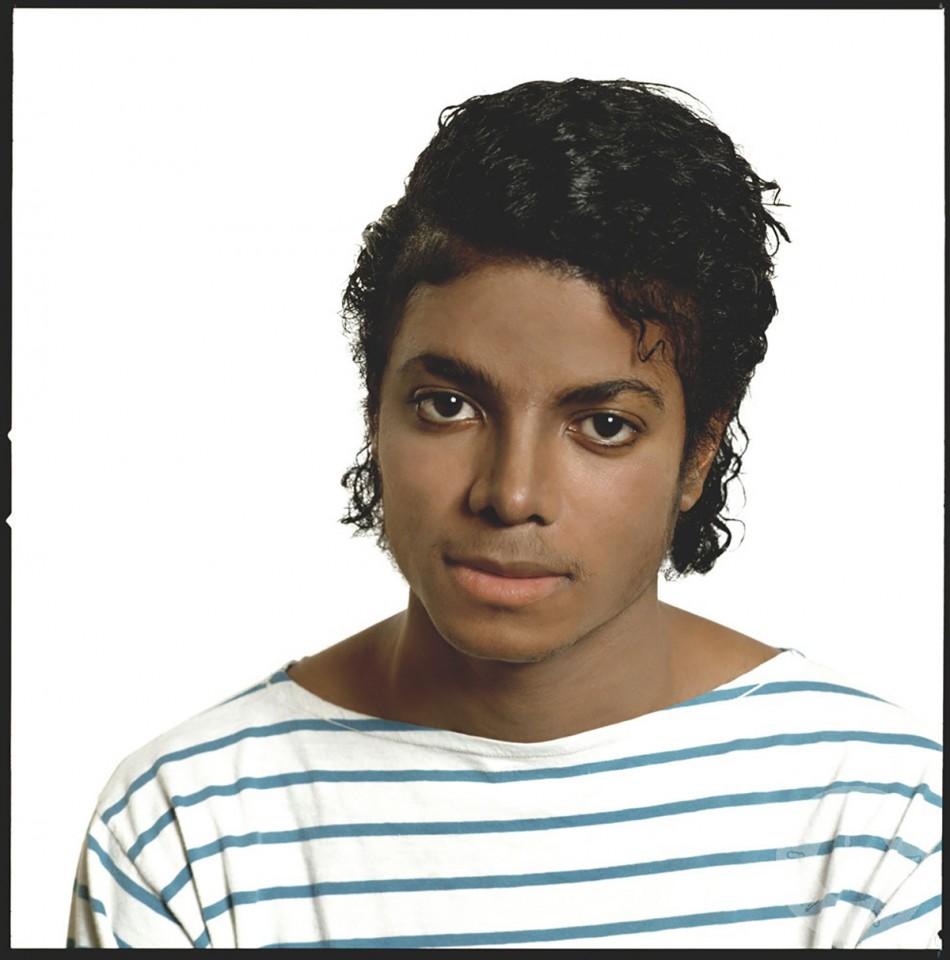

THE WHOLE WORLD’S GONE OFF THE WALL. So proclaimed the promotional posters hailing the release of Michael Jackson’s solo album Off The Wall in 1979. Exactly thirty years later, the phrase seemed equally apt on a warm June evening, as news of Jackson’s hospitalization, shortly followed by the confirmation of his death at the age of fifty, began filtering through the early twilight. Sidewalks quickly swelled with people leaving work as passing car radios alternately blasted news updates and Jackson’s greatest hits. Cellphones lost reception. Internet browsers became sluggish. Twitter crashed completely. It was one of those rare moments in which suddenly everybody everywhere was consumed by a common story.

Listening to the Michael Jackson playlists being spun on every radio station that night, I was struck by the sheer quality — and number — of those hits. Jackson’s talent as a vocalist and songwriter was often overlooked in favour of the undeniable influence he commanded over pop music’s increasingly visual world. It had been a long time since I’d heard a lot of those songs outside of the context of a music video. Television also has a habit of abandoning the schedule for international incidents and now, even several days later, the pop icon’s videos and performances continue to dominate the airwaves in one continuous loop.

