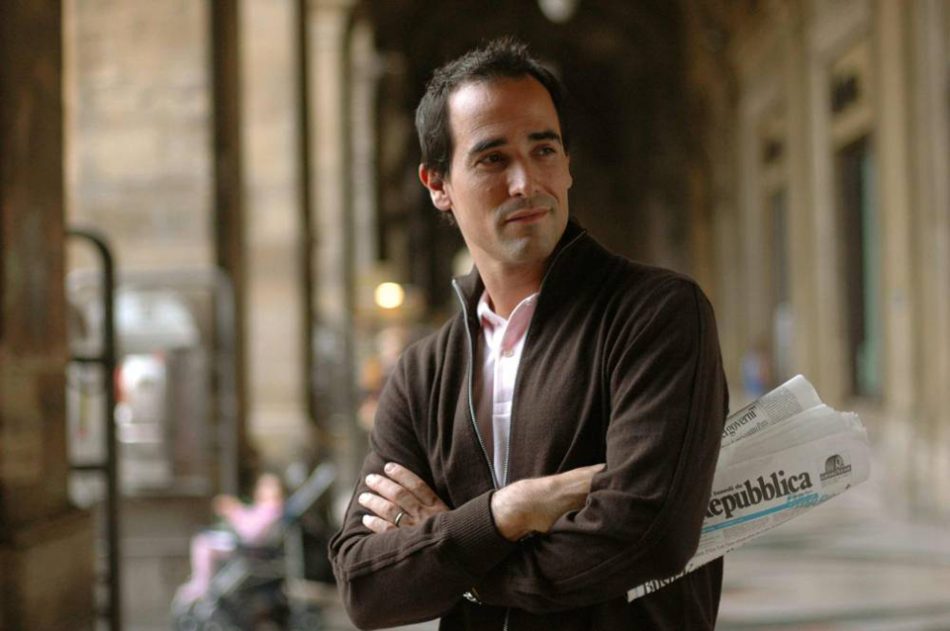

Napoli, October 2010.

Napoli, October 2010.

Florence, October 2010.

“One belongs to New York instantly, one belongs to it as much in five minutes as in five years.” — Thomas Wolfe

Last week, three years after moving to New York, and two and a half years after marrying my lovely American wife, I received my Green Card in the mail. According to the letter which came attached, I am now a Permanent Resident of the United States of America, although to me my new immigrant status still seems excessive. After all, I’ve only ever been to twelve of the fifty states, and generally never leave the island of Manhattan except to return to Europe. As John Lennon once said to an interviewer in reference to his deportation struggle, “Couldn’t they just ban me from Ohio?”

A colleague of mine left me a note which read “Congratulations, official New Yorker!” It was a sweet thought but one which left me confused. I wasn’t a New Yorker, just a Brit who got lucky enough to live here. Naturally, it begged the decidedly abstract question: when does a “New Yorker” become a New Yorker? I’ve heard it said that you’re only a New Yorker after you’ve lived here a certain number of years, but if so, how many? Whatever the answer may be I’m probably a few years away yet, but I’ve certainly feel like I’ve put in enough overtime studying this city to have shaved a few months off my sentence.

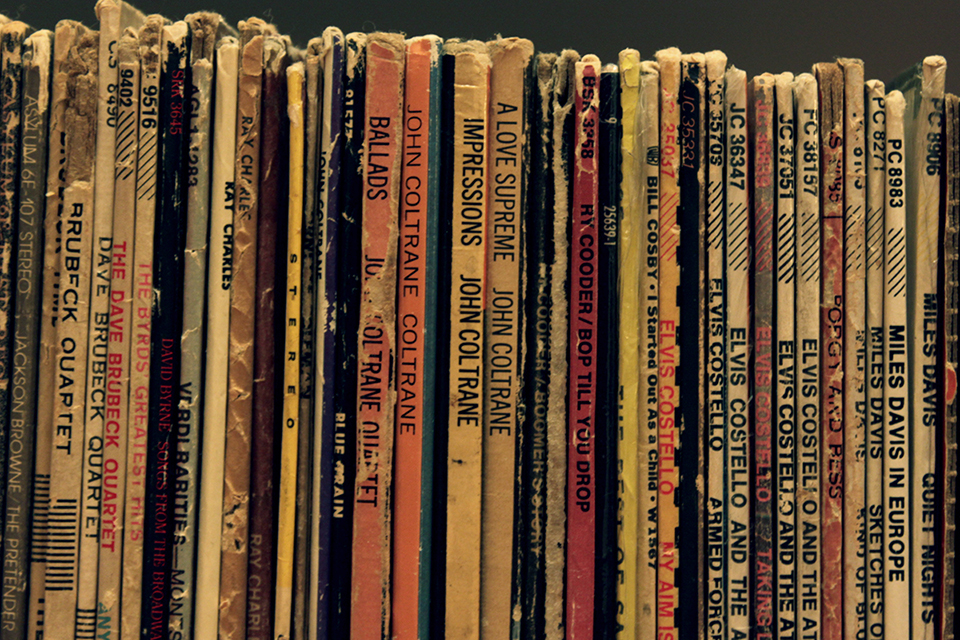

I know I have no greater right to be here than anyone else in my boat, but I doubt most new arrivals devote hours to meticulously researching the shooting locations of long-forgotten New York movies. Nor do they embark on a pilgrimage to the Upper West Side to photograph the city’s last remaining phone booths, or spend entire afternoons seeking out Manhattan’s humblest coffee shops on a self-assigned mission in search of the city’s finest egg cream. Nor do they drop $60 on an original 1974 Massimo Vignelli subway map (an exorbitant amount of money for something that was once handed out for free).

While I recognize that not everybody cares about these things (and nor should they), I also believe that a person is obligated to obtain an historical, cultural and social sense of their city, especially their chosen city, because I consider it important to understand where you are and what that means. When I see a group of young people in untucked shirts and trilbies exit a Barbie-pink stretch Hummer on Avenue B, it makes me sad that none of them look up from their iPhones long enough to realize they’re standing feet away from the former home of Charlie Parker. That is, if they know who Charlie Parker is to begin with. Personally I think they should make all would-be New Yorkers take a test. Anyone who fails has to spend six months in New Jersey swotting up on their Newyorkology. That would hopefully weed out all those who consider food trucks to be the height of urban chic.

Edward Hopper once said you get the greatest sense of a place upon arriving or leaving for the first time. I think he was right. To this day I still get a slight twinge the day before I leave New York or when heading to the airport at dawn, as if I begin to appreciate the greatness of the city knowing I’m going to be away from it (if only for a few days). But each time I return to Manhattan after a trip, I get a rush of the same excitement and awe that I felt the first time I got in the back of a yellow cab. Somehow the city looks, smells, even feels different. Streets I walk on every day are seen in a different light. Even the people with whom I jostle for space on the crowded sidewalk suddenly appear exotic and appealing. Could this be the same town I left less than a week earlier? That elusive magical feeling hits me like the first few seconds of “(Love Is Like A) Heatwave” and — at least for the duration of that cab ride — I remember why I always wanted to be here in the first place.

Maybe you become a New Yorker the first time New York feels like home. Not long after I moved to the U.S. I took a trip to visit my girlfriend’s family in West Virginia. It was the first time I’d left New York City, and I remember feeling an unexpected sense of blasé familiarity when I landed back at JFK, an airport I had until that moment associated only with extreme excitement and anticipation. Now, it was other places gave me that feeling; New York had become “normal”. The slightly bittersweet compromise but inevitable consequence of living somewhere you’d always dreamed of living is that that very special feeling — that urgent, frantic desire you once felt, perhaps even years before you got here — is lost. Of course, it’s replaced with something arguably much better: the real and more rewarding experiences that come with actually living somewhere.

Colson Whitehead says “You are a New Yorker when what was there before is more real and solid than what is here now.” I can definitely relate to that, and I’m always surprised just to what extent the New York in my head differs from the city I experience everyday in 2010. I confess to occasionally standing on street corners and squinting, trying desperately to recapture the sensation of walking down Broadway for the very first time, or even attempting to recall how I’d imagined New York all those years before I ever arrived. But whenever I start to wonder if this is a city best enjoyed through books and movies or my own imagination, something will jerk my senses suddenly and it all comes flooding back: early evening light on the side of a building, the sudden sight of one of the last Checker cabs bouncing down Seventh Avenue, or the inviting mix of pizza and Martha & The Vandellas floating out onto the sidewalk on a July afternoon. It’s all here, and it’s all real.

My daily commute is punctuated by the clatter of storefronts opening, a siren’s intermittent wail, hosed sidewalks, and, as I stand waiting for lights to change, the urban morning aromas of coffee, perfume and garbage. My heart lifts as I turn onto Irving Place and glimpse the Chrysler Building, half-hidden by summer’s haze or gleaming in the crisp winter sun. On the walk home I always remember to turn and look the wrong way up Lexington Avenue, to glance at all that steel and chrome rendered golden by dusk. Just in case I ever forget what I’m doing here.

In his 1949 essay “Here is New York”, E.B. White eloquently suggests there are three New Yorks, that of the native, the commuter, and the immigrant, claiming “the greatest is the last — the city of final destination, the city that is a goal.” He says the immigrants give the city “passion”, which accounts for its “high-strung disposition, its poetical deportment, its dedication to the arts, and its incomparable achievements.” Certainly New York, more than any other city in the world, owes its very existence — social, cultural, political, even physical — to the steady influx of people who have dared to dream that this could be their home.

Jeremiah Moss says “a New Yorker is someone who longs for New York.” While it’s true that not everybody who lives in New York automatically becomes a New Yorker, by the same token he implies you can be a New Yorker without actually living here. New Yorkers are a unique breed unto themselves, and maybe it’s enough to be one in thought and spirit. Maybe New York really is a state of mind. Maybe you’re a New Yorker when you can’t imagine living anywhere else. In which case, though my adjustment of status was only recently made official, maybe I’ve been a New Yorker all along.

All artwork by Elizabeth Lennard.

The other day I came across a tatty copy of New York magazine dated June 15, 1987. The cover story was entitled “The Buildings New Yorkers Love to Hate”, a list of the city’s most unpopular architectural landmarks which included the World Trade Center and the former PAN-AM Building. Most remarkable however, were the local listings towards the back of the magazine. The Restaurants section included just three eateries for the whole of Brooklyn. If you’ve been to Brooklyn lately this may seem hard to imagine, though if you were around in the late-eighties probably not quite so much. Indeed, the first time I visited New York eleven years ago it never even occurred to me that I might even venture across the East River.

