As intrinsically associated with Manhattan as fire escapes and pretzel vendors, New York’s yellow taxicab’s icon is rivaled only by the Empire State Building or the Statue of Liberty. But when Mayor Michael Bloomberg unveiled The Taxi of Tomorrow back in May, ending months of speculation as to the future of this ubiquitous presence on the city’s streets, he brought an untimely end to decades of sunshine-colored style and swagger.

Of course, you’ll still be able to hail a yellow cab, but a few years from now it won’t be a Crown Victoria with aged tires and temperamental brakes. Sure, the driver will still be a cranky foreigner who always insists on taking Sixth Avenue, but he’ll be behind the wheel of a Nissan NV200 minivan, the winning car in the city’s Taxi of Tomorrow design competition. The Japanese manufacturer beat out similar concepts from Ford and Turkish company Karsan, earning itself a ten-year contract to provide New York with some 13,000 taxis starting in 2013.

The NV200 is not New York’s first minivan taxi: similar designs were introduced as early as 1996. Since the 1960s the Taxicab and Limousine Commission has leaned heavily on the Chevrolet Caprice and Ford Crown Victoria, which for decades vied for fares alongside the iconic Checker, the last of which did not retire until 1999 (though production stopped in 1982). The current version of the Crown Victoria has become something of a classic in its own right, having been on the road since 1998. However, in the last few years an increasing number of alternative vehicles have joined the fleet: as of 2011 there are seventeen approved taxi models in New York City, some of which have hybrid motors, though the Crown Victoria still represents 60% of all New York cabs. Aside from offering a smoother, comfier ride, it has endured precisely because it looks and feels like a taxi should. Unfortunately Ford retired the model earlier this year, hence the need for a replacement.

Crossing 23rd Street near Madison Square Park today I happened upon a public display of the Nissan NV200, a pop-up exhibit located in the shadow of the Flatiron Building, in the new pedestrian area that until recently was part of Fifth Avenue. At first sight, the winning vehicle appeared to possess one fatal flaw: nobody will want to be seen dead in it. An awkward oblong with an extra-high ceiling and sliding doors, the car belongs in the kind of suburban town people once came to New York to flee from. By 2019 all New York taxis will be the NV200, which already looks set to go down in history as an eyesore on the city’s roads and a running joke among New Yorkers — though in an unfortunate twist its imminent ubiquity will mean the joke is on them.

The NV200 has sparked further controversy over the fact that this state-of-the-art vehicle is inaccessible to disabled passengers. Naturally, the city is keen to draw attention to the taxi’s partial-electric motor, high fuel efficiency and host of revolutionary features, which include a panoramic sunroof throughout the whole back seat, passenger airbags, anti-bacterial non-stick seats, independent passenger climate controls and passenger charging stations –- one outlet and two USB ports.

This list of specifications is indicative of how New York’s priorities have become skewed. Yes, we live in a fast-paced city that supposedly never sleeps, but who needs to plug in a laptop and charge an iPhone in a taxicab? The fact that we have convinced ourselves otherwise says everything about our disengaged, entitled society and the people running it. Though it may have nothing to do with the New York we think we know, the unfortunate reality is that the Taxi of Tomorrow is perfectly in keeping with the New York of 2012. This is just the latest episode in Mayor Bloomberg’s corporate crusade to eliminate character and individuality from the street and transform the city into a luxury playground destination for the rich and famous (or just plain rich).

After an initial plan to equip all taxis with hybrid engines was quashed, in 2008 New York cabs were given a fresh look, including new door decals (which replaced the old stenciled “N.Y.C. TAXI” lettering) and an official logo. Created by Swiss graphic designer Claudia Christen, the new branding even featured handy instructions on how to hail a cab, in the form of a stick man with his arm raised.

The first sign that taxi rides themselves were to be disrupted was the 2008 mandate for the insertion of a small television screen into the backseat, a pointless and universally despised device with a particularly rebellious touch-screen OFF button. Its presence ensures that each passenger is routinely greeted with the jolting theme from ABC’s Eyewitness News moments after getting comfortable. Admittedly, there are few places left in the world that televisions have yet to infiltrate, but this so-called Passenger Information Monitor (or PIM, as nobody calls it) conveniently doubles as a credit card payment machine whose functionality rate tends to hover just above fifty percent. Of course this will all seem quaint once the NV200 has rolled into town, complete with its 15-inch television screen, suggesting it perhaps also offers a choice of the latest movie releases on demand.

