When I first visited Florence, in the summer of 1988, I was surprised to find that the city’s most famous square, Piazza della Signoria, had been reduced to little more than a gigantic hole in the ground. The purpose of this excavation was to unearth some of the myriad relics that lay below the surface of the piazza, but the project had become open-ended when archeologists discovered Roman baths, three churches, plus towers, streets, walls and cemeteries hidden beneath the city, all dating back centuries. Eventually a perspex floor was laid over their findings allowing pedestrians the chance to gaze into this forgotten world. The fact that such endless historical bounty sits just feet below one of the world’s most visited cities is a major reason why Florence remains the only major Italian city without a modern metro.

Years later, while living in Florence, I often recalled my first visit and sometimes wondered what was below the streets I now walked on daily. Which in turn led me to often ponder how different Florence might have been had it gone ahead with any of the several suggestions for an underground rail network put forward over the years. In 2010 Florence restored its tram service which had been closed down since 1958. The first line opened connects the suburb of Scandicci with the city’s main railway station, Stazione Santa Maria Novella. Work has since begun (belatedly) on one of three more projected lines, parts of which may be underground, leading some residents to opine that a genuine metro would have been a smarter long-term solution.

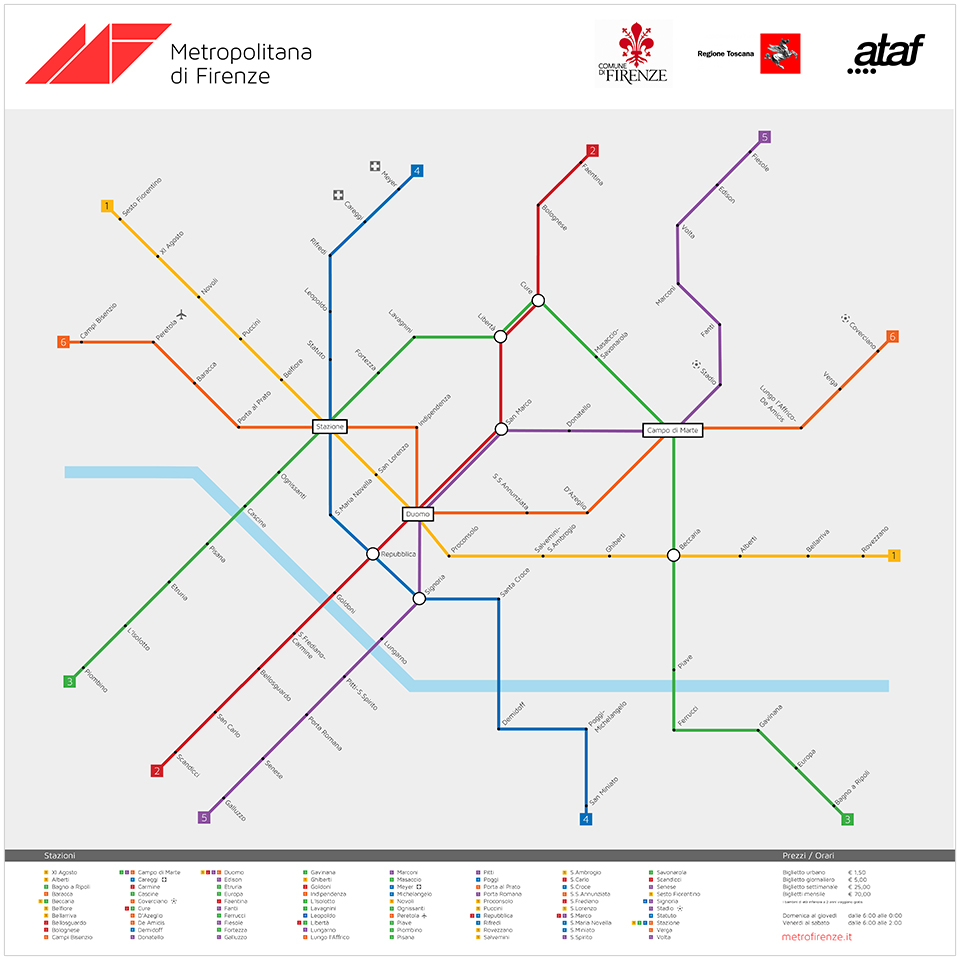

With this in mind, I finally decided to create my own hypothetical Metropolitana di Firenze, a project that has taken the best part of a year and forced me to branch outside the safe confines of the aesthetics of design and into the complex realm of public transport and urban planning. The first and most daunting task was to plot the network itself, something that posed a considerable challenge, and I soon realized how an inside knowledge of the working city is essential in order to even begin such an undertaking. I began by listing the city’s major points and drawing a rough map from memory, imagining the most useful locations for stations and the distances between them. The hardest part was plotting the actual train routes, deciding where they should start and finish without doubling up on other lines. Since Florence’s centro storico is relatively compact, I made sure each line connected an area of the city’s outskirts with its center; the same lines frequently interconnect with one another allowing passengers the flexibility to divert their own route. In my enthusiasm to cater to all residents in every part of town, I was ultimately able to service the whole city more than adequately with six lines, although Milan (3), Rome (2) and Naples (2) seem to get by with half as many.