When they hear the words “New York”, most outsiders think of Manhattan, and who can blame them? After all, when Frank Sinatra sang, “If I can make it there I’ll make it anywhere,” he wasn’t talking about Red Hook. Many visitors mistakenly consider Brooklyn another neighborhood, when it is actually New York’s most populous borough and existed as an independent city until 1898 (today it would still rank as America’s fourth largest). But no-one ever crossed the Atlantic with aspirations of making live hummus in Carroll Gardens.

But suddenly it seems Manhattan is no longer where it’s at. Indeed, if you believe everything you read, you’ll be told that Brooklyn is now everything Manhattan once was: cool, exciting, edgy. In short, the place to be. Before we go on I should make one thing clear: I’m not talking about the Brooklyn of Coney Island or the Dodgers or even Spike Lee; I’m talking about New Brooklyn. New Brooklyn looks a lot like old Brooklyn, except it’s a bit prettier and a lot more expensive. Though New Brooklyn garners plenty of media press attention, nobody does a greater job at promoting New Brooklyn than the New Brooklynites. The New Brooklynites are easy to spot. They are usually white, might have a beard, and definitely don’t speak with a Brooklyn accent. If you meet a New Brooklynite there’s a good chance they will soon tell you how glad they are to be living in Brooklyn, and how you really should be living there too.

Call me a contrarian, but when someone strongly urges me to do something, my natural inclination is to not do it, even if my original instinct might have told me otherwise. Maybe I’d have moved to Brooklyn by now if it weren’t for all those Brooklyn dwellers recommending I do so as soon as possible. Even my boss (who lives in Brooklyn) will regularly bring up the question as to why I’ve yet to move there, imploring me to “get off the grid”. I sometimes imagine he would enjoy enormous satisfaction were I to transfer out to Ditmas Park, so I too can endure an hour-long commute on the Q train at the cost of $89 a month. Many people who live in Brooklyn still work in the city; by living in Manhattan I currently use the subway only once a week at most, so I’m already saving money plus two hours out of every workday.

Much of the problem regarding the Manhattan-Brooklyn divide is definitely psychological, a syndrome by which I am affected as much as anyone else. I can be in Park Slope almost as quickly as it takes me to reach upper Broadway, yet I wouldn’t think twice about hopping on the 1 train up to Zabar’s for a cinnamon babka. Ask me to schlep out to Brooklyn and I’ll pull out a list of excuses.

Certainly Brooklyn’s rapid, ongoing transformation and continuing cultural divergence from Manhattan is arguably one of New York’s most significant changes of the last twenty years. There are several factors which New Brooklynites will always cite when discussing the advantages to their borough. The first usually concerns the lower overall cost of living. Yet while a railroad apartment in Bushwick may be considerably cheaper than a two-bedroom in the West Village, as New Brooklyn continues to generate hype so its rents in the more desirable (and exclusive) neighborhoods become comparable to those in Manhattan.

Such areas are also epicenters of Hipsterdom, an alarmingly unimaginative subculture whose primary concern is appropriating aspects of bygone eras and passing them off as its own. Skinny jeans, horn-rimmed glasses, plaid shirts and ironic facial hair: these are the cornerstones of the young New Brooklynite’s carefully cultivated wardrobe, items which must be worn at all times with the nonchalant attitude of someone who isn’t really trying. It also helps if you have some tattoos (you can almost guarantee that most of these people had very dull parents). Most hipsters look like they haven’t seen a gym — or the sun for that matter — since they left their altogether drearier hometowns (which to be fair probably wasn’t all that long ago).

Manifesting itself through music, fashion, even food, New Brooklyn has in recent years developed its own brand of taste and style that often appears a deliberate antithesis to Manhattan’s urban brashness and cutting-edge commercialism. Small businesses label their products as hand-crafted, home-made, organic or artisanal, in an attempt to differentiate themselves from the giant, soulless corporations which proliferate across the river. Yet the sheer number of like businesses which have cropped up over the last couple of years only diminishes their collective value. Suddenly it seems, every kid in Williamsburg is making Prohibition-style soda while attempting to grow a moustache. The appropriation of this down-home folksiness is clearly an attempt to lend weight to fleeting projects by referencing something real. In this sense Brooklyn is the crafts to Manhattan’s Arts. But as it continues to bemoan Manhattan’s so-called superficiality New Brooklyn has unwittingly created its own culture which is no less manufactured. At least Manhattan isn’t bullshitting anybody, and I’ll take an egg cream and a tuna melt any day over a gluten-free vegan cupcake.

I don’t wish to suggest for a minute that most of those who love Brooklyn aren’t genuinely happy living there, or that everyone should want to live in Manhattan or feel unhappy if they are not. Manhattan is definitely not for everyone, and of course, there is nothing inherently wrong with eating local or buying homemade, except for the holier-than-thou attitude that too often accompanies these ideas and lifestyle. Like the vegetarian who pulls a face when you order steak, the worst kind of New Brooklynite takes on an air of tremendous self-righteousness when you confess to enjoying the simplest of pleasures, as if drinking non-microbrewery beer could jeopardize your friendship. New Brooklynites’ constant praising of their borough can sometimes come off as obsessive, and in extreme cases it seems like an inverse reaction to not living in Manhattan, as if they are grappling with some trauma. Maybe they’re irked by Manhattan’s history of condescension towards the “outer boroughs”. Or maybe the very act of living in Prospect Heights gives them a warm fuzzy feeling of satisfaction akin to donating money to Africa or buying a T-shirt to benefit Haitian earthquake victims.

* * *

Of course, these phenomena are by no means exclusive to New Brooklyn’s population, but rather representative of the white, middle-class youth of America. Indeed, we are already witnessing the commodification of “New Brooklyn” as it enters the corporate mainstream. Take for instance the common brand of twee, faux-naïve songs which now permeate movie trailers and national television commercials for some of America’s biggest companies. In this week’s New York magazine (which incidentally lists nine restaurants in Williamsburg alone), Adam Sternbergh identifies every large city in the Western world as having its own Brooklyn, specifically a neighborhood with “nice blocks, good restaurants, and beards.” That the new Brooklyn can be defined so succinctly conveys everything about its limitations and its arch self-awareness. New Brooklyn, its look and sound, is now being used to sell everything from Japanese hybrids to portable e-book readers. Perhaps the most significant event in this trend was the launch of a “Brooklyn-themed” bar/restaurant set to open this autumn in — you guessed it — Manhattan.

That there are people who feel the need to define “New Brooklyn” — through its cuisine of all things, and on Manhattan turf — says a lot about the borough’s pervading complex of inferiority. It’s also in complete contrasts to the island’s greatest strength of total defiance and utter indifference. Manhattan cannot be tamed, and somehow manages to resist the waves of social or economic change. Sternbergh argues that it’s Brooklyn’s supposed positive qualities which make it so obnoxious, and that the same phenomenon could never happen with Manhattan because “they only ever made one Chrysler Building.” Manhattan could never become a brand because its brand is too vast, too diverse and far-reaching, Movies, art, jazz, tourism: these are things that are too beloved and universal to be considered “cool” anymore.

Though separated by a small body of water called the East River, Manhattan and Brooklyn can at times appear like two worlds in the same city, of which their inhabitants are two very different species. From its breathtaking verticality to its teeming street life, Manhattan, more so than any other major city, is a direct result of its geography. While Brooklyn and Queens are still home to some of New York’s largest ethnic communities, Manhattan’s cosmopolitan population is forced to exist on a narrow twelve-by-two-mile island. This tremendous concentration of people, their different cultures and languages, is what gives the city its unique, relentless energy, and in extreme cases can breed bouts of aggression or creativity, sometimes in the same breath. It’s these immovable confines which have helped make self-absorption and ambition two of the most common traits among Manhattanites — without space to move outwards, the city can only look inwards and upwards.

All of this has enabled Manhattan’s inhabitants to consistently defy categorization and stereotype as they go about their daily lives. They rarely question their presence on the island — many seem to live in a self-imposed exile of sorts, and are often unable to imagine themselves anywhere else. Though often perceived as neurotic or narcissistic, the truest Manhattanite is a model of fierce independence, flagrant individuality and unwavering positivity. To stroll the city streets is to experience a warm, unspoken understanding — a camaraderie among strangers, an unlikely mutual respect between all those who share a sidewalk.

Yet for many Manhattanites, moving to Brooklyn is seen almost as an urban rite of passage, an inevitable step in the life of a New Yorker as young adulthood gives way to parenthood, and that Chelsea studio suddenly becomes untenable. But for now, my favorite reason to visit Brooklyn is the ride home as the N train trundles over the Brooklyn Bridge. Downtown skyscrapers soar into view, my pulse quickens and I am thrilled at the thought of my apartment nestled hidden somewhere within all of that brick and concrete. Why would I want to be anywhere else? Perhaps Tom Waits put it best when he was asked to describe New York. “Well, it’s like a big ship,” he said. “And the water’s on fire.” I’m not quite ready to jump ship just yet.

Film stills from “Manhattan”, 1979 (United Artists).

The World Cup wouldn’t be the World Cup without its controversial episodes, and in the last week this tournament’s been full of them. Thanks to the blogtacular age we live in, such events can propel fans around the globe to express their unsolicited points of view with extra vociferousness. What’s most remarkable this year however, is that the incident that’s got people talking the most wasn’t all that controversial. But it was certainly dramatic. With the quarter-final between Ghana and Uruguay poised at 1-1 in extra-time, an entertaining and closely fought match was just seconds away from a penalty shoot-out when Uruguayan forward Luis Suarez cleared Dominic Adiyiah’s goal-bound header off the line with his fists, thus illegally preventing an almost certain winning goal. Portuguese referee Olegário Benquerença had no hesitation in showing Suarez a red card and awarding a penalty to Ghana, which Asamoah Gyan crashed against the crossbar with the last kick of the game. Uruguay won the subsequent penalty shoot-out 4-2, and advanced to the semi-finals for the first time since 1970.

Perhaps Suarez did little to ingratiate himself to Ghanaian fans when, moments after receiving his marching orders, he interrupted his journey back to the dressing room to celebrate Gyan’s penalty miss while halfway down the tunnel. After the game he perhaps overstepped the boundaries of good taste in comparing his crime to the most famous handball of all. “The Hand of God now belongs to me,” he joked, a banal reference to Diego Maradona’s fisted goal against England in 1986 which is likely to garner more headlines in England than in Ghana.

