In Italy they call him “il Vecio”, the old man. But in 1982 Italy coach Enzo Bearzot was a tanned, lithe 54-year-old in the prime of middle-age, a newly-crowned world champion who had led his team to the most unlikeliest of achievements. The nickname (from his native friulano) never had much to do with age but rather a unique Italian personality. Cool, educated and deeply spiritual, Bearzot was an icon of the Italian game who in some ways seemed to belong to another time. An avid fan of music and literature, before the World Cup celebrations had even subdued he’d already hopped a flight to New York to hit some jazz clubs. As a football coach he was incredibly self-confident but never arrogant, instilling in his teams “la forza del gruppo” or group strength, a model on which all top sides are today built. Though he made occasional contributions to La Gazzetta dello Sport, in the final months before his death in Milan yesterday Bearzot only left the house to attend mass or buy the newspaper. Il Vecio had finally become an old man.

Coincidentally, Bearzot died on December 21 just as Vittorio Pozzo — who masterminded Italy’s first two World Cup wins in 1934 and 1938 — had forty-two years ago. Yet nothing about Bearzot’s unremarkable playing days hinted at the success that awaited him as a World Cup-winning coach. Born in Aiello del Friuli in 1927, Bearzot enjoyed a modest footballing career with Inter, Catania and Torino. His role was that of defensive midfielder, known in Italy as mediano, an unfashionable position generally reserved for those blessed with a strong willingness and work ethic rather than any particular flair or natural skill. Over the course of eighteen years he earned just one appearance for the national team, in 1955 against Hungary in Budapest. Italy lost the match, but the Italian marked the legendary Ferenc Puskas out of the game.

After “una vita da mediano” he quit the game in 1964 and immediately went into coaching, beginning as an assistant at Torino before taking over at third division Tuscan side Prato. Prato’s ninth place finish in Serie C Girone B at the end of 1968-69 season would be his last involvement with club football. Instead Bearzot fell into the fold of the national team, with which he embarked upon a seventeen-year odyssey that saw him rise to a role of true protagonist in a period marked by various disappointments and one unforgettable accomplishment.

Bearzot coached Italy’s under-23 side for six years before being brought in to assist existing national team coach Fulvio Bernardini in 1975. Essentially it was Bernardini who remained as Bearzot’s assistant until 1977, when the Friulan unabashedly took sole control with a World Cup less than a year away. Some accused him of weaving a takeover plot behind Bernardini’s back, and skeptics continued to cite a lack of experience as Italy prepared for the 1978 World Cup in Argentina. Bearzot’s slim CV did not seem to overly concern him: “You don’t need a degree in cibernetics to coach the national team,” he once retorted. Though he’d never coached in Serie A, he was already a veteran of two World Cups, having travelled as assistant coach to Ferruccio Valcareggi to Mexico in 1970 and West Germany in 1974.

Criticism rarely bothered Bearzot. At Rome’s Stadio Olimpico, during Italy’s final friendly match before the 1978 World Cup, he had endured chants of “Sce-mo! Sce-mo!” (Stupid! Stupid!) directed at him by the few thousand fans who’d shown up to support a sterile national team. But though he claimed to give little weight to popular opinion, Bearzot’s inclusion of the youngsters Antonio Cabrini and Paolo Rossi in his 22-man squad suggested the coach had finally succumbed to outside pressure (a theory he always denied). Surprisingly, on the pitch it mattered little. In Argentina an attractive Italy side beat France and the hosts before eventually losing in a third-place play-off, a fourth-place finish they equalled two years later at the European Championships held in Italy. Despite the usual reservations, Italy produced arguably the best football of both tournaments. The 1982 World Cup was still two years away, but the groundwork for that remarkable victory had been laid.

Though Italy’s win in Spain came as a beautiful surprise to most, Bearzot exuded a calm confidence from the outset. “I believe in the spirit I’ve infused in my group of players,” he said, a month before the tournament started. “I’m convinced we might struggle against Poland, Peru and even Cameroon, but we’ll do much better in the next round. In the end my winning mentality will triumph.” However prophetic this statement would prove, to his closest confidants the coach confessed to feeling like Gary Cooper in High Noon: a lonely man with the entire world against him. Not even he anticipated just to what extent Italy would struggle during the group phase, managing only to grind out three uninspiring draws.

Not for the first time, Bearzot’s selection process had raised eyebrows. A preference for Paolo Rossi was primary cause for concern. The striker had shone in Argentina four years earlier but had missed the last two years following a ban from football for his alleged involvement in a betting scandal. Meanwhile Serie A’s top scorer for the last two seasons, Roma’s Roberto Pruzzo, had failed to even make the squad. On such matters il Vecio was typically of one mind. “Gossip, rumour, Italian chitter-chatter,” he said, dismissing accusations. “I don’t chit-chat — that’s what makes me different from other Italians.” Tension with the Italian media had reached an all-time high, resulting in Bearzot’s enforcement of an infamous silenzio stampa which vetoed all outside communication. Many still point to this unprecedented act as the turning point in Italy’s campaign, as it allowed the players to train in peace and focus on their path to glory.