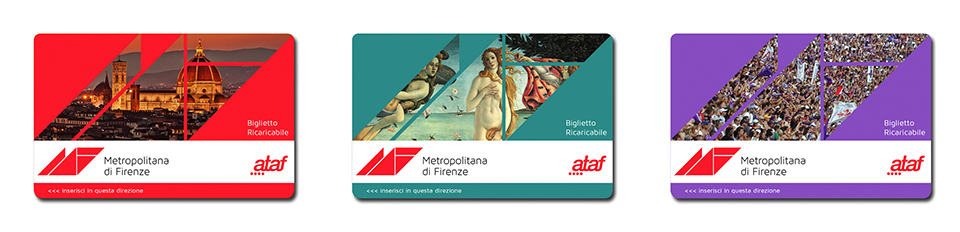

With the possible exception of the London Underground, public transport logos are rarely memorable, which is why I deliberately kept this one fairly low-key. I wanted it to look like something that could have existed for several years without ever being considered for an update. That being said I wanted it to evoke aspects of Italian graphic design. The use of triangular shapes is a subtle nod to the Futurist movement which, in addition to being preoccupied with speed and technological advancement, is inexorably linked to Florence. I also chose a typeface that was clear and modern but not without personality. The logo is echoed throughout all of the metro’s printed collateral, creating a geometric window device which can be updated regularly to feature different images of the city. As is the norm for modern underground networks, tickets are swiped for entry and are available for a single-trip (€1.50), or as daily (€5), weekly (€25) or monthly (€70) cards.

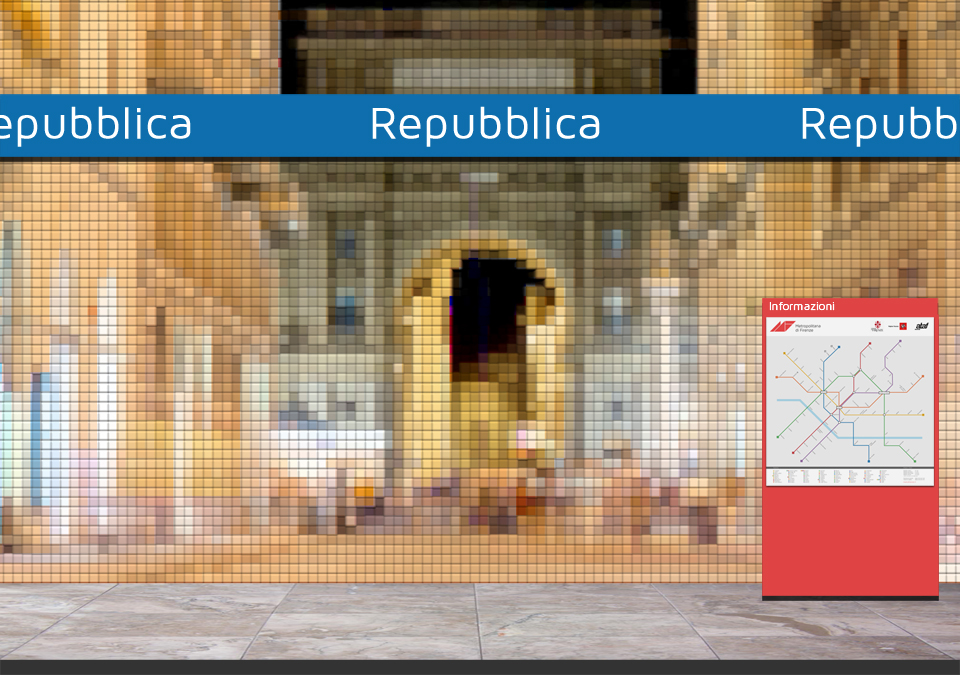

The station platforms are highlighted with color-coded signage corresponding to the relevant line, while large wall-to-wall LCD screens project live footage of the street directly above, creating an ever-changing mural of light. Another twenty-first century innovation is the smartphone app, which allows travelers to plan their journey and learn the quickest route to their final destination. As I mentioned already, this project is solely hypothetical and admittedly unrealistic: the construction work alone for such a dense network would cause decades of disruption to thousands of people daily. I certainly do not expect Matteo Renzi to jump on the idea with any urgency. Rather, it is simply a self-assigned exercise to finally realize a concept that’s been floating around my head for about twenty-five years.