But while Suarez will, as expected, sit out Uruguay’s semi-final against the Dutch on Tuesday, there are those that feel that this particular sporting injustice warrants further investigation, starting with a lengthier suspension than just the compulsory one-match ban. Those outraged by the incident say Suarez — and by extension, Uruguay as a team — need to be suitably punished. What they fail to remember is that the appropriate punishment was dealt immediately, in the form of a red card for Suarez and a penalty for Ghana. After that it was up to the Ghanaian player to score; it’s not Uruguay’s fault that he didn’t. Any player who wouldn’t have done the same thing as Suarez surely shouldn’t be playing professional football, an attitude shared it seems by anyone who has ever been involved in the game, judging by the solidarity shown to the Uruguayan by television’s legion of football punditry.

In a World Cup which saw two staggering errors by officials the last round, this latest controversy — unlike those involving Frank Lampard and Carlos Tevez last weekend — at least cannot be pinned on the referee. The incident inevitably drew comparisons with Thierry Henry’s handball against the Republic of Ireland in a World Cup play-off back in December, in which the French forward controlled the ball with his arm before laying on a pass for William Gallas to score the winning goal. But Henry’s crime was far worse than Suarez’s, for two reasons. Firstly, the circumstances were not so extreme as to cause Henry to act instinctively: it was not the final minute of the match, and had Henry let the ball fall out of play he would have only conceded a goal-kick. Secondly, and far more importantly, is the fact that Henry’s foul was not spotted by the referee.

In basketball, towards the end of every close game (the final two minutes) the trailing team commits tactical fouls in the hope that the opposition will miss the free throw, allowing them to retain possession as quickly as possible. What we saw in Johannesburg was essentially the same tactic applied to football. It doesn’t happen as often in football simply because the consequences (penalty, red card) are far greater. Had Suarez committed the handball earlier in the match it would have been riskier for the team, but since it was in the dying moments he decided it was preferable to Uruguay’s elimination — a practical certainty had he let the ball fly past him and into the net. A friend of mine pointed out that this incident was unusual because Suarez had no incentive not to commit the foul (besides sacrificing his own personal involvement in a possible penalty shoot-out and the rest of the tournament) due to it occurring in the last minute of extra-time. But how does a referee determine at what point there would have been an incentive to concede the goal? Those who follow football are always complaining about a lack of consistency among officials; it would be highly hypocritical, as well as ludicrous, to expect a referee to apply different measures based on the match’s circumstances or how many minutes are left on the clock.

Many have gone so far as to brand Suarez a cheat. But breaking the rules and cheating are not the same thing. To cheat is to break the rules while seeking to avoid punishment. Of course, if a player breaks the rules he should be punished accordingly. But how have these critics managed to quantify the morality of a foul? By their rationale, should a defender not bring down a forward if he’s through on goal because it would be immoral? A foul is a foul: a trip in midfield is punished with a free-kick for the opposition; a handball on the goal-line is punished with red card and a penalty. What’s the difference?

Moreover, Suarez was not trying to cheat. He knew what he was doing and what punishment would be forthcoming (despite his “Who me?” gesture towards the referee as the red card was brandished). To describe Suarez’s actions as “immoral” is to suggest he shouldn’t have committed the foul in the first place. This, to me, is a moral misinterpretation of the game. When you begin to imply that certain fouls should not be committed in the name of sportsmanship, the whole sport unravels and is rendered pointless. Players have no moral obligation to FIFA, God, or anyone else – that’s why there is a referee. There is nothing whatsoever immoral about a handball: it was a foul, and on this occasion under extremely dramatic circumstances, but the referee saw it and made the correct decisions. Had he missed the incident, then there would have been suitable cause for outrage.

By extraordinary coincidence, Ghana were involved in an almost identical incident earlier in the tournament, when Australia’s Harry Kewell used his arm to stop a shot on the goal-line for which he too was rightly sent off. Had Gyan tucked his penalty away against Uruguay as he had against the Socceroos, I doubt many people would have spent the weekend criticising the South Americans. It’s also important to consider how reaction to this incident might have differed had the situation been reversed. I think much of the outrage stems from tired Anglo-centric footballing stereotypes: the “happy-go-lucky” Africans thwarted by the “cynical, cheating” South Americans. This reveals a tiresome double-standard among football followers, and shows exactly to what extent most people who saw an injustice in Friday night’s game allowed their opinions to be swayed by context. Several neutral fans I’ve spoken to about the handball incident strongly disagree with my take on it and have all put forward arguments as to why. But they are ultimately united in their inability to assert real culpability, each independently and vaguely describing Suarez’s actions as “not right.” So if you can’t blame the player, and you can’t blame the referee, perhaps on this occasion there is no-one to blame.

Remember the name: Kamil Kopúnek. For Italian fans the Slovakian can now take his place alongside Pak Doo-Ik and Ahn Jung-Hwan on the Azzurri’s podium of World Cup infamy. It may seem an unlikely trio, but all three players have in their time put paid to the Italy’s World Cup hopes, and in doing so represent the lowest points in the four-time winners’ otherwise impressive tournament record. But while defeats to North Korea in 1966 and South Korea in 2002 sent shockwaves reverberating around the football world, Italy’s lacklustre performance and ultimate capitulation in 2010 had a certain inevitability. After disappointing 1-1 draws against Paraguay and New Zealand, a win – while not essential – was certainly the Italian objective in their final group match against Slovakia. Instead, the Azzurri found themselves two goals down after 73 minutes, and despite rallying a late fight-back, Italy’s elimination was effectively sealed the moment late substitute Kopúnek burst between two defenders to lift the ball over Fabrizio Marchetti with his very first touch of the game. So low were expectations surrounding the defending champions’ campaign in South Africa that reaction to Slovakia’s third goal was less one of outrage and more a collective groan of relief and resignation.

Italy’s disastrous exit from the World Cup in 2010 made the euphoria of Italy’s victory in Berlin – still fresh in the memories of all Italians – suddenly seem every bit four years ago. In 2006, few would have predicted both finalists in Germany crashing out at the first hurdle in South Africa. And yet while the French can point to internal struggles and their federation’s misguided faith in an increasingly eccentric coach, whose bizarre alienation of fans, press, staff and players is reason enough for their shambolic demise, the Italians have fewer excuses. Certainly that was the view of fans, who on Italy’s return from South Africa, subjected their fallen heroes to a tirade of jeers and abuse as they trudged with hung heads through the arrivals gate at Rome’s Fiumicino airport.

To assess just how Italy went from World Champions to national disgrace requires a quick rewind to Berlin four years ago, when, just as in 1982, Italy’s national team emerged from the wreckage of domestic scandal as unlikely but worthy World Cup winners. The Italian coach Marcello Lippi had already decided not to renew his expiring contract with the FIGC (Federazione Italiana Giuoco Calcio), and three days after enjoying what he described as his “most satisfying moment as a coach”, was replaced by former Italian international Roberto Donadoni. It was a surprising choice: Donadoni’s greatest achievement as a coach so far had been to lead unfashionable Livorno to the top half of Serie A, and he certainly lacked experience at a major club. He was also faced the unenviable task of taking over a winning team in which any negative result is bound to be greeted with criticism. With the team still riding the highs of Berlin, Donadoni’s side’s performances were always going to compare unfavourably with Lippi’s, and the new coach struggled to assert his own identity on the world champions. It was a reign which seemed doomed from the start: Donadoni’s contract contained a clause stating it would only be renewed should Italy reach the semi-finals of Euro 2008 — when Italy were eliminated in a penalty shoot-out by Spain in the quarter-finals, everyone knew the game was up.

More surprising was what was to follow. The FIGC, in an unexpected move, recalled Lippi, who had spent the two years since the World Cup on the beach and at home in the Tuscan coastal town of Viareggio, basking in his new life as a national hero. Arriving at his first press conference since being recalled out of retirement, Lippi appeared tanned and relaxed, happy to once again don the federation blazer and “ready to pick up where [he] left off.” This statement of intent sent a twinge of discomfort down the spines of watching fans. The phrase “minestra riscaldata”, literally “reheated soup” is used in Italian soccer circles to describe the ill-conceived return of an ex-player or coach to his place of former glory, the idea being that it’s never as good second time around. Keen observers had to ask why Lippi, having achieved the sport’s ultimate accolade, would choose to give up a life of permanent hero-status to take Italy to another World Cup? The Azzurri’s victory in 2006 may have seemed unlikely at the outset, but even less probable was a repeat in 2010. Only Vittorio Pozzo, Italy’s coach in 1934 and 1938, had led a team to back-to-back successes, and not since Brazil in 1958 and 1962 had a nation won two World Cups on the bounce. Yet Lippi seemed happy to risk forever tarnishing his image of cigar-chomping hero of Berlin by attempting this extraordinary double.

Italy’s World Cup-winning captain, Fabio Cannavaro, was guilty of a similar arrogance. Unlike former captain Paolo Maldini, (who retired from international football after the 2002 World Cup, only to watch his would-be teammates lift the trophy four years later), Cannavaro had won it all but still wanted more, just like Lippi. Majestic at the World Cup four years ago, his performances in Germany were enough to earn him the Ballon d’Or in 2006. A World Cup victory seemed like a natural moment to call it a day, yet Cannavaro continued to lead the Azzurri, despite showing inconsistent form since returning to Juventus from Real Madrid. Once one of Italy’s quickest defenders, Cannavaro’s rapid decline culminated, sadly, in being made to look every bit the 36-year-old in South Africa.

* * *

The defending champions qualified for South Africa relatively comfortably, yet Lippi’s dependence on the core group of players that had triumphed in 2006 spoke volumes about not just his short-term priorities but also his obsession with Italy’s World Cup win four years earlier. Many questioned the reliance on certain players from Juventus: given the Turin club’s poor season the inclusion of wayward stars Camoranesi, Iaquinta and the aforementioned Cannavaro this time around seemed to have more to do with Lippi’s strong ties to his former employers. Lippi’s coaching philosophy emphasises team spirit and unity, but while the heroes of Berlin still had a role to play, many had lost the form they’d showed four years ago, and – perhaps more importantly – all were four years older. Lippi’s responded to critics by reminding them of his World Cup pedigree, and to those who raised concerns over the age of the squad pointed out that its average age was actually younger than in 2006. But in Germany Lippi had struck upon a group of top professionals players at their peak, in 2010 the gulf between levels of experience was startling.

