls, painted wooden shutters and iffy wiring.

Beneath the house was a maze of cellars and rooms that had clearly not been inhabited in decades, if not centuries. I remember one day Joe and I entered a secret door behind the archways where we’d parked the cars. If we’d explored further we’d have probably walked in on someone having lunch, as it seemed every home in the village was connected, as if buildings had sprung organically from that central point. A long white tunnel — more in the style of the Amalfi coast or a Greek island — extended out of the courtyard and lead to another road. Inside there were several other homes. Occasionally we’d run into other kids, who our attempts to befriend weren’t met with much success. They were quite unlike the other young Italians I’d met. At the other end of the tunnel was an alimentari, a small convenience store, the kind of place you enter through a beaded curtain and where the owner is a woman in slippers. It was a handy enough place to pick up milk or a box of pasta, but for a real supermarket we had to drive down to the next town, Serricciolo.

* * *

Serricciolo also had a bar next to the railway tracks, where we’d often stop for a morning coffee or post-beach refreshment. Joe and I often spent our time playing a football video game that ran on 20 lire coins. In addition to the aforementioned Sidis supermarket, Serricciolo also boasted a florist, a newspaper kiosk, a wedding dress shop, and a hardware store that also sold nice things for the home. Yet Serricciolo’s most important contribution to its range of local amenities was its pizzeria. The place was everything you want in a pizzeria and nothing more: plastic tablecloths, no atmosphere to speak of, and a pyramid of chocolate-covered profiteroles rotating behind the door of a glass fridge. The pizza was so thin it was almost transparent and its circumference so huge that I don’t know why they even bothered putting it on a plate. Always a purist when it comes to pizza I never veered from the margherita. The mozzarella would rapidly melt into the tomato creating a delicious sauce the colour of sunburn. I’d devour the whole thing in about ten minutes.

Sometimes after dinner we’d drive past the pizzeria to Fivizzano. This pretty hilltop town was also damaged during the war and is prone to earthquakes, but its main square, Piazza Medicea, has remained intact. There we’d order un gelato from the bar and eat it by the fountain (commissioned by Cosimo III de’ Medici), distinctive for its numerous carved fish from whose mouths spring jets of water. I loved the energy of those summer nights and the fact that families would be out together after midnight, kids running around in the dark, illuminated only by buzzing fluorescent lampposts.

On the way to Fivizzano was there was a nearby swimming pool, with a great water chute and high diving boards. It was kept in the shade by a forest of pine trees, and I remember one day a bee managed to sing me underneath my watch. Alex’s thick mop of blond hair (a “thatch” as my mum used to call it) meant he always drew attention from Italians. This was especially true at the swimming pool, where he’d quickly impress local teenagers by showing no hesitation in leaping into the water from the highest diving board.

After Serricciolo was Aulla, a mid-sized market town whose old centre was destroyed by Anglo-American bombings in 1943. The modern town that had sprung up in its place was a lot of concrete and marble, and decidedly unpretty. Aulla hosted a bustling market which we’d go to browse and pick up cheap frying pans, flip-flops or unofficial football merchandise. Meanwhile there were the usual shops: Benetton, Stefanel, plus a somewhat no frills sports store, where I bought my Milan 1990-91 shirt. I also have a photograph of myself standing outside the shop next to a life-size cardboard cutout of Franco Baresi. One day we noticed giant posters of football players (Baggio, Gullit, etc.) on display in the supermarket. The cashier explained they could be ours if we saved the wrappers from 12-pack boxes of Kinder Brioche. So for several days, Joe, Alex and me ate more of these apricot jam-filled breakfast cakes than was possibly healthy, but it was enough to earn us a poster each. (Mine, of a 22-year-old Paolo Maldini, still hangs on the wall of my apartment.)

When we weren’t visiting other towns or picking up provisions, we’d invariably spend the day by the sea. A place I loved to visit was Portovenere, a busy fishing town built into the cliffs and best reached by boat from the elegant port of Lerici. There was no beach, just a long cluster of boulders, with steps down to the water. When a boat sped across the bay the water would bounce up against the rocks. Joe and I used to snorkel around the tied-up rowing boats, trying in vain to catch darting minnows with our hands. We also collected broken fragments of old ceramic pots, which we took home and used to make a mosaic on the floor of the house. In the late afternoon we’d walk up to the gothic church of San Pietro, which offered spectacular breezy views of the Mediterranean. My dad used to always point out the grotto named after Lord Byron and tell us the story of how the poet swam across the bay to see Shelley in Lerici, and that Shelley later died in a boating accident just off the same stretch of coast.