Though the circumstances are tragic, this unexpected revisiting of Jackson’s material has actually been a rare treat, and while not quite invoking a reappraisal of his talents, it has certainly acted as a reminder as to what made the man so special in the first place. Whether scuffling in an epic street ballet or gliding across the stage in a sequined cardigan, the overall affect of this impromptu musical retrospective is both moving and awe-inspiring: what a talent, what a waste. For the last fifteen years of his life, Jackson had primarily existed in the public conscience as a celebrity of former greatness who had been reduced to playing the role of eccentric Hollywood recluse, responsible for a catalogue of tabloid fodder and practically no musical output.

For those who had witnessed his transformation from precocious stage presence turned prince of the dancefloor to multi-million dollar intergalactic megastar, it was hard to watch the King of Pop give up his title so easily. When John Lennon was suddenly murdered at the age of 40, fans were left to wonder what music the former Beatle would never make, a sensation which only grew as the ’80s and ’90s progressed. Like Jackson, Lennon was in the throes of a comeback at the time of his death in 1980, having just released Double Fantasy, his first LP of new material in five years. But as Jackson prepared to embark on his This Is It tour, an epic series of fifty concerts which will never happen, his death frustrates in a bizarre reversal. Just think of the music he might already have made, had his last decade on earth not been taken up by drawn-out legal battles and increasingly odd public behaviour, not to mention his alarming physical transformation and subsequent declining health.

Jackson was hardly a prolific recording artist, even during his peak. Fellow ’80s icon Prince (who is the same age as Jackson) has released thirty official albums in as many years (plus countless bootlegs and unreleased tracks). Jackson in contrast made just ten solo albums between 1972 and 2001. While Off The Wall, Thriller and Bad — the trilogy of best-selling solo records Jackson produced with Quincy Jones in an eight-year period — still sound as fresh today as they did when first released, his work either side of this holy trinity is at best patchy, at worst irrelevant. Perhaps the greatest testament to Jackson’s impact is that such unprecedented fame, universal recognition and out-and-out notoriety was achieved on the back of only three classic albums. This perhaps reinforces the notion that Jackson’s legacy is as much visual as it is musical.

What happened after that is one of the great pop-culture mysteries of our time, one which transfixed the public as much as Jackson’s talent had decades earlier. The music — what little fresh material there was — had become a secondary feature, and by the late ’90s Jackson’s transformation was almost complete. In the eyes of a huge public majority, he was now a has-been, a freak, and for some, a criminal. Even his most ardent fans asked — and still ask — how this could be the same man they’d fallen in love with?

Perversely, though neither sought after nor lucrative, this new kind of media attention became something of a second career for Jackson. Except where once he had beamed at us from the cover of a glossy LP, his face was now more commonly disguised behind dark glasses and a surgical mask, splashed across the tatty pages of every drugstore gossip rag.

In this undeniably sad moment in popular culture, many of those who knew Jackson, professionally and personally, have done their best to dispel the controversy that plagued him, presenting the man as the smart, warm, truly gifted human being the rest of us would prefer to think of him as. For a person who spent his final years associated almost solely with acts of weirdness it’s particularly touching to hear Jackson’s colleagues and friends recall the star’s rare moments away from the spotlight. Quincy Jones spotting the young Michael backstage eating a sandwich; Brooke Shields poking fun at his famous rhinestone glove; Bad tour backing singer Sheryl Crow staying up with Jackson in his Tokyo hotel room to watch the western Shane.

In 1994 Jackson married Lisa Marie Presley, in an unexpected union of pop dynasties. Though they divorced less than two years later, it now appears to have been his most orthodox adult relationship. The day after Jackson’s death, Presley revealed how her then-husband had once confessed to her his own fears of ending up like her father, who for much of the ’70s was a bloated, grotesque version of his former self. Ultimately, in a twisted reversal of Elvis’ gross demise, Jackson simply withered away, and, as befits modern pop icons, before our very eyes. The King is dead — this time they really mean it.

Michael Joseph Jackson, August 29, 1958 – June 25, 2009