The other day I came across a tatty copy of New York magazine dated June 15, 1987. The cover story was entitled “The Buildings New Yorkers Love to Hate”, a list of the city’s most unpopular architectural landmarks which included the World Trade Center and the former PAN-AM Building. Most remarkable however, were the local listings towards the back of the magazine. The Restaurants section included just three eateries for the whole of Brooklyn. If you’ve been to Brooklyn lately this may seem hard to imagine, though if you were around in the late-eighties probably not quite so much. Indeed, the first time I visited New York eleven years ago it never even occurred to me that I might even venture across the East River.

When they hear the words “New York”, most outsiders think of Manhattan, and who can blame them? After all, when Frank Sinatra sang, “If I can make it there I’ll make it anywhere,” he wasn’t talking about Red Hook. Many visitors mistakenly consider Brooklyn another neighborhood, when it is actually New York’s most populous borough and existed as an independent city until 1898 (today it would still rank as America’s fourth largest). But no-one ever crossed the Atlantic with aspirations of making live hummus in Carroll Gardens.

But suddenly it seems Manhattan is no longer where it’s at. Indeed, if you believe everything you read, you’ll be told that Brooklyn is now everything Manhattan once was: cool, exciting, edgy. In short, the place to be. Before we go on I should make one thing clear: I’m not talking about the Brooklyn of Coney Island or the Dodgers or even Spike Lee; I’m talking about New Brooklyn. New Brooklyn looks a lot like old Brooklyn, except it’s a bit prettier and a lot more expensive. Though New Brooklyn garners plenty of media press attention, nobody does a greater job at promoting New Brooklyn than the New Brooklynites. The New Brooklynites are easy to spot. They are usually white, might have a beard, and definitely don’t speak with a Brooklyn accent. If you meet a New Brooklynite there’s a good chance they will soon tell you how glad they are to be living in Brooklyn, and how you really should be living there too.

Call me a contrarian, but when someone strongly urges me to do something, my natural inclination is to not do it, even if my original instinct might have told me otherwise. Maybe I’d have moved to Brooklyn by now if it weren’t for all those Brooklyn dwellers recommending I do so as soon as possible. Even my boss (who lives in Brooklyn) will regularly bring up the question as to why I’ve yet to move there, imploring me to “get off the grid”. I sometimes imagine he would enjoy enormous satisfaction were I to transfer out to Ditmas Park, so I too can endure an hour-long commute on the Q train at the cost of $89 a month. Many people who live in Brooklyn still work in the city; by living in Manhattan I currently use the subway only once a week at most, so I’m already saving money plus two hours out of every workday.

Much of the problem regarding the Manhattan-Brooklyn divide is definitely psychological, a syndrome by which I am affected as much as anyone else. I can be in Park Slope almost as quickly as it takes me to reach upper Broadway, yet I wouldn’t think twice about hopping on the 1 train up to Zabar’s for a cinnamon babka. Ask me to schlep out to Brooklyn and I’ll pull out a list of excuses.

Certainly Brooklyn’s rapid, ongoing transformation and continuing cultural divergence from Manhattan is arguably one of New York’s most significant changes of the last twenty years. There are several factors which New Brooklynites will always cite when discussing the advantages to their borough. The first usually concerns the lower overall cost of living. Yet while a railroad apartment in Bushwick may be considerably cheaper than a two-bedroom in the West Village, as New Brooklyn continues to generate hype so its rents in the more desirable (and exclusive) neighborhoods become comparable to those in Manhattan.

Such areas are also epicenters of Hipsterdom, an alarmingly unimaginative subculture whose primary concern is appropriating aspects of bygone eras and passing them off as its own. Skinny jeans, horn-rimmed glasses, plaid shirts and ironic facial hair: these are the cornerstones of the young New Brooklynite’s carefully cultivated wardrobe, items which must be worn at all times with the nonchalant attitude of someone who isn’t really trying. It also helps if you have some tattoos (you can almost guarantee that most of these people had very dull parents). Most hipsters look like they haven’t seen a gym — or the sun for that matter — since they left their altogether drearier hometowns (which to be fair probably wasn’t all that long ago).