There were beaches at Sarzana and San Terenzo but they were a little cramped, and so usually we drove to Marinella. We’d park opposite an Agip station on a road lined with pine trees, and spend the rest of the day there, sometimes until dusk. Unlike Liguria’s rocky coastline, Marinella was a classic Italian beach, packed with multi-generation families gathered under umbrellas and ragazzi spending the afternoon sunbathing or playing volleyball. I’d often run and get ice cream or bomboloni con crema from a little hut. We’d usually pack our own sandwiches, after which I used to begin to doze off on my towel. Through my dreamy state I’d hear the voice of the man carrying a large icebox filled with coconut. “Cocco! Cocco bello!” it would sing, more loudly as it got closer, before drifting away again, getting lost amid the soothing murmur of unintelligible chatter and gently breaking waves.

* * *

Life at Verpiana revolved around the terrace. Joe’s parents had furnished it with several pot plants and safari chairs and fold-up wooden chairs. There was a large table — or rather, a table top and two trestles — to eat at. It was too hot to eat lunch outside but when the sun had shifted the terrace became a lovely place to sit before dinner. Across the courtyard and beyond a neighbour’s clothesline was visible a spectacular mountain range that would turn pink each evening as the sun departed. I often wanted to believe that the central peak was the mountain featured in the logo of Paramount Pictures. (Years later the mountain I was thinking of was pointed out to me in Piedmont.) In the evening we’d hang our beach towels over the wall to dry and play football with one of those mini plastic balls they sell on the beach (one of the goals was the spindly railing at the top of the stairs, which meant every time a shot went in that direction someone would have to chase down after the ball and retrieve it before it bounced into an old cellar or punctured beneath a rusty tractor). On rare afternoons when Verpiana suffered a brief yet biblical rainstorm I’d hole up indoors and spend an afternoon reading or drawing. There was no television and the only place to listen to music was in the car, so we’d instead engage in epic ping-pong or Subbuteo tournaments, for which I remember creating paper advertising hoardings out of Brooklyn chewing gum wrappers.

I always looked forward to the evenings. I still remember what a blissful feeling it was to be standing in the kitchen under the bright glow of a single light bulb, watching the pasta fall into a vast pot of boiling water. Fresh out of the shower, tanned from the beach, a clean t-shirt and starving from having not eaten since lunchtime, the anticipation of another fun dinner out on the terrace was blissful. Though there were a couple of outside lights, the table was decked with ceramic candle-holders crafted by Joe’s mum, between which Joe and I would try to build wax bridges as the candles burnt down through the course of the evening. In the total silence of midnight we’d be able to spot bats circling around the barn and constellations directly over our heads, which is when my dad would start saying slightly ominous things like, “They’d never find me here.”

One of the neighbours was an elderly war veteran named Guido. He always said hello and sometimes he’d bring us a bottle of his own wine that was probably best described as “rustic”. My dad spoke better Italian than any of us and sometimes chatted with the old man over a cigarette. When my dad told him the route we’d taken to get here Guido opened his eyes with a hint of recognition. “Ah yes, Germany,” he said, as if summoning some vague recollection. “They eat a lot of potatoes there, don’t they?”

I sometimes wondered what Guido and his wife — a typical rural home-keeper who never took off her apron — used to make of us. I’m sure they were utterly baffled why a bunch of foreigners would want to spend summer in a part of Italy that no Italian would ever have reason to visit. Even at a young age, there was something quite embarrassing about it all. In between my fun I felt uneasy being in Verpiana for two sunny weeks when everyone around us had to spend all year there, year after year, and probably hadn’t been anywhere else in a long time. This feeling was exacerbated by Joe’s parents’ other guests, whose visits sometimes overlapped with ours. As nice people as they obviously were, their presence made the house feel like a ready-made facility for middle-class Brits to live some idealized version of a rustic Tuscan lifestyle. Nowhere could have been further removed from Italy’s celebrated tourist destinations. Verpiana, Serricciolo and Aulla were unknown, unfashionable places where real people lived, but have as much to do with my love of Italy as Rome or Venice or Florence.

Our relationship with Joe and his family ended abruptly, the reasons for which I won’t go into here as many details are still unclear to me. I haven’t seen Joe since Christmas 1994, but I understand he’s now married with a young son. His dad died a few years ago, but his mum is still working and as far as I know still visits the house in Verpiana. About six years ago, when I was living in Italy, my girlfriend (now wife) began taking singing lessons from a retired opera singer in Carrara. One Saturday in early summer I went with her on the train from Florence. While she had her lesson I strolled around the town. I had been once before, and remembered how the marble had turned the river water white. It was a warm day, so after lunch we took the bus down to Marinella. We walked past the pine trees, took off our shoes and stepped onto the sand. Many years had past and we were at the opposite end of the beach, but the view of the hills looked the same from any distance. Staring down the coastline I could just make out the yellow sign of the Agip station several hundred metres away, peeking through the haze like a mirage. Then, through the hypnotic sound of the sea I heard his voice, faintly at first, but getting louder: “Cocco! Cocco bello!”. As soon as it had sung, the voice started to fade away once more. And then, it was gone.

A version of this article, translated into Italian by Elisa Sottana, is on the site of Rivista Inutile.

Montréal and Québec City, July 2013.