Perhaps in an attempt to silence doubters Lippi selected several younger players who shared just a few caps between them as late inclusions into the squad. All had enjoyed positive domestic seasons yet none had been used regularly during Italy’s qualifying campaign and all lacked international experience (the fact that most were plucked from Serie A’s smaller clubs meant they were unfamiliar with the kind of pressure reserved for top-of-the-table clashes or matches in the Champions League). Though their selection seemed a knee-jerk reaction by Lippi, some of these players were immediately thrown into the deep-end in South Africa. Genoa left-back Domenico Criscito and Fiorentina’s elegant playmaker Riccardo Montolivo acquitted themselves well in tough circumstances, but others, such as Juventus midfielder Claudio Marchisio and Cagliari goalkeeper Fabrizio Marchetti, appeared out of their depth. Montolivo and Marchetti only became first choices due to injuries to otherwise certain starters: Milan’s regista Andrea Pirlo damaged a calf just days before the tournament, while Gigi Buffon bowed out at half-time in Italy’s opening match after aggravating a problem with his sciatic nerve, an injury which ruled him out of the rest of the competition.

Though injuries to key men naturally proved a massive blow for Italy, the team was further hampered by Lippi’s disparate squad, which consisted of too many players unused to performing at this level. For a country with a long history of world-class playmakers, Italy went into this World Cup without an out-and-out number ten, a designated trequartista or fantasista in the Roberto Baggio mould. Without a player with such qualities, in all three of their matches Italy looked desperately short of creativity in the final third. At 35, Alessandro Del Piero was judged past his prime, while Francesco Totti’s protracted retirement from international football had effectively excluded him from rejoining the squad. Lippi’s stubbornness is perhaps most evident in his failure to call temperamental forwards Antonio Cassano and Mario Balotelli to the international fold. While Balotelli still shows regular signs of immaturity, Cassano has consistently impressed for Sampdoria over the last two seasons, helping the Genoese club to qualify for the Champions League for the first time in eighteen years. Yet Lippi continued to ignore him to the frustration of fans, often refusing to answer the press’s questions regarding the player’s exclusion.

The attitude of Italians — coaches, players, press, fans — before a World Cup is typically one of cautious optimism (or false pessimism). You may say Italians love a crisis: it takes the pressure off and makes an ultimately positive campaign all the more enjoyable. The national team is a notoriously slow starter in major tournaments, and most fans expect a rocky road to success. Yet this year Italy started poorly and only got worse, and there was a pervading sense of imminent failure prior to the defeat against Slovakia.

South Africa 2010 officially ranks as Italy’s worst ever World Cup performance. Just as in 1966 and 1974, the Azzurri failed to progress from the group stage, but this year they were unable to record a single victory in three matches — against Paraguay, New Zealand or Slovakia — finishing bottom of Group F. Following the disastrous elimination, it was Lippi who predictably received most of the blame. The coach even shouldered all responsibility in his post-match press conference.

Certainly Italy’s notorious press was quick to pounce. Alberto Cerruti, chief football correspondent of the Milan-based daily La Gazzetta dello Sport, described Italy’s performance as “unwatchable”, but seemed particularly disappointed with the casual manner in which Italy’s hard-earned title was relinquished. The director of Rome’s Corriere dello Sport, Alessandro Vocalelli, was more scathing, appearing on an online video just hours after the final whistle to bemoan Lippi’s “incomprehensible selections and inexplicable tactics” which had resulted in a “total, humiliating failure, from which nobody should be exculpated.” Yet others saw a greater issue with Italian football at large. Former Milan and Italy coach Arrigo Sacchi, himself no stranger to the scorn of critics, felt the root of the problem lay in Italy’s culture of “ignorance and violence”, citing a “crisis in the Italian system.”

* * *

Sacchi may be going too far by condemning contemporary Italian society, yet the state of the country’s game has been in decline for several years, to the extent in which it has become almost de rigeur to disparage Serie A, Italy’s domestic championship, once the most admired league in Europe. Sacchi pointed to the fact that Italian clubs crashed out prematurely in European competition last season. The one exception, Inter, have a foreign coach and an almost completely foreign squad. Indeed, of the twenty-three players Lippi took to South Africa, not one hailed from José Mourinho’s treble winners, the first time ever an Italian World Cup squad has not contained a single player from the nerazzurri. The conclusion one takes from this is that there is an excess of foreign players in Italy, whose presence denies promising Italian youngsters the chance of breaking through at the biggest clubs. Consequently, Italy’s 2010 squad included players from Genoa, Bari, Udinese and Cagliari, clubs hardly renowned for providing members of the Italian national team.

There are those in Italy that have suggested the return of a restriction on the number of foreign players a team may field at one time. But Italy is definitely not the only nation with a strong domestic league faced with this dilemma. England has also discovered that top-class foreigners may make for an entertaining league but their presence can be detrimental to the national team’s success. Spain – despite the plethora of foreign players in La Liga – seem to have solved this problem by selecting a squad mostly comprised of players from the two biggest clubs, Barcelona and Real Madrid. In contrast, German clubs work in closer conjunction with its federation, and their philosophy of investing in youth rather than spending heavily naturally encourages a strong national side.

FIGC president Giancarlo Abete has already announced an inquiry into Italian football’s “structural crisis”, but to suggest a shake-up of Italian system is excessive. The problems cited as causes of Italy’s poor displays in 2010 were already in place in 2006, when Italian football was also still reeling from the aftershocks of calciopoli. Some claimed it was this scandal which galvanized the team to victory in Germany, and Italian players certainly appeared lacking in motivation in South Africa. But Lippi was correct to blame himself: his return was gearing solely towards this event, and so he had no interest in making long-term plans and no vision of the future since it did not concern him. He was obsessed with the victory of 2006, and intent on repeating it all costs, at the expense of his own better judgment. Sadly for Italy, he did not have the means — either tactically or technically — to realize that dream. The FIGC showed desperate short-sightedness in rehiring Lippi, who in turn showed an alarming degree of footballing-masochism in attempting a second win in succession. For all Donadoni’s inexperience, had the Italian federation stuck by him Italy would have probably arrived in South Africa with a more balanced and settled side. Likewise the younger players who did not appear ready at this tournament would have no doubt been groomed specifically in preparation for the World Cup stage.

The effects of calciopoli have tempered spending in Italy, and over the last two seasons the biggest Italian clubs –Inter, Milan, Juventus, Roma, Fiorentina and Sampdoria — have put their faith in local young players who have grown into first-team regulars. Lippi’s replacement, 52-year-old Cesare Prandelli, has been selected by the FIGC specifically for his proven track-record with younger players. At Verona, Parma and Fiorentina specifically, Prandelli had built attack-minded teams around the promise of youth. Though he spent six seasons as a player at Juventus, Prandelli may benefit from having never coached one of Italy’s biggest clubs, and his lack of close connections to Italian football’s superpowers may work in his favour. Certainly he will employ a fresher, more open approach to player selection, already stating that Cassano and Balotelli will figure in his plans. More unexpected were his comments surrounding the sometimes controversial oriundi (naturalised citizens eligible for the national team) whom he declared “new Italians.”

While Italians may be Italy’s biggest fans, they’re also its harshest critics, and once the dust settles on Lippi’s second era in charge they’ll probably realise the future doesn’t appear quite so bleak. It would take a brave man to bet against Italy going far in Brazil in 2014. As this World Cup has already proven, four years can be an awfully long time in football.

In case you hadn’t noticed, the World Cup got underway last weekend in South Africa. For one month every four years, the planet’s greatest sporting event has, historically, had a tendency to consume my every waking second. This year is no different, although since Italy lifted the trophy in 2006 I’ve obtained United States residency, meaning I am experiencing the tournament from this side of the Atlantic for the very first time. This situation has led to some interesting observations, some more expected than others, as I grapple with the clichéd notion of being an avid soccer nut in a country that — as we’re so often told — just doesn’t care.

Johannesburg is six hours ahead of New York, so I get to watch the day’s earliest match before leaving for work. Once in the office I close my internet browser and hunker down until I can return home, where, thanks to the miracle of DVR, two more games await my viewing pleasure. Though avoiding the score has proven more difficult than expected. I’ve had to change my route several times when I’ve seen soccer fans amassed outside a sports bar, and was even forced to move to the other end of a subway car when I heard some Brazilians talking futebol.

This isn’t the first time I’ve had to set the alarm for football matches. During the 2002 World Cup in Korea and Japan (when I was still living in England), most games were scheduled for the early morning, a novelty which resulted in BBC commentator John Motson developing a tiresome fixation with breakfast-related puns. Watching football on American networks can also bewilder, but for entirely different reasons. I still don’t understand why the commentary is called “the call” (as in “Martin Tyler with the call”) or why half-time is known simply as “the half” (“We’re goalless at the half.”). The alternative is the local Spanish language channel Univision, where the World Cup is co-hosted by young latinas in figure hugging national team jerseys, and any punditry is generally forsaken in favor of dancing, chanting and fervent flag-waving. Over on ESPN coverage is generally quite polished, with some big names on the panel: Klinsmann, Gullit, McManaman, McCoist, Lalas, Bartlett, Martinez (OK, some names are bigger than others). It’s clear the anchors are being fed information about players and previous tournaments by a soccer intern with encyclopedic knowledge of World Cup history, in a desperate but comprehensible attempt to dispel the myth that Americans know nothing about the game.

Whether you see it as a failure or a refusal, the fact that America has never fully embraced soccer is both fuel for those who dismiss the sport and a burden to its genuine fans. New York, of course, is a bit different. The city is still a natural port of call for anyone arriving from overseas or across the border, and some 36% of the current population is foreign-born. That’s a lot of soccer fans. New York State has no official language: English is obviously the de facto language but of the nine million people who live in the city less than half are native English speakers. On a day like today — when the air is thick and temperatures hit the mid-90s and football is blaring out of every bar, deli and taxicab – New York feels a lot closer to Naples or São Paulo than the United States.

That’s not to say the locals don’t make themselves heard. Yesterday I saw dozens of young Americans in USA jerseys heading to bars to watch their team’s match with Slovenia, while for several weeks shoppers on 57th Street have been subjected to Clint Dempsey’s screaming face looming large on the exterior of NikeTown. The United States’ games have even made the front pages of the Times, Post and Daily News. Despite only intermittent success in recent years, interest in the national team has steadily risen to a point where they today merit respect and generate media frenzy and support during the World Cup. Many casual American soccer fans become genuinely curious about the tournament, and perhaps even a tad envious of the kind of passion it invokes in people of other nationalities.