In the second group phase Bearzot’s decisions were quickly forgotten as a revitalized Italy disposed first of holders Argentina, and then tournament favourites Brazil in a match which many still rank as the greatest ever. Stopper Claudio Gentile was praised for effectively marking (by any means possible) Maradona and Zico out of both games. Paolo Rossi scored a hat-trick against Brazil and two more goals in the next match as Italy brushed aside Poland in the semi-final. Suddenly, Italy were in the World Cup final against a bulky but tired West Germany, and by the time his team took to the field in Madrid’s Estadio Santiago Bernabeu Bearzot’s confidence in himself and his players had peaked. Not even Cabrini’s first-half penalty miss could veer the ship off its course.

What followed on the evening of July 11th 1982, has entered into Italian footballing folklore, and the sights and sounds of that night in Madrid are etched upon the country’s national consciousness. Marco Tardelli’s crazed sprint following his team’s second goal (to this day referred to in Italy simply as “l’urlo”), President Sandro Pertini (who many observers called Italy’s political answer to Bearzot) waving his arms in the stands, RAI commentator Nando Martellini’s triple cry of “Campioni del mondo! Campioni del mondo! Campioni del mondo!” at the final whistle, the famously documented game of cards on the plane home. After netting his sixth goal of the tournament in the final, Rossi finished the competition as winner of the Golden Boot. “I am what I am because of him,” he said today of Bearzot. “He was like a father to me.”

When the final whistle blew in the Bernabeu, Bearzot turned to his assistant coach Cesare Maldini and yelled, “I’m never leaving the Italy bench! I’m never leaving it!” After such a long and strained rapport with both press and public, the temptation for many would have been to bow out as world champion and national hero. But Bearzot had forged a rare and oddly personal bond with his country’s national team, to which he always remained connected and associated more than to any club. Despite the tournament’s happy ending he refused to forgive his detractors, who now invited the victorious coach to speak at the post-match press conference. “Don’t you have any more questions for me?” was his response. Of course, leave his position as coach he eventually did, four years later after the World Cup in Mexico, where a lethargic-looking Italy’s lacklustre defence of their title saw them topple to European Champions France in the last sixteen. This time Bearzot had relied too heavily upon the players who’d excelled in Spain, and a cycle which had begun eleven years and 104 games earlier, had finally come to its inevitable conclusion.

* * *

Such tenure at the helm of one of toughest jobs in soccer would appear unthinkable in today’s footballing climate of instant gratification and knee-jerk reactions. Instead it took Bearzot seven years to win over press and fans, and then only after having claimed the sport’s ultimate prize, after a forty-four-year wait. It was a victory for a team which spanned generations. For forty-year-old captain Dino Zoff the World Cup put the seal on a terrific career. Zoff had made his Serie A debut before the teenage Giuseppe Bergomi was even born; the Inter defender only retired in 1999. The success helped galvanize a nation that was still reeling from the anni del piombo, a bleak and tumultuous period in Italian history characterized by social turmoil, political corruption and violent acts of terrorism. For once the Italian people were united in a wholly positive way, and the country entered a period of fresh hope and economic prosperity which continued for most of the rest of the century.

The performance in Spain dispelled many attitudes towards the Italian game, reversing a trend for defensive catenaccio-based tactics which had prevailed since the sixties. Few goals in World Cup finals involve two defenders exchanging passes in the opposition’s penalty box, but Bergomi and Gaetano Scirea did exactly that before laying the ball out to Tardelli to drive home perhaps the most memorable goal in Italy’s World Cup history. By the mid-1980s Italy had become football’s spiritual home thanks in large part to a sudden influx of new money and world talent, a period for which the 1990 World Cup held in Italy was an apex. Only around the turn of the millennium did this view of Italian football shift back again, as the game in Italy began to be viewed with less praise than scorn. By the time the Azzurri conquered the world again in 2006, the bubble that started with Bearzot had burst.