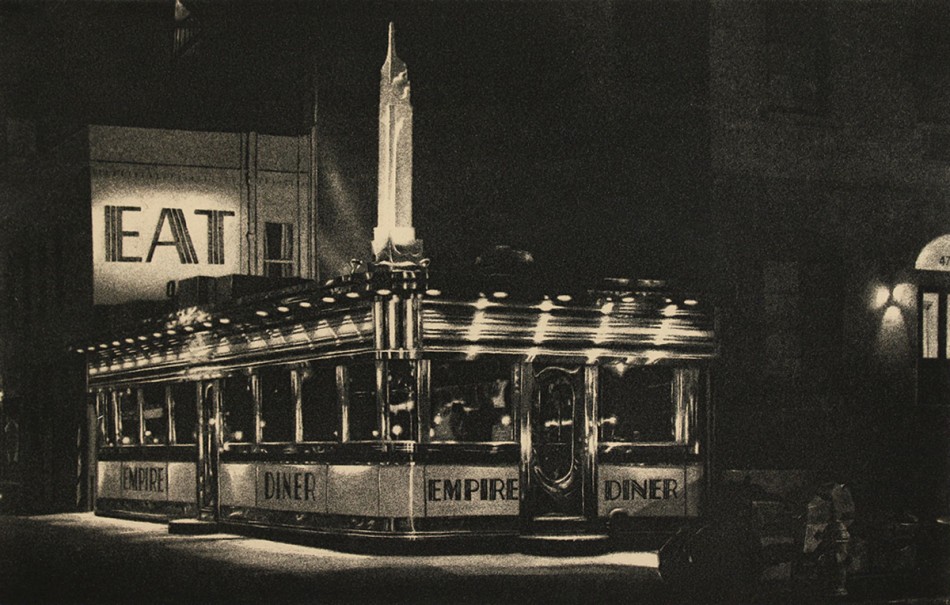

Manifesting itself through music, fashion, even food, New Brooklyn has in recent years developed its own brand of taste and style that often appears a deliberate antithesis to Manhattan’s urban brashness and cutting-edge commercialism. Small businesses label their products as hand-crafted, home-made, organic or artisanal, in an attempt to differentiate themselves from the giant, soulless corporations which proliferate across the river. Yet the sheer number of like businesses which have cropped up over the last couple of years only diminishes their collective value. Suddenly it seems, every kid in Williamsburg is making Prohibition-style soda while attempting to grow a moustache. The appropriation of this down-home folksiness is clearly an attempt to lend weight to fleeting projects by referencing something real. In this sense Brooklyn is the crafts to Manhattan’s Arts. But as it continues to bemoan Manhattan’s so-called superficiality New Brooklyn has unwittingly created its own culture which is no less manufactured. At least Manhattan isn’t bullshitting anybody, and I’ll take an egg cream and a tuna melt any day over a gluten-free vegan cupcake.

I don’t wish to suggest for a minute that most of those who love Brooklyn aren’t genuinely happy living there, or that everyone should want to live in Manhattan or feel unhappy if they are not. Manhattan is definitely not for everyone, and of course, there is nothing inherently wrong with eating local or buying homemade, except for the holier-than-thou attitude that too often accompanies these ideas and lifestyle. Like the vegetarian who pulls a face when you order steak, the worst kind of New Brooklynite takes on an air of tremendous self-righteousness when you confess to enjoying the simplest of pleasures, as if drinking non-microbrewery beer could jeopardize your friendship. New Brooklynites’ constant praising of their borough can sometimes come off as obsessive, and in extreme cases it seems like an inverse reaction to not living in Manhattan, as if they are grappling with some trauma. Maybe they’re irked by Manhattan’s history of condescension towards the “outer boroughs”. Or maybe the very act of living in Prospect Heights gives them a warm fuzzy feeling of satisfaction akin to donating money to Africa or buying a T-shirt to benefit Haitian earthquake victims.