But come September it’s unlikely these same fans will be getting up at nine on a Sunday morning to watch European league matches. For this reason I sometimes sympathize with the professionals representing the United States, as they’ve had to work doubly hard to garner support from skeptics and casual, fair-weather fans whose interest is piqued only every four years. It’s like when people get excited about synchronized swimming during the Olympics.

A college friend of mine (and self-confessed soccer ignoramus) wrote to me recently asking me for my take on why the game has never taken off in the United States. After all, since the 1960s a host of characters from the worlds of football, politics, entertainment and business have tried to make soccer a more serious sport here, without ever fully succeeding. In the 1970s some of the sport’s biggest names — including Pele, Beckenbauer, Best and Cruyff — made the NASL a marketing man’s dream, but the novelty wore off by the early 1980s and the league collapsed soon after. In 1994 the United States even hosted a highly successful World Cup (breaking all attendance records), but the MLS (which was created as part of the U.S.’s hosting bid) has had a turbulent history ever since, and remains a relatively weak league whose rosters are populated mainly by young American talent and veterans from South America, despite more recent high-profile European arrivals, such as David Beckham and Thierry Henry.

Soccer is the most played sport at high-school level in this country, and extremely popular in the major cities and particularly among the under-30s, but I don’t think it will ever “take off” in the way my friend was implying. The problem is precisely that: football doesn’t really “take off” anywhere – it’s ingrained culturally and people either get it or they don’t. Sadly for America everyone gets it but them. In Asia, large populations with growing economies such as Japan, China and India, have embraced the game more fervently in recent years, but they didn’t have their own hugely popular and highly lucrative sports leagues in place. In the United States the NFL, MLB, NBA and NHL are very much ingrained; soccer is not really necessary, neither economically nor culturally.

Then of course there is the game itself. A lot has been made of the cautious nature of the first round of matches at this World Cup, but it seems the ones who complain about the football (or the vuvuzelas for that matter) are the ones who don’t really enjoy soccer and probably begrudge having to sit through it. Many Americans I’ve spoken to this week have questioned the number of matches which have ended in parity, their impression being that a tied result is somewhat unsatisfactory. That a game must have a winner strikes me as a deeply American idea. I got into a very heated row with my boss twice this week after he suggested football would be improved if they eliminated draws from the sport entirely. Most surprising when you consider my boss is Italian — albeit one who moved to the Bronx in 1970 and now catches a football match only every four years (and then only when the Azzurri are playing). Major League Soccer conducted a similar experiment when it relaunched back in the mid-nineties. Concerned with the prospect of tied games, the league’s commissioners imposed an instant one-on-one sudden death shoot-out in the event of a match ending level after ninety minutes. In a perverse twist on the penalty shoot-out, the forward would start with the ball from the halfway line with only the goalkeeper to beat. This attempt to avoid alienating mainstream sports fans by making league matches — and penalty kicks themselves — more exciting only alienated soccer purists, and the league soon reverted to a conventional win-lose-draw points system.

In this regard both the MLS and my boss were guilty of seeing the game purely from the perspective of entertainment, which in this case means the ball crossing the goal-line. Personally, I’d always prefer to watch a tight 1-1 draw between two quality teams than an end-to-end goal-fest between two average ones. Fans who describe close World Cup or Champions League matches as “boring” also fail to recognize one of the elements that makes the game so special. Football is different to practically all other sports in that scoring is supposed to be difficult, so when a goal is scored it’s a big deal. It is a game built on patience and tactics, which of course enhances the tension and drama, which in turn are what make important games so absorbing. In basketball there is no element of tension or drama until the last 120 seconds of the fourth quarter, and that’s only if the teams are closely separated.

The very nature of football is contrary to the instant gratification provided by high-scoring American sports, which are first and foremost entertainment (and big business). Football is obviously entertainment in Europe too (and an even bigger business globally), but there are deeper cultural, social and political elements that give the game a greater resonance beyond the stadium, which if you’ve never lived in Europe or South America is perhaps not something that’s easy to comprehend. It’s for these reasons more than any other that I think soccer remains a sport that most Americans won’t think of again for another four years. But until then, if they ever change their minds they know where to find the rest of us.

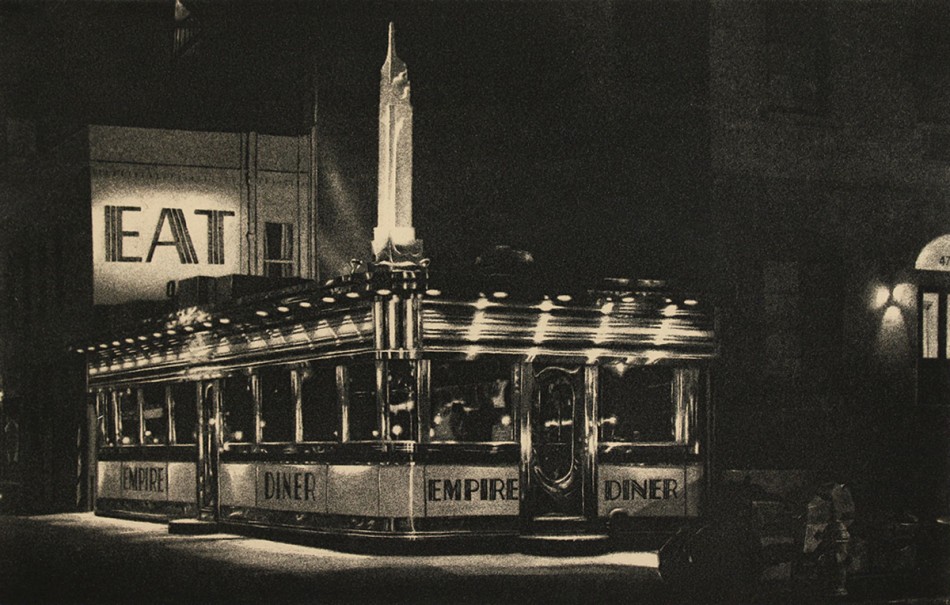

New York said goodbye to an icon this weekend. On May 14 the Empire Diner closed its doors for the last time — or rather, the first time, since this Chelsea landmark had until last Saturday night been serving locals and tourists, artists and cops, partygoers and insomniacs 24 hours a day since it opened in its current incarnation thirty-four years ago. In 1976, the diner lay closed and abandoned when it was purchased by three young New Yorkers — Jack Doenias, Carl Laanes, and Richard Ruskay — who transformed the Tenth Avenue eatery into the self-proclaimed “Hippest Diner on Earth.” The Empire Diner’s success was a prime example of the neighborhood’s renaissance, as galleries, hotels and restaurants began to pop up between the gas stations and auto parts stores which had until then dominated the landscape.

As a child growing up in the UK, I probably first caught glimpse of the Empire Diner during the opening shots of Woody Allen’s Manhattan. Later, it also made an appearance in Home Alone 2: Lost In New York, but by that time I was already all-too familiar, having gazed many times at the cover of the Tom Waits LP Asylum Years. Released in 1986, this double-album compilation featured John Baeder’s painting of the Empire Diner on its front cover. It was an appropriate choice of artwork for a Tom Waits record: the man had made a career of verbalizing bittersweet tales of urban folly to anyone who’d listen, like some down-and-out character permanently slumped at the end of the counter. Whether it was the image of the diner glistening in the Manhattan night, or Waits’ midnight rambles, I knew I had to check this place out for myself.

Years later, after moving to New York, I finally got my chance. It was a cold, November evening, and I’d arrived from the Theater District where I’d been volunteering at a contemporary dance performance. Instantly recognizable from the outside by its chrome exterior and giant “EAT” sign, inside the diner was altogether less familiar. On entering I was surprised to be greeted by a calm hush, and certainly not the usual hustle-bustle which characterizes many open-all-hours places. Instead, people spoke in soft voices and on the piano someone was playing “Song For You” by Leon Russell, making the Empire Diner the first and so far only diner I’ve ever seen with a live pianist. I sat down at the polished black counter, ordered, and gazed at the yellow cabs silently gliding up Tenth Avenue. I immediately wrote about my experience on my blog (now defunct), soon after which a certain Eileen Levinson wrote to me thanking me for my kind words. I returned with my wife the night of my twenty-ninth birthday: the overtly camp staff was hilarious and delightful. I left with a t-shirt with the “EAT” mantra emblazoned across the back. When my parents came to visit, they insisted we go to the Empire Diner for burgers.

The Empire Diner’s iconic status continued to be maintained: in March a digital image of the restaurant — drawn using an iPhone app by Portuguese artist Jorge Colombo — appeared on the cover of The New Yorker. So it was with much surprise that I learned of the imminent closure less than a month later. As soon as I heard the news I wrote to the owners, Renate Gonzalez and Mitchell Woo, expressing my shock and sadness. Renate immediately responded inviting me to the official closing party on Sunday afternoon. Arriving for the last time, I found a relaxed crowd settled on patio furniture clustered outside the restaurant, whose famous chrome glistened in the late-afternoon sun. Inside the diner, the atmosphere was decidedly more raucous, as the diner’s most flamboyant followers got down to a soundtrack of eighties club hits. There was something quite sad about seeing the last remaining survivors of a city’s much-flaunted party scene enjoying a final dance on a Sunday afternoon. This may have only been the closing of a restaurant, but what does it say about New York?

* * *

It seems not a week goes by that New York City doesn’t say goodbye to another family-run business or cherished establishment. Most of these closures go unnoticed by many, although certain blogs, such as EV Grieve and Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York, manage to meticulously document these aspects of the city’s transformation. While I strongly sympathize with the aforementioned bloggers common stance, I personally think nostalgia can be a dangerous thing, and I’m always cautious about extolling “the good old days”. After all, a lot of people were glad to see the back of them. As one commentator pointed out, “People who hate the new Times Square probably were never mugged in the old one in 1989.”