Parallels between Italy’s World Cup feats of 2006 and 1982 are obvious. Both were born out of the rubble of domestic scandal, while both coaches relied on a collective group strength rather than the talents of any one individual. Sadly, there were also similarities in the way both titles were relinquished: just as Bearzot’s aging World Champions had appeared sluggish at Mexico ’86, Lippi’s heroes of Berlin failed to ignite South Africa in 2010. But there the comparisons end. The Italian public never warmed to Lippi or his winning team as they had for Bearzot’s Italy twenty-four years earlier. The rakish, fresh-faced calciatori who beat the world’s very best in 1982 seem like a different species to 2006’s squad of professional athletes, with their shaven heads and tattooed torsos, who combated their way to an intense shoot-out victory. Despite the more recent title, Italians still recall 1982 with fondness, but not simply out of nostalgia. They consider the success more real, more human, more Italian. There were no fireworks at the Bernabeu in 1982, no novelty hats, no headbutts: just emotional embraces and azzurro blue jerseys soaked through with sweat and spumante.

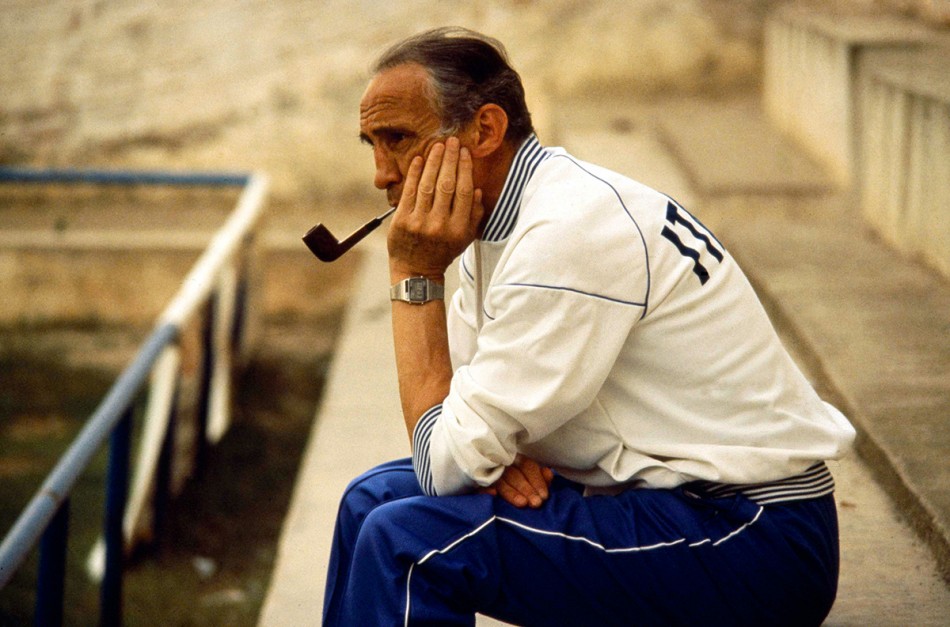

Not long after I moved to Florence I got to know Dott. Fino Fini, Director of the Museo del Calcio at Coverciano (the Italian Federation’s training headquarters). Dott. Fini had been the Italian national team doctor from 1962 to 1982, and the museum was packed with memorabilia from that fertile period. The blue shirts of each player from Bearzot’s winning team were hung in hinged glass frames which swung to reveal the shirt numbers on the other side: 14 Tardelli, 16 Conti, 20 Rossi. In another frame was Bearzot’s entire outfit from that jubilant night in Madrid: grey trousers, blue shirt, navy tie, and the famous blazer, complete with embroidered ITALIA crest. It had always appeared plain white to me on TV, giving its wearer the air of a medical professional, a mediterranean doctor of soccer, but on closer inspection the jacket was made up of narrow navy pinstripes, almost like seersucker. It was a strange feeling to see something in the flesh I’d seen on television a hundred times, like seeing a costume or prop from a favourite movie. Also on display was Bearzot’s trademark pipe, without which he was rarely photographed. “If there was no smoke emanating, that’s when you knew he was a little ticked off,” said Giancarlo Antognoni, who missed out on the 1982 final through injury. Bearzot’s World Cup winners were all quick to recall the human side of il Vecio. “I’d like to remember him sitting on a wall,” said Tardelli. “Smoking his pipe, alone.”

In his later years, Bearzot had become disillusioned with all aspects of the modern game. “I haven’t been to the stadium in a long time,” he revealed a few months before his death. “The stands have become a platform for shouters to hurl the most ferocious insults.” He didn’t much enjoy watching football at home either. “The TV is less likely to make me angry when it’s switched off,” he quipped. His principal complaint arose from a perceived lack of respect among those involved. “It irritates me when former referees insult referees, or when coaches insult other coaches. I’ll never understand those who insult their colleagues.” But Bearzot also expressed concerns over the business of the sport. Speaking of his decision to retire, il Vecio explained, “It appears that money has moved the goalposts. It seems football has become a science, though not an exact one. For me it will always be a game.” Bearzot’s death signals the loss of one of international football’s legendary figures. But perhaps more significantly, it also comes with the undeniable realisation that the game he spoke of is well and truly over.

Enzo Bearzot, 1927-2010