Before the cloud of dust and ash had even reached Brooklyn they were already calling it our generation’s “J.F.K.” We all remember it — where we were, who we were with, what we were doing. I’m not going to tell you my memories of 9/11 because they aren’t probably much different from those of most other people who weren’t in New York that day. Surely to do so would be to weigh in on an already over-saturated topic, to intellectualize other people’s all-too-real tragedy, and to appropriate their daily pain in an empty gesture of solidarity. I’m not an American, I wasn’t in New York ten years ago and I didn’t personally know anybody who died in the attacks. Who the hell am I to get in the way of those who are, were, and did?

I was hesitant to write about 9/11 at all until a New Yorker friend convinced me otherwise. She talked about the “ownership” of 9/11, her view being that it belongs to us all (unlike 9/12, which belongs only to New York). Indeed, as much as those events were an attack on the freedom of the Western world at large, it was New York that had to grapple in the aftermath of a very real disaster. Yet while the city was distracted, its back turned, its energies drained and emotions exhausted, somehow “9/11” was swept upon — by politicians, media, or simply the circumstances of an imminent global threat — and rebranded as an American tragedy. It was a subtle shift but one which opened up the city to the rest of the country, welcoming swathes of out-of-towners who’d previously avoided New York at all costs (“too dirty, too dangerous”), and perhaps consequently setting in motion Manhattan’s rapid and alarming suburbanization.

I know more than one American who has admitted to me that they didn’t know what the World Trade Center was on 9/10. Today several of my Facebook friends — many of whom have never been to New York — have updated their statuses and changed their profile pictures accordingly to reflect the supposed mood of the city. I even read about a guy who remained incredulous last Friday when a colleague wished him a “Happy 9/11”. Given this, plus the slew of discussions and hollow sentiments gushing our way this anniversary week, I wish more people were as reluctant to share thoughts on 9/11 as I am.

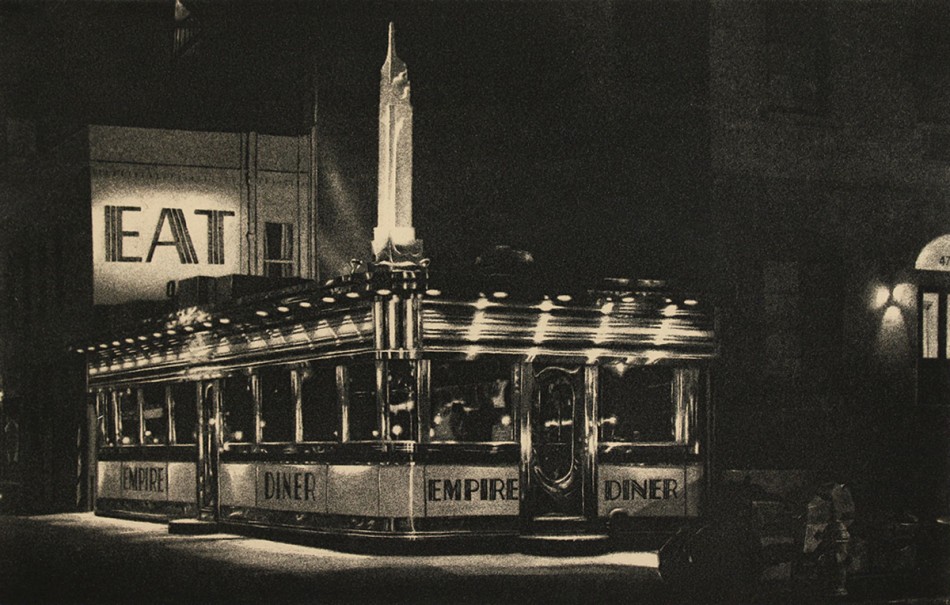

Ironically, while the rest of America has embraced New York in its visitor-friendly post-9/11 guise, so New Yorkers increasingly yearn for what has been lost over the last decade. I’m always surprised just to what extent the city I wake up to in 2011 differs from the New York that has always existed in my head, where, along with DON’T WALK/WALK lights and Checker cabs, the Twin Towers are still very much there.

I visited the Twin Towers once when they really were still there, and rode the startlingly fast elevator to the top floors and observation deck, where I walked about for roughly a half-hour under the hazy July sun, marveling at the view and taking photos with my Pentax K-1000. I have one super wide montage (which I pieced together once my photos had been developed) looking north where you can see the curvature of the earth. I took another great shot looking directly across at the other tower, and I remember being able to see the Colgate HQ across the river (the giant clock is still there). NY1 called it the hottest July 5th on record at the time, and you couldn’t make out much beyond Central Park because of the haze. My mum went during a crisp November a few years earlier — in her photos you can probably see Connecticut. There was a point near the gift shop and restaurant where you could step down to the windows and put your toes against glass. It was pretty scary (in a fun sort of way) at the time; the memory became terrifying a few years later.

After moving to New York it never occurred to me to visit what had by then become habitually referred to as “Ground Zero”. I don’t know if having lost loved ones would be greater incentive to visit or a big reason to stay away, but I find it odd that people travel across America to visit the former site of the World Trade Center and pose for photos in front of what has begun only recently to resemble something other than a building site. (It’s still the only “tourist attraction” I can think of in which people come to see something that isn’t there, rather than something that is.) But I’m sure they all leave with a commemorative fridge magnet to take home.

Having said that, I think after all the speculation the new memorial site is far more perfect than anything I could have imagined. Those two square pools are a powerful sight. Maybe it’s naive to hope that the re-opening of the site will act as a sort of closure for the city, and that vast space as it develops can finally return to being a living, breathing part of downtown Manhattan. But it will probably be a long while before I go down there.

I certainly would never have dreamed of going downtown today. Instead I stayed at home, curled up on the sofa with a cup of coffee and a bumper edition of Sunday’s Times (which I’d bought on Saturday night). I got seriously choked up during the TV memorial service when kids barely old enough to remember their dads started to cry as they read out their names. The list was especially moving when they got to the most common last names, like Smith, and it began to read like a phone book.

A decade of cheap tourism, internet theorists, airport security lines, late-nite terrorism gags and numbing scenes of war on the nightly news has made it easy to forget that few people in this city weren’t directly affected by what happened on 9/11. Ten years is nothing, and when I speak with New Yorkers — or anyone for that matter — I never bring it up. And despite everyone’s desire to move on the subject should continue to be treated with caution and respect, a tough task for many given the current choice of platforms encouraging extreme opinions and knee-jerk reactions.

Too many New Yorkers wear the fact like a badge of honor. Let’s always try and remember that some have earned theirs.