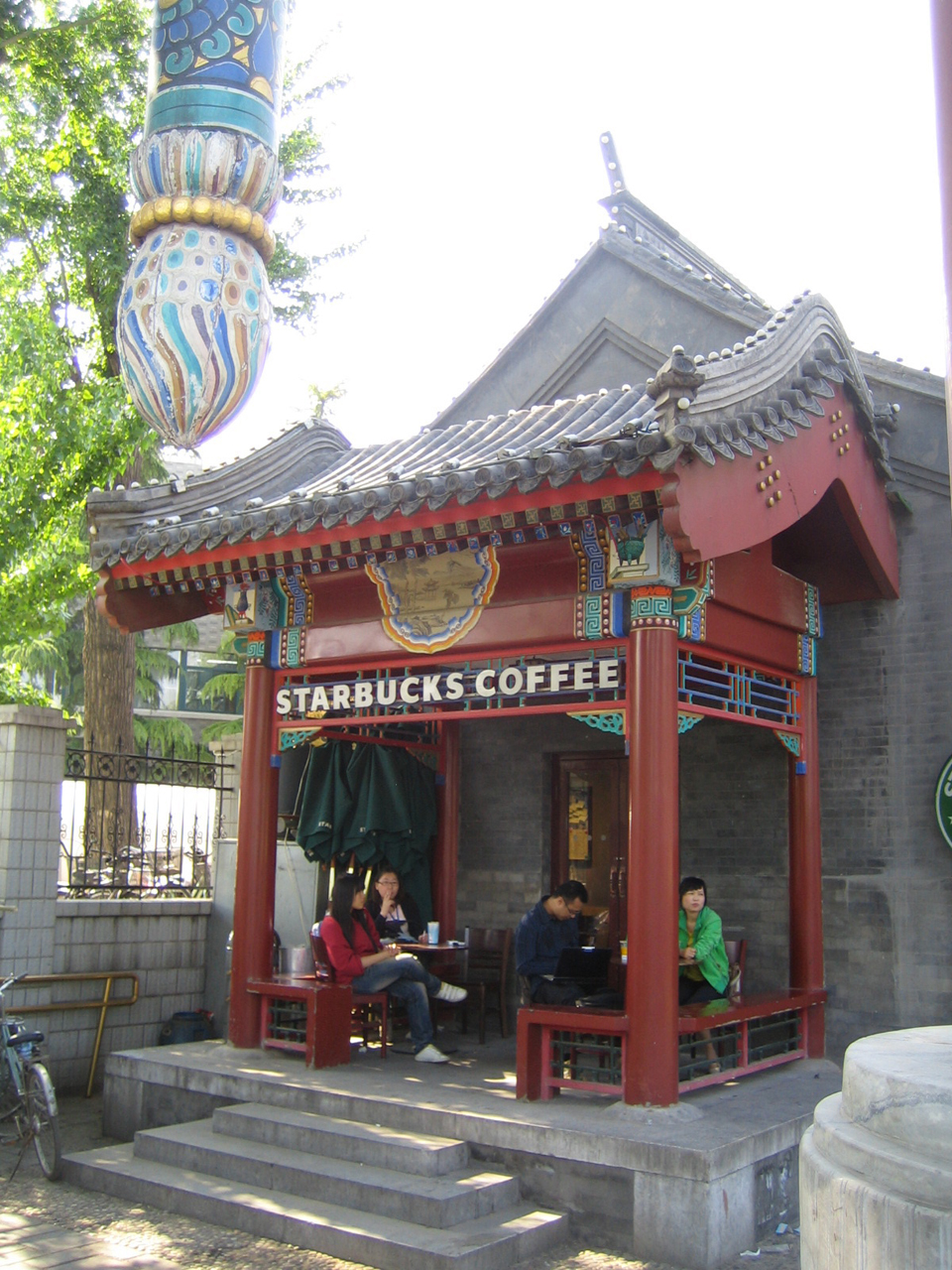

A city must always keep evolving, and nowhere is reinvention more possible than in New York. But what about when your favorite coffee shop is converted into a Starbucks? Or when the corner deli where you’ve been buying milk for twenty years is suddenly shuttered, only to reopen serving only something the kids are calling Fro-Yo? Or when an entire historic block is razed and an eco-indulgent glass condo is built in its place? I’m not alone in feeling that New York, once just a trendy, rebellious cousin to the conservative USA, is becoming victim to the steady encroachment of corporate America. Of course, this phenomenon exists the world over and is evident elsewhere — look at the state of popular music or sports — but what’s most alarming is the rapidity with which such changes occur in this millennium, particularly in a fast-paced commercial capital like New York.

New York is a city of immigrants, one which has always been driven by the arrival of new people. But in recent years, New York, in presenting itself as a desirable place to live, has gone out of its way to invite the wrong kind of transplant: a sort of suburban-urbanite, one who associates the city not with history or culture, or even crime, but with luxury and status. These are exactly the kind of people who not too long ago would have turned up their noses at Manhattan: too dirty, too dangerous, too cold. They’re the kind of people who don’t know what an egg cream is and aren’t about to try one. Sadly it seems the latest generation of adults has scant concept of a New York, or a world, pre-internet, pre-Carrie Bradshaw. I’ve met people not much younger than myself who didn’t know what the Twin Towers were until they watched them fall on TV on 9/11. If these people are the future of New York it’s not hard to understand why certain long-standing businesses are failing.

Ms. Gonzalez and Mr. Woo, while clearly saddened to be leaving what has been their place of work for the over three decades, remain philosophical. They plan to bring the Empire experience abroad and are currently looking for a future site for the diner. It wouldn’t be the first time a landmark eatery has up and left town, silently in the dead of night. The Moondance Diner closed in 2006 and reappeared somewhere in Wyoming. Last year, the Cheyenne Diner was closed, dismantled and rebuilt down in Alabama. So look out for the Empire Diner in a town near you. As for New York, like the day they decided to plant deckchairs in the middle of Times Square, it’s just another small step towards suburbia. The hippest city on earth just got a little less hip.