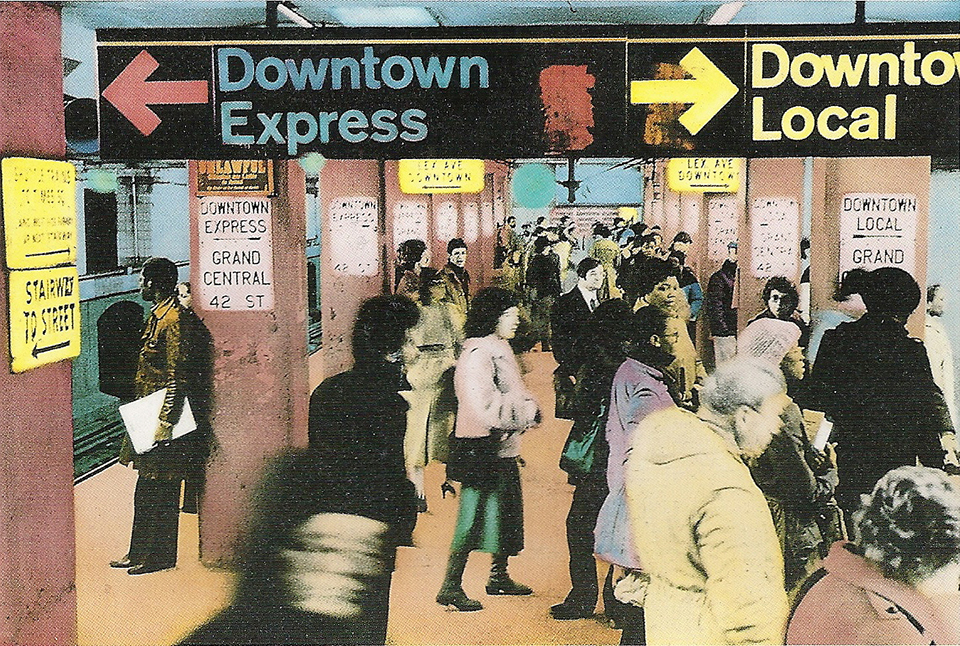

Unwanted accoutrements notwithstanding, for me the New York taxi experience has yet to be tarnished. My favorite thing about riding in the backseat of a cab is that you are treated to so much of the city and so many aspects of urban street life — not to mention myriad architectural marvels if you sink in your seat — flying by in a matter of minutes. But many are oblivious to what’s whizzing past their window, and miss it all because they’re too busy consulting an app to tell them the quickest route to the Bowery Hotel.

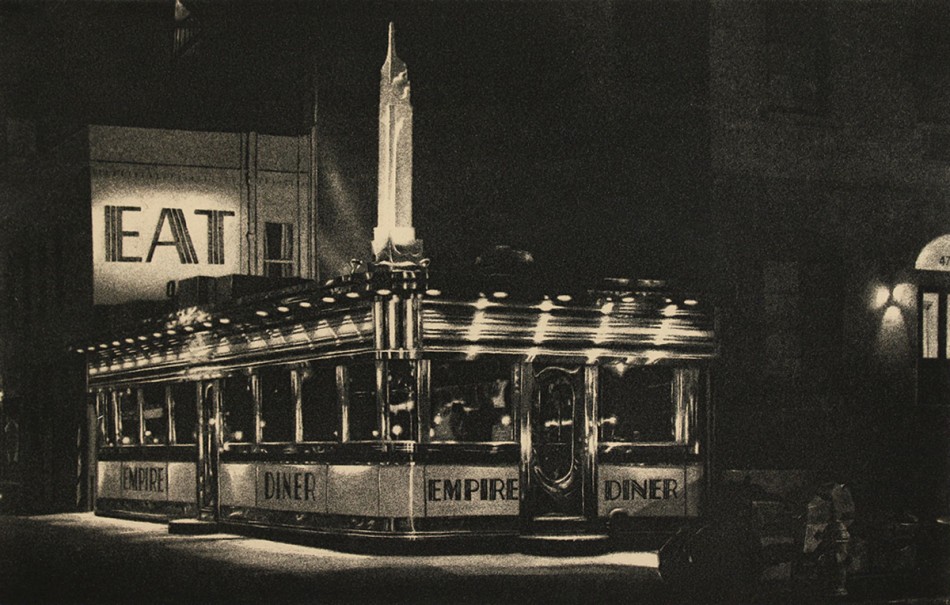

I remember the first time I walked out of JFK Airport and stood in line for a taxi to take me to Manhattan. That cab ride was and remains the most intensely memorable one-hour car journey of my life. But if I’d been asked to step aboard a Nissan NV200 I may have opted for the subway. I’ll never forget the sense of power I felt when I hailed my first cab one evening on Central Park South. I still take great comfort in watching the endless, steady stream of taxis gliding down the Avenues at night. Today the few Checker Cabs still running on Manhattan’s streets are used to advertise banks or chauffeur newly-weds, but on the rare occasions when I spot one — parked on a shady street or speeding uptown — I can never quite believe my eyes. It’s like a glorious dream.

Years from now, when the Taxi of Tomorrow has become the taxi of today, immortalized in a thousand movies, will it provoke a similar emotion? Or will people be turned off by the predictable mirror-image of their own suburban existence? New York’s rapid transformation over the last ten years has the potential consequence of coming full-circle: sooner or later the city will finally stop being desirable for the precise same reasons it became desirable (again) in the first place. It will have become too safe, too clean, too un-different. Maybe then — and only then — they’ll bring back the Checker.