* * *

Of course, these phenomena are by no means exclusive to New Brooklyn’s population, but rather representative of the white, middle-class youth of America. Indeed, we are already witnessing the commodification of “New Brooklyn” as it enters the corporate mainstream. Take for instance the common brand of twee, faux-naïve songs which now permeate movie trailers and national television commercials for some of America’s biggest companies. In this week’s New York magazine (which incidentally lists nine restaurants in Williamsburg alone), Adam Sternbergh identifies every large city in the Western world as having its own Brooklyn, specifically a neighborhood with “nice blocks, good restaurants, and beards.” That the new Brooklyn can be defined so succinctly conveys everything about its limitations and its arch self-awareness. New Brooklyn, its look and sound, is now being used to sell everything from Japanese hybrids to portable e-book readers. Perhaps the most significant event in this trend was the launch of a “Brooklyn-themed” bar/restaurant set to open this autumn in — you guessed it — Manhattan.

That there are people who feel the need to define “New Brooklyn” — through its cuisine of all things, and on Manhattan turf — says a lot about the borough’s pervading complex of inferiority. It’s also in complete contrasts to the island’s greatest strength of total defiance and utter indifference. Manhattan cannot be tamed, and somehow manages to resist the waves of social or economic change. Sternbergh argues that it’s Brooklyn’s supposed positive qualities which make it so obnoxious, and that the same phenomenon could never happen with Manhattan because “they only ever made one Chrysler Building.” Manhattan could never become a brand because its brand is too vast, too diverse and far-reaching, Movies, art, jazz, tourism: these are things that are too beloved and universal to be considered “cool” anymore.

Though separated by a small body of water called the East River, Manhattan and Brooklyn can at times appear like two worlds in the same city, of which their inhabitants are two very different species. From its breathtaking verticality to its teeming street life, Manhattan, more so than any other major city, is a direct result of its geography. While Brooklyn and Queens are still home to some of New York’s largest ethnic communities, Manhattan’s cosmopolitan population is forced to exist on a narrow twelve-by-two-mile island. This tremendous concentration of people, their different cultures and languages, is what gives the city its unique, relentless energy, and in extreme cases can breed bouts of aggression or creativity, sometimes in the same breath. It’s these immovable confines which have helped make self-absorption and ambition two of the most common traits among Manhattanites — without space to move outwards, the city can only look inwards and upwards.

All of this has enabled Manhattan’s inhabitants to consistently defy categorization and stereotype as they go about their daily lives. They rarely question their presence on the island — many seem to live in a self-imposed exile of sorts, and are often unable to imagine themselves anywhere else. Though often perceived as neurotic or narcissistic, the truest Manhattanite is a model of fierce independence, flagrant individuality and unwavering positivity. To stroll the city streets is to experience a warm, unspoken understanding — a camaraderie among strangers, an unlikely mutual respect between all those who share a sidewalk.

Yet for many Manhattanites, moving to Brooklyn is seen almost as an urban rite of passage, an inevitable step in the life of a New Yorker as young adulthood gives way to parenthood, and that Chelsea studio suddenly becomes untenable. But for now, my favorite reason to visit Brooklyn is the ride home as the N train trundles over the Brooklyn Bridge. Downtown skyscrapers soar into view, my pulse quickens and I am thrilled at the thought of my apartment nestled hidden somewhere within all of that brick and concrete. Why would I want to be anywhere else? Perhaps Tom Waits put it best when he was asked to describe New York. “Well, it’s like a big ship,” he said. “And the water’s on fire.” I’m not quite ready to jump ship just yet.

Film stills from “Manhattan”, 1979 (United Artists).