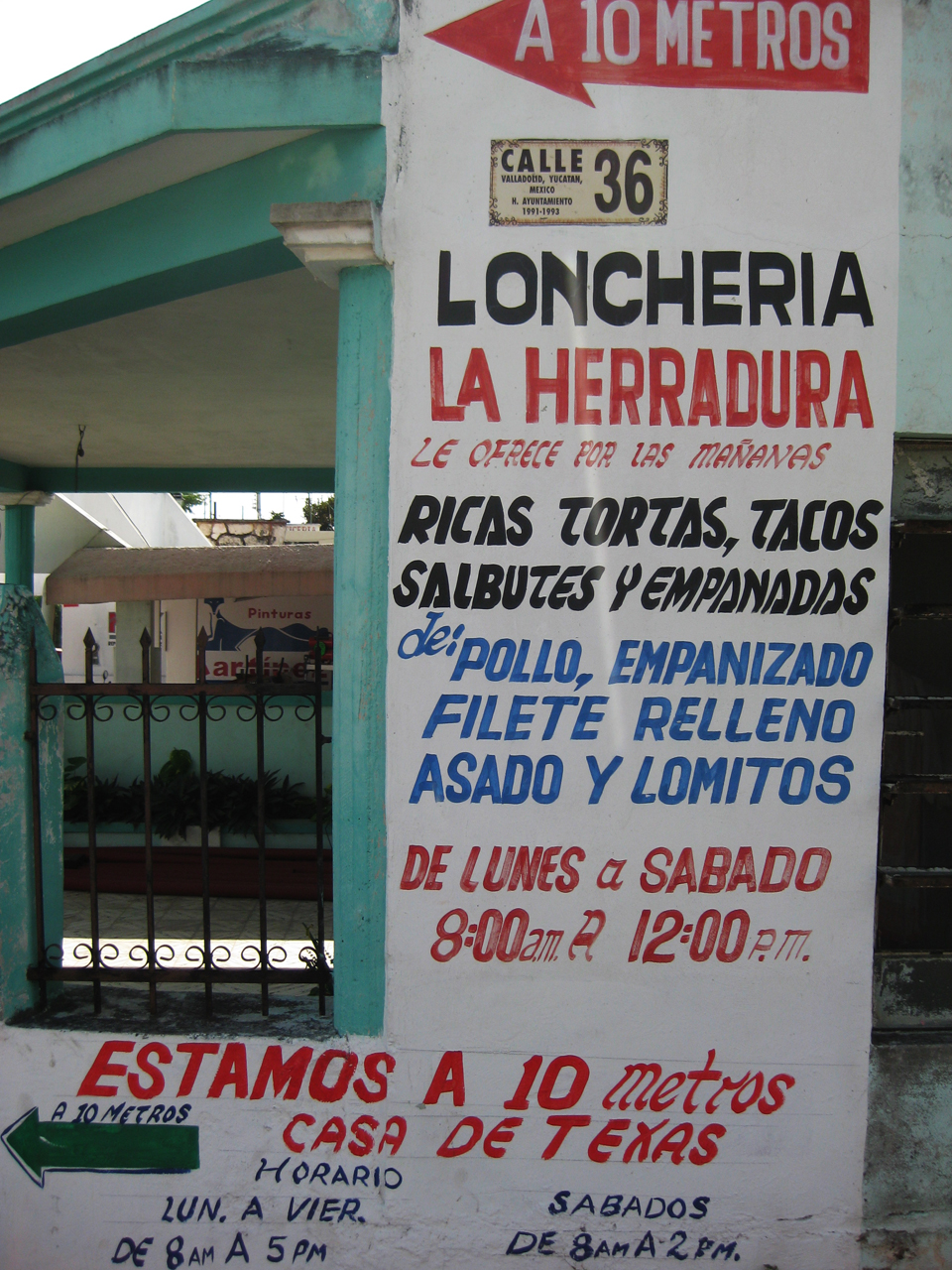

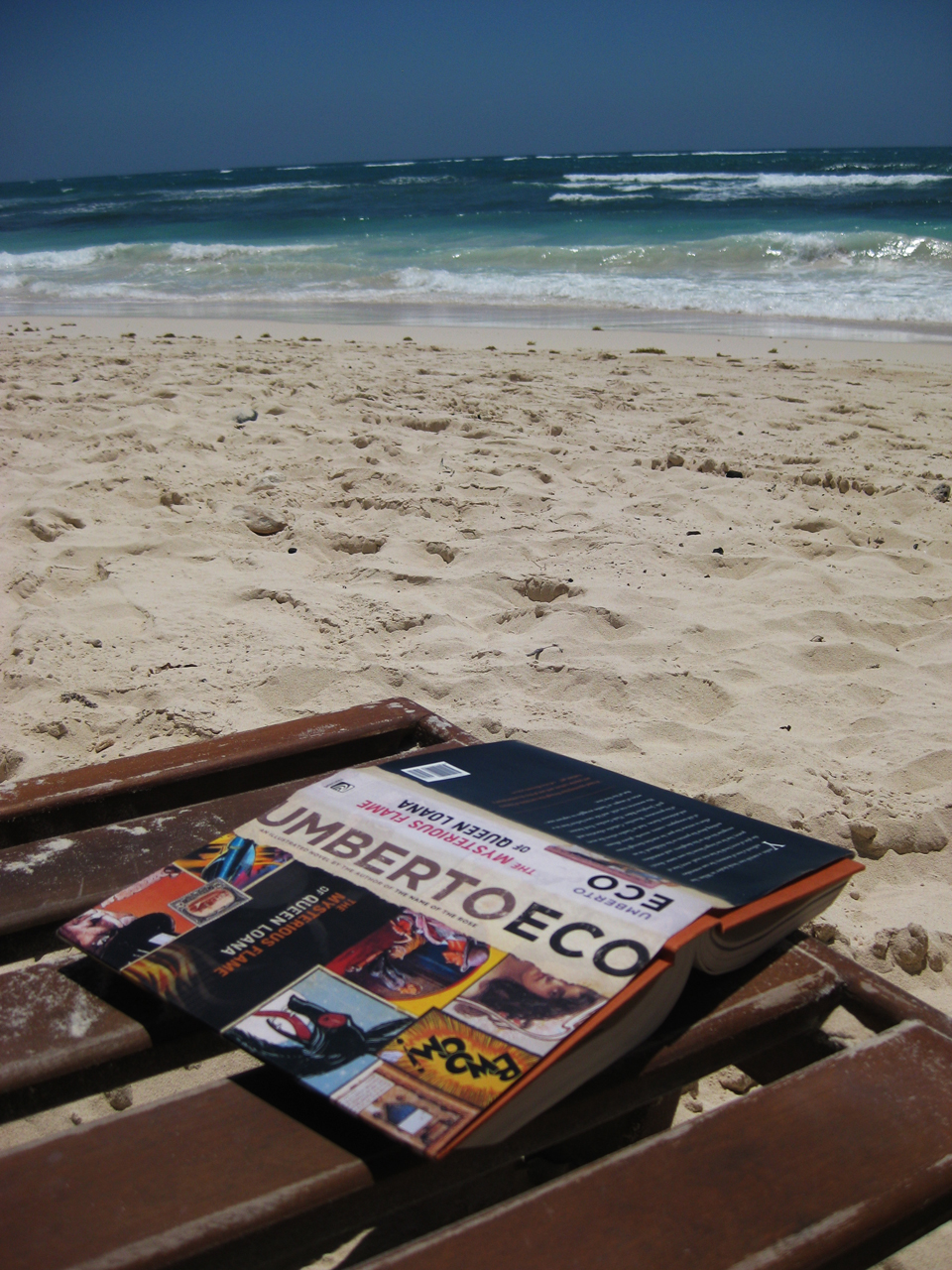

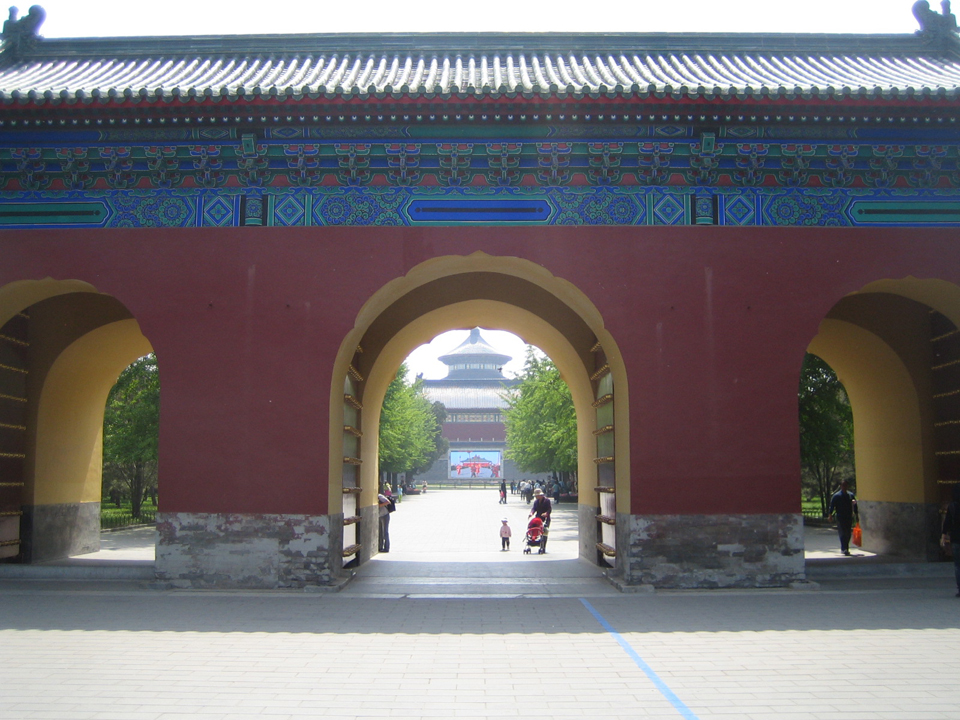

Chichen Itza and Valladolid, Yucatán, México, May 2010.

Tulum, Quintana Roo, México, May 2010.

As David Byrne once pointed out, from time to time we’re all inclined to ask ourselves, Well, how did I get here? It’s a universal feeling that strikes the hearts and minds of most adults as soon as they realize that their life is hurtling at a rate beyond their capacity to fathom. Yet as the past begins to stretch away behind me, the easier it becomes to recognize and make sense of the answer. I can pinpoint a moment in my life — a chance meeting with a total stranger over ten years ago — that rapidly sent my life in a certain direction. I can state with some confidence that the ensuing years would have been quite different had this apparently innocuous event never taken place. The funniest part is I wasn’t even there.

The unlikely setting for this encounter was Pisa Airport, officially named Aeroporto Galileo Galilei, where my parents were waiting to catch a return flight home having just spent a long weekend in Florence. If you’ve ever traveled from Pisa you’ll be aware that there’s not a lot to do there besides down an espresso or two and wait to board your plane. My parents were doing precisely that when my father happened to notice a young man across the departure lounge, for the sole reason that he was wearing a Juventus tracksuit. Dad kept his eye on him from afar, and soon discovered he was on the same flight. Though he didn’t recognize his fellow passenger as a player for the bianconeri, he wasn’t about to rule it out either. In any case he presumed he must have something to do with the famous Turin club to be dressed that way. The man in the tracksuit was traveling with another man of similar age. A teammate? A journalist? An agent? My dad usually needs little incentive to strike up a conversation with a stranger, and now his curiosity had been suitably piqued he proceeded to do just that.

Much to my father’s surprise (and perhaps disappointment), the young man did not play football professionally for Juventus, nor did he have anything to do with the club. He wasn’t even Italian. His name was Jamie and he was a former footballer from Wales who had been forced to give up the game because of injury. Now he and his plain-clothed partner, Lee, ran a football academy that offered custom soccer tours to fans and amateur youth teams. They were returning from a visit to Italy where they’d met with former Juventus striker and club director Roberto Bettega. That explained the tracksuit.

This sparked a chat about Italian football, which is when my dad happened to mention me. Evidently intrigued by my apparent interest in calcio and Italy, Jamie gave handed my dad his card and told him to tell me to get in touch. I’d graduated the previous summer and was living back at home without a job or much clue as to how to go about getting one. After hearing Dad’s story I didn’t need much prompting to pick up the phone and rang Jamie’s number. Quite what the purpose of the call would be I didn’t yet know, but the conversation quickly took on momentum when Jamie explained that he might be able to offer me some work in Italy.

A couple of weeks later Jamie and Lee came to visit me at home to fill me in on their project and discuss the idea further. They explained that they had people working for them in Milan and Rome, but their agent in Florence had little time to devote to the project now that she was raising a young family. The pair suggested I go to Florence to help her out, with a view to eventually taking over the operation throughout Tuscany. Having studied in Italy I’d been itching to move back ever since; now I had an excuse in the form of a real opportunity. I could hardly believe my luck that after months of boredom and frustration I was now being handed the possibility of a football-related job in the country I loved.

There was no game plan. Nor had there been any mention of money. Jamie had essentially done little more than ask me to go to Italy and introduce myself to his agent in Florence. Precisely what would happen after that nobody seemed to know, but with appealing alternatives not forthcoming I went along with the idea. Though completely aware that the whole thing could very possibly turn out to be a big waste of time, that wasn’t enough to deter me from finding out.

* * *

Less than two months later I found myself living in semi-rural Tuscany as the semi-permanent guest of a family-friend. When I wasn’t giving ad hoc art history lectures at the local high school or hanging out with the ragazzi at the bar in town, I was attempting to find a real job and a real apartment in Florence, and arrange a meeting with this mysterious agent of Jamie’s. Incidentally she was also Welsh, and her name was Rachel. What seemed a fairly straightforward task proved more complicated than expected, my elusive contact repeatedly postponing our plans for increasingly bizarre reasons. On one occasion she failed to show up at all, later sending me a text with the following as explanation: “I was in my Buddhism class and we were doing our chant.”

Eventually Rachel and I did meet. She came across as a fairly bubbly character, although I sensed an edgier side to her. How she’d ended up working for Jamie I wasn’t sure, but I don’t think it had anything to do with an overwhelming passion for the beautiful game. She seemed wholly disinterested in talking about the job, clearly preferring other topics such as how her husband had written a book about the life of Masaccio and was now in talks with RAI over the film rights.

Though I wasn’t learning much about Jamie’s football academy, Rachel was happy to help me out with other pressing issues in my life, such as accommodation. On one of our first meetings she took me to the American Church of St. James in Via Rucellai. She told me it was something of a hub for Florence’s ex-patriot community (I later found out that it was also where David Bowie married the supermodel Iman). Near the entrance was a small notice board with a smattering of handwritten notes left by people looking for work or roommates. Rachel suggested I leave one myself since I was looking for both. I remember thinking that it seemed a pointless thing to do, that no-one would see it, let alone respond. But Rachel was right. I needed a job and somewhere to live, and the sooner both happened the better. Later, over coffee at Caffé Giacosa, Rachel mentioned she had a friend who was looking to rent out a room in her spacious apartment in the affluent Campo di Marte neighbourhood. Not keen on the idea of sharing a flat with a bunch of students oltrarno I told her to put us in touch. A couple of weeks later I moved in with Rachel’s friend, a divorced doctor named Olivia.

Not two weeks had passed since I’d left small-town Tuscany behind that I received an email from an American student named Jessica. She’d seen my ad at the American church and wondered if I was still looking for roommates. I was amazed that someone had actually read my little handwritten note, and replied explaining that though I’d already resolved my living situation we should meet anyway. Jessica was working at the Biblioteca Nazionale, and the following Sunday afternoon invited me to a screening of Dali’s Un Chien Andalou. I sat through the film waiting for the infamous eyeball scene, all the while looking for my new acquaintance, who’d promised to be wearing a chartreuse sweater. We eventually spotted each other after the film, and after the inevitable exchange about what exactly constitutes “chartreuse” was out of the way) we took a short walk along Via Verdi where we ended up at a café called Riff Raff (I felt this was appropriate since clearly we weren’t). Jessica was not your typical Italian-American: quick-witted, funny and fascinated by the art world, she was a million miles from the provincial types with whom I’d spent the last six months routinely sipping coffee. For instance, during our first meeting she revealed that she slept on a Morrissey pillowcase. After some more correspondence I learned she signed her emails by turns “Jessicroix” and, most intriguingly, “The Director” (a reference that has never been explained to me).

The next time I saw Jessica was a week or two later in her part of town (a ten minute walk away), at a bar called Sant’Ambrogio. She was with her friend Kaitlin, a fashion student from California, who introduced herself however as “a semi-retired contortionist.” Several cocktails later we went back to Kaitlin’s place on Via dei Pilastri, a surprisingly spacious apartment filled with her own artwork, mannequins and various objets. Evidently an appropriate intake of Jose Cuervo was all our wiry host needed to come out of semi-retirement, and we were treated to an impromptu performance. Through the semi-darkness I was able to identify Kaitlin’s legs, which seemed to point in directions that defied anatomical logic. (I grew to discover that shows like this were exceedingly rare, but Kaitlin casually demonstrated her extraordinary flexibility in more mundane circumstances everyday.)

Jessica and I saw each other a few more times, but her period in Florence was drawing to an end. That September she was to embark on a masters degree in museum studies in New York. On her last evening we went to see the Botticelli exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi, and when we parted I became sad suddenly. Jessica had been my first new friend after moving to Florence but now, barely a month after we’d first met, she was gone. Such is the transient nature of international twenty-something relationships.

As for Rachel and the supposed football job, things hadn’t worked out quite as any of us had expected. Jamie and Lee did bring a small group of clients over that spring, a trip that I organized almost single-handedly. I booked their hotel in Florence, scored free tickets to a Serie A match between Empoli and Inter, and even arranged for a private visit to the Museo del Calcio at the Italian FA’s headquarters in Coverciano. Once the group had arrived in Italy I was quickly called upon to act as both guide and interpreter. While the trip was a success, similar occasions never materialized, and I slowly let my involvement in the project fizzle out. I now had a steady teaching gig and was also in the middle of writing a portion of a travel book about Tuscany.

Meanwhile Jamie no longer showed the same enthusiasm he had a year earlier. The previous September he’d flown with Lee and their families to Milan for a Euro 2004 qualifying match between Italy and Wales. After the game Jamie’s brother was crossing the street when a car struck and killed him. That spring Rachel had gone back suddenly to Wales, apparently to attend to some kind of family crisis of her own. My attempts to get in touch proved futile, and I never saw her again. Yet in a handful of short encounters she had — though quite unwittingly and unbeknownst to her — changed my life.

* * *

Kaitlin and I continued to see a lot of each other despite the departure of our mutual friend, and over the next two years she became one of my dearest and most loyal pals in Florence. For someone so outwardly eccentric, she was extremely organized and very responsible. She was an early riser and never stayed out too late, and her ability to always show up on time certainly made a nice change (this is Italy, remember). Even when I made an effort to be early I’d find here there waiting for me! Our meetings invariably involved an aperitivo, dinner, a movie at her place, or some combination of all three. Sometimes we’d go down a tiny side street around the corner to listen to live jazz at a dark and smoky subterranean boite, the imaginatively named “Jazz Club”.

A little over two years after I’d moved in with her, Olivia casually announced one morning that she was selling her apartment. Despite her suggestions to the contrary there seemed no possibility of me joining them in their new place. Not only was it further away from town, it would also be significantly smaller. While relieved to be moving out (domestic life had become strained) I’d been given very short notice to find somewhere new. When I relayed this development to Kaitlin she immediately suggested I move in with her. She was about to spend the next four weeks in Barcelona, leaving vacant her studio on Via della Pergola (where she’d moved the year before). That would buy me a little bit of time to find a place of my own. Yet again the timing had proven perfect, and I instantly took her up on her offer.

Though the two apartments were separated by just a ten-minute walk down Borgo Pinti, they may as well have been different worlds. Overnight, my freedom had been restored. I had regained control of both my schedule and lifestyle, and I found the novelty rejuvenating. When Kaitlin returned from Spain she didn’t kick me out. Instead she patiently tolerated my boxes of clutter and even gave up half of her bed. I was hugely thankful to her but was aware the situation could not continue forever, and I began house hunting with greater urgency.

One Sunday night, following a disappointing weekend of several fruitless visits to apartment prospects, I was feeling frustrated and decided to go for a short walk (we were also out of milk). In the hall I ran into a student stacking large boxes into a pile by the front door. Evidently she was moving out. When I asked where she had been living she gestured upstairs to the first floor, and told me that the landlady there now if I wanted to take a look. I hopped up the staircase and knocked on the open door. “Permesso?” I entered a large kitchen and dining area, where I was greeted by a woman in her late-thirties named Paola. She confirmed that the apartment was now vacant, before giving me a rudimentary tour. The place was beautiful, with high ceilings and old stone floors. It also had four bedrooms, which I would have to fill were I to afford to live there. Paola briefly explained the terms and the deal was essentially settled there and then. I returned to Kaitlin’s with a fresh carton of milk and a new apartment.

When I told her about what had happened Kaitlin asked to see the place for herself, and didn’t think twice about moving in with me. Her studio was on the ground floor and I think she was tired of living alone. We’d now have to find only two roommates. The city was permanently littered with announcements advertising apartments, which were usually designed with those little tear-off strips containing the relevant contact details. So I set about making my own. Rather than risk having our flyer become lost in the sea of tatty typed documents, I hand-drew the poster myself, describing Kaitlin as a “fashion student/contortionist” and myself as an “English teacher/writer/deejay” (I had recently begun spinning discs at a popular local watering hole). I threw a stack of freshly-printed flyers and two hefty rolls of masking tape into the basket of Kaitlin’s bike and set off, stopping every few feet to tape our ad to every lamppost, phone booth or billboard that I passed.

My supply of posters severely diminished and my hunger mounting, I returned home for lunch. I’d finished eating and was about to ignite the Bialetti when the phone rang. I picked it up and an American woman’s voice spoke to me. “I saw your poster,” she said, before quickly adding that she was interested in seeing the apartment. It worked! I asked her a little about herself. She was studying Italian Literature at the university and currently commuting from Bologna. Previously she’d lived in Barcelona, to which I immediately jumped on the fact that had Kaitlin had too. We arranged for her to come by the following day. I took down her phone number but almost forgot to ask for her name. It was Hillary. I hung up and returned to my coffee, blissfully unaware that I’d just had a first conversation with my future wife.

Hillary arrived as planned the next day and moved in the day after that. Kaitlin and I liked her immediately, and a rudimentary online search of her name (more out of curiosity than a need to background check) produced only one result: a photo of her playing jazz vibes taken in Jamaica. Such evidence was enough to reassure me that I’d made a good decision. After living with Hillary for a few days I grew increasingly happier that she’d walked into my life. Out of the rolling mountains of West Virginia she had already packed in a lifetime of exotic adventures. In addition to her recent experience in Barcelona she’d spent some of her high school years in Seville, and had also lived in Hungary and Cuba. We shared a lot of tastes: she sang opera and knew a lot about music, especially jazz. Most endearing of all was her love of cheese and preference for drinking Campari Soda straight from the bottle. As was perhaps inevitable given our shared quarters, Hillary and I began an accelerated journey towards domestic routine. It began with one making the other coffee, or a bowl of pasta for lunch. Soon we started going to the supermarket together. Then one afternoon, as I stood pressing a shirt, she dumped a stack of her own clothes for me to iron.

I was the happiest I’d been since arriving in Florence; in the space of a couple of months my life had once again changed dramatically, and for the better. We had such fun in our new place that we soon nicknamed the apartment “Il Teatro”, both as a nod to the famous theatre a few doors down and to the Felliniesque scenes of rampant intellectual debauchery to which we aspired to play host. We threw a long overdue housewarming party in October, after which Hillary and I stayed up until dawn. As we finally retired to our separate rooms she gave me precise instructions as to when she wanted to bring her coffee in the morning. She may have been only half-joking, but when she saw me place the tray down next to her bed at the requested hour it must have been a turning point.

* * *

In December Kaitlin left Florence for good to return to Barcelona, leaving Hillary and I on our own with two roommates, neither of which — for one reason or another — were the easiest of people to live with. Thank God we had each other. We retreated into ourselves, and decided to move out in the summer. We ended up moving in with an acquaintance of mine who sold leather jackets on San Lorenzo market (he’d also deejayed with me before). His apartment was on the top floor of an old building in Via Porta Rossa, literally around the corner from Piazza Signoria. Moving out of Il Teatro into the next apartment was not easy. I arrived home in the late afternoon having just got back from Rome, where I’d spent the week giving art history tours to a group of Mexican high school students. Hillary and I then spent the night carrying our belongings on foot to the new place, which was in a building so old its narrow stone staircases had been unevenly worn smooth through centuries of use, making them all the more arduous. When we eventually completed the job around dawn, Hillary immediately cracked open a beer. We then staggered into the nearby bar for breakfast. Catching a glimpse of myself in the pasticceria’s elegant mirror I was horrified: I looked like death warmed up, and began to seriously wonder what the hell I was doing with my life.

Though I still loved Florence, I felt like I’d outgrown it, and my life there was becoming a parody of itself. For as much as I enjoyed drinking Campari or reading la Gazzetta with an espresso I was barely surviving. Meanwhile, in New York, Jessica had completed an internship at the Museum of Modern Art. On a whim, I applied to the same program myself, and towards the end of the summer they called me up. The next thing I knew I was armed with a J-1 visa on a jet bound for JFK.

Somewhere over the Atlantic, as I anxiously pondered what I was in for stateside, I started to look back at where I’d been. For the first time I was able to trace the most significant events of the last few years back to that meeting between my parents and Jamie at Pisa Airport. As an ardent Fiorentina fan, it pained me almost to concede the role that Juventus had played in the